In this year of remembrance of the outbreak of the First World War, no more profound symbol of the carnage and valour can be found than in the cemeteries, created and still maintained by the Commonwealth (formerly Imperial) War Graves Commission.

Although monuments to fallen heroes have existed since ancient times, never before had all the military casualties of war been commemorated in such a formal and physically defined way. The commission cemeteries express a concept of remembrance and ideals that continues in perpetuity, because of a timely commitment, just under a century ago, that we would “never forget.”

A hundred years on, today’s visitors to these scrupulously maintained cemeteries still find solace in the places where soldiers gave their lives. They are found all around the world from India to Gaza to Hong Kong and include all theatres of both the First and Second World Wars, wherever these forces fought, but particularly in France and the blood-soaked fields of Flanders. Even for visitors with no direct relationship to the fallen, the arc of connection stretches down through generations, a permanent remembrance in a world of continuing chaotic change.

It was the sheer numbers of dead in the First World War that gave rise to the idea. Wellington’s battle at Waterloo, fought nearby just a hundred years earlier, had created an estimated 7,000 Anglo-allied dead and missing. Most of these, apart from the rescued bodies of nobility, were buried in anonymous pit graves near the battlefield, causing the writer Thackeray to rail on behalf of the fallen: “shovelled into a hole … and so forgotten.”

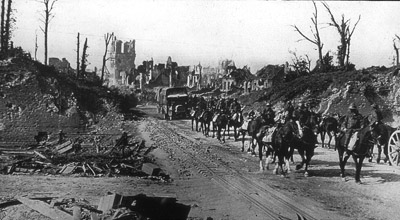

Photo is courtesy of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

By contrast, at the end of the first year of the 1914 war alone, more than 16,200 officers and men had already been killed, 48,000 had been wounded and nearly 17,000 were missing. Before it was over, there would be more than a million lost from the British allied armies alone.

In the early months of the war, England’s Royal Automobile Club encouraged its members to send their cars to France to serve as ambulances. These semi-amateur volunteer attempts to help rescue the wounded or dead from the battlefield with a handful of vehicles were soon overrun, as were early efforts to ensure that graves were marked and identified. Matters were hampered by the constantly shifting battle lines on the field and the industrial scale of death that had never been seen before in history. It was largely through the leadership of one man, Fabian Ware, that this unprecedented devastation was formally acknowledged and organized. A thoughtful new book, Empires of the Dead: How One Man’s Vision Led to the Creation of WWI’s War Graves by Scottish writer David Crane, documents the life and work of the British-born Ware, who had come to France to run the Mobile Unit of civilian vehicles aimed at finding casualties. He ended as the architect of what we know today as the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Ware grew up influenced by the faith of dissenters such as the Plymouth Brethren, a dominant religious force near his birthplace of Clifton near Bristol. He was an ex-journalist, a product of the Edwardian era, imbued with notions of empire. Its strength, in his mind, lay in its collectivity (Crane calls him “a social radical in conservative clothing”). The cause he took up soon after he came to France would become his life’s work. Those who eventually would join and support him included not only Britishers, such as the writer Rudyard Kipling, the trade union leader Herbert Gosling and Winston Churchill, but representatives from Britain’s dominions and colonies. In Canada, Ontario-born Colonel Henry Campbell Osborne (whose modest fortune came through a connection to the Massey-Harris farm implement company and whose duties had kept him out of the trenches) was appointed the first secretary of the Canadian Agency of the commission.

Although the idea of empire has been largely discredited in the modern age, Ware embodied the best of that idea’s values. He embraced tradition but also modern notions of equality and non-discrimination that came directly out of that horrific era. Ware believed in the individual but even more in the greater collectivity based on the ties that stretched across the empire and the ability of those collective ties to produce something memorable and worthwhile.

Taking, as Crane’s book puts it, “a protective interest in the graves of the dead,” Ware started off in 1914 with the ad hoc mobile unit of make-shift ambulances. With time, Ware focused more systematically on keeping track of the graves of the fallen. While others, such as the Paris-based British Red Cross, were engaged in a similar endeavour, their work was more often in response to specific requests to try to find usually notable individuals. None had the consistent and thorough approach of Ware’s small unit, which focused on marking all the graves they could locate and ensuring that the fallen were identified. Simple wooden crosses, tarred at the base and where possible carefully inscribed, were the first tombstones, and sometimes the dead person’s identity was even contained on a scrap of paper inside a bottle buried upside down at the gravesite. As time went on, Ware helped in the development of identity discs designed to be indestructible, although even these could be lost. Initially his group had no official status. But as casualties mounted it was decided to put things on a more formal footing. The British army was acutely aware, as noted in Philip Longworth’s The Unending Vigil: The History of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, of “the chaos and distress caused by the neglect of graves in the Boer War.”

