On July 27, 1996, in Atlanta, Donovan Bailey won the Olympic gold medal in the men’s 100 metres, becoming the fastest man in the world. I was six years old and instantly hooked. I looked up at my parents and said, “When I grow up, I’m going to beat him.”

Sitting on our living room floor in Oshawa, I thought there could be nothing better than wearing “Canada” across my chest and representing the entire country. I wanted to know what it felt like to have thousands—if not tens of thousands—of people pulling for me. From that moment, it was my mission to become an Olympian.

I was not destined to be a sprinter, however, and I would never challenge Bailey’s 9.84 seconds. But I did find success in longer races, and in grade 11, my coach suggested I try the steeplechase, an event that traces its roots to horse racing. In the eighteenth century, riders in Ireland would race thoroughbreds from one town’s steeple to the next—jumping over whatever hedges and streams were in between. Today, track athletes cover 3,000 metres, hurdling five ninety-one-centimetre-high barriers each lap, including a water jump, at speeds of twenty-two kilometres an hour (or faster).

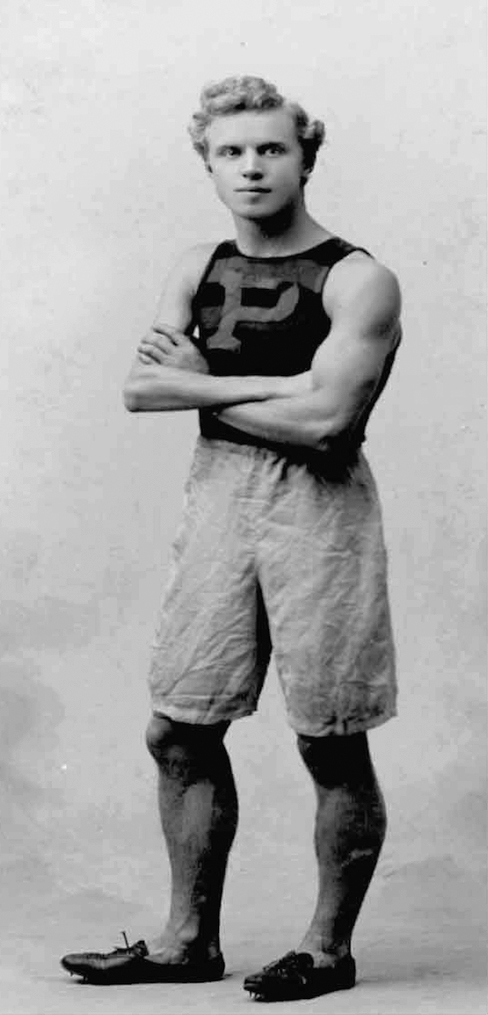

Olympic champion George Washington Orton.

Dundurn

It turned out to be a good suggestion: I quickly established myself as a top steeplechaser and earned a scholarship in the United States, where I won the NCAA Championship twice. I’ve continued competing since graduation; last year, I was the tenth-ranked steepler in the world. And twenty years after I watched Bailey win gold, I confirmed for myself that there’s nothing better than wearing a Canada singlet at the Olympics.

George Washington Orton never had that opportunity, though he won Canada’s first Olympic medals, at the 1900 Paris Games. He was also a steepler—a dominant figure in that event, and others, long before I took to the sport. In many ways, Orton is a founding father of modern track and field, and my predecessor as a Canadian record holder. But, until recently, I had never heard of him.

The sports journalist Mark Hebscher had never heard of Orton either until he was stumped by a trivia question: Who won Canada’s first Olympic gold medal? It turns out the answer was something of a mystery, one that he set out to solve while filming a documentary. In the process, he wrote a book—part whodunit, part whorunit.

George Washington Orton was born in Strathroy, Ontario, on January 10, 1873, not long after Confederation. As a boy, he fell out of a tree and suffered a debilitating blood clot that would affect the use of his right arm for the rest of his life. Doctors assumed he would never walk again, but that wasn’t the case. “At the age of eight,” he said years later, “I seemed to come suddenly out of a dream. From that day onward, I was always wanting to run.” Orton went on to become one of the world’s great middle-distance runners. His record-setting 4:21.8 in the mile, which he ran in Montreal in 1892, stood as a Canadian-soil record for forty-two years. He was also a successful hockey and lacrosse player.

Orton competed while attending the University of Toronto, racing and often beating some of the world’s best milers at Rosedale Field northeast of