By the summer of 1915, Ware and his team were given full control over the project. The unit operated under the title of the Graves Registration Commission, its work now fully supported by the British Army. Longworth notes that even General Haig, leader of the British Expeditionary Force, who was to send so many men to their deaths, gave Ware’s work official recognition, although he reported to the British War Office that “it is fully recognised that the work of the organisation is of purely sentimental value … It does not directly contribute to the successful termination of the war.”

In May 1917 Ware was put in charge of the Imperial War Graves Commission, newly created by Royal Charter. Its job was to provide permanent graves for the dead and commemoration for the missing. By the end of the First World War, this meant full and sole responsibility for the handling of the fallen and the memorials and cemeteries that would mark what was now the more than a million lost British subjects. It was a Herculean task. Another 600,000 graves were to be added at the end of the Second World War under the remit that the commission had been given “for the graves and remembrance of all those, anywhere, who died on active service.”

The commission’s work was driven by three key principles. The first was to end the class discrimination that had led in the past to recognition for the great and the wealthy but little for the common soldier, now numbering hundreds of thousands from all ranks of society. It was decided that, for the first time in known warfare, officers and men would be treated exactly alike in death with no special consideration based on military rank or social status. This meant all ranks would lie beside one another in identical graves or be named in the same manner on the commemorative plaques to the missing. Nor would there be monuments raised to individual heroes, at least not under the commission’s aegis.

With the end of the war, Longworth recounts, army orders against the exhumation and repatriation of bodies lapsed. The Americans had promised to repatriate all their dead, but their casualties were relatively few. The British government had made no such commitment. Ware and his commissioners had to move fast to decide what their policy would be on this second crucial question. They agreed that the bodies of the dead were not to be repatriated but buried and commemorated as close as possible to where they had fallen. Longworth notes that “the Commissioners judged that ‘to allow the removal by a few individuals (of necessity only those who could afford the cost) would be contrary to the principle of equality of treatment … [and] … a higher ideal than that of private burial at home is embodied in these war cemeteries in foreign lands’.” Those who had fought and died together should remain together in their last resting place. No other principle was to cause more anguish or protest among those who had the means and connections to try and retrieve their dead. Some, a few, succeeded, spiriting the corpses of their loved ones away, to be buried in family plots, in familiar cemeteries at home. These included a celebrated Canadian case in which a Toronto mother, Anna Durie, after several unsuccessful attempts and likely against her dead son’s wishes (he was killed at Passchendaele) retrieved his body from a War Graves cemetery and brought it back to Canada in 1925, after eight years of effort. A modest death notice in the Toronto newspapers marked his quiet reinternment in Toronto’s St. James Cemetery. A thriving illicit but lucrative trade had grown up around the battlefields to assist these grisly attempts. But these activities were vigorously resisted and condemned by the authorities.

In Canada, the non-repatriation policy created many anguished letters to the Canadian Agency of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in Ottawa, each personally and patiently answered by Osborne, but with no softening in the commission’s position. This issue refused to abate and led in 1920 to a protracted parliamentary debate in Britain. Families opposed to the decision could not understand why those who could find their dead could not bring them home. But the commission’s stand was eventually upheld and the sparring parties decided there should be no divisive vote on an issue so deeply sensitive to all parties. It was a moot point for those families who had no trace, and never would, of the remains of those they loved.

Lastly, recognition for the fallen was to be ensured “in perpetuity,” as indicated in the Royal Charter, a reminder of what really was then thought to be “the war to end all wars.” The commission’s financing was to be permanent, paid by a careful formula based on the number of dead from each country associated with the British empire—Canada’s share, 7.78 percent, was based on its calculated portion of the total war dead, estimated at roughly 65,000 men. This formula with some refinements (Canada’s share today is 10 percent) is a commitment that each government continues to honour and the money is used to fund the commission’s current work. It was and remains an international organization immune to domestic cuts in budgets for veterans or defence affairs.

As one walks the rows of headstones in any one of the commission’s cemeteries today, one cannot help but be inspired by the peace and contemplative tranquility that these places engender. In this regard the aesthetic adopted by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission has a powerful role to play.

When it became clear that the dead were to be grouped into cemeteries large and small throughout the war area, it was Ware who achieved an agreement with the French government that turned over land forever for this purpose. The implementation of the commission’s design meant that “new narratives of nationhood” were being formed as Ware made sure that the wishes of the dominions and colonies (which included Newfoundland) were considered. He also aimed to shift away from hierarchical views of empire, to a collective notion of an “empire of equals.” The planning and execution of his project were exemplary in the impetus for the gradual emergence of the Commonwealth in later decades.

No expense was spared in the creation and maintenance of the cemeteries and monuments, and every effort was made to satisfy religious as well as military sensibilities. The battlefield had, in the words of David Crane, “obliterated not just the individuality of the fighting man but also his very physical integrity.” Now the task was to devise a pastoral world that would restore the essence of the fallen. Ware immediately sounded the arts community for ideas on the treatment of the war graves, engaging among others the services of Edwin Lutyens, Herbert Baker and Reginald Blomfield, leading architects of their day, as well as other prominent figures, including Arthur Hill, the director of the Botanical Gardens at Kew near London, who was already advising on horticultural matters. Hill made a research trip to the battlefields in the spring of 1917 when a profusion of poppies were in full bloom across the French and Belgian countryside. Lutyens, alternatively, visited the areas in the grim grey weeks of November. Both experiences were to infuse the outcome. The dominions wished to use native species to mark their dead, and in this the Canadians were lucky as cedar hedges and maple trees could flourish in the cold climates of both countries.

For Baker, the serenity of a quiet English churchyard was what he had in mind, while for Lutyens something more austere and abstract that would transcend the multiplicity of religions and races involved was central to his vision. (He tried to persuade the archbishop of Canterbury to his view in an encounter at their London club but only succeeded in alarming the Christian prelate with his views.) As in all government-associated artistic projects, a compromise was sought, and Sir Frederic Kenyon, director of the British Museum, made vice-chair of the War Graves Commission in 1917, was brought in to reconcile differences. This led eventually to the placing of both Lutyens’s great Stone of Remembrance as well as a Cross of Sacrifice—Blomfield’s design was endorsed—in all cemeteries, the latter satisfying powerful interests in Britain and elsewhere that the Empire had been, or at least so they thought, primarily Christian. Still, strong efforts were made to recognize the religious precepts of non-Christian combatants. This was also later true for the graves of the Second World War.

The essential restriction—that there should be no difference made between officers and men—remained completely intact. The shape of the headstones, their placing in serried rows, the choice of language to identify and commemorate each soldier were strictly set. There was place for only a short phrase of commemoration by families restricted to no more than four lines and these were subject to the “absolute power of acceptance or rejection by the Commission.” Many were formulaic: “Rest in peace”; “Gone but not forgotten.” But as documented in a recent article by Toronto writer Eric McGeer, it also led to some heart-rending choices: “Death is not a barrier to love, Daddy”; “Sacrificed to the fallacy that only war can end war”; “My heart knoweth its own bitterness, Mother”; “Many died and there was much glory.” Many of the sentiments, McGeer has tabulated, touch on the dreadful contradictions of the war.

All was under the centralized control of the commission, a fact that would create a powerful backlash in later years against what was described as, and indeed was, its authoritarian approach. Still, it was the meticulous work with which it pursued its mission that ensured that not only the half million known dead were recognized, but also that the further half million men who were missing forever would also be acknowledged, on the great monuments of the Menin Gate in Ypres, at Thiepval on the Somme and in other great memorials that were raised under the commission’s mandate. In addition the dominions added their own monuments. Canada raised the magnificent Vimy Memorial at Vimy Ridge near Arras, where Canadians had so distinguished themselves in battle in 1917. The monument was built on land given to Canada by the French and was unveiled in 1936.

Traditions of honesty, simplicity and good design marked the commission’s work from the gravestones themselves to “the dignity of the layout to the beauty of the trees, grass and flowers” that surrounded them. It has been the hallmark of the commission’s work.And the work goes on—newly found dead are still being discovered and recognized, and existing graves and cemeteries remain, as always, to be maintained and rejuvenated, in perpetuity, even though the commission’s responsibility ends with the dead of the Second World War.

Since 1945, our approach to the Canadian fallen—in Korea, in Afghanistan and on peacekeeping duty with the United Nations—has been different. We no longer fight for empire or commonwealth, and recognition of those killed in our wars is now a national responsibility. The reception ceremonies of recent years for the returning dead from the Afghan war have been deeply moving for those able to attend and, without question, have provided solace and honour to the bereaved families. The generic naming of main autoroutes a “Highway of Heroes (or Veterans)” seems an impersonal imitation of a habit initiated south of the border. One-day-only government salutes—recently one occurred to acknowledge our soldiers’ brave service in Afghanistan, and previously one for service in Libya—are set apart from our national day of remembrance marked each year on November 11. None of these official gestures, including the formal establishment of the National Military Cemetery similar to Arlington Cemetery in the United States, on a piece of land at Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa, can instil in the mind of the wider public the same profound peace and permanence that the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries evoke. In the wafting scent of the mature cedar boughs circling the site of “The Brooding Soldier” at St. Julien in Flanders, or in the soaring giant Caribou sculpture at Beaumont-Hamel, which recalls the Newfoundland regiment in the graveyard nearby, annihilated almost to a man on their first encounter with battle, or at any other of the cemeteries or memorials that mark where our people fought and died, therein lies the profound and eloquent memory of who we were then and who we are now.

Sarah Jennings is a political and cultural writer in Ottawa and the author of Art and Politics: The History of the National Arts Centre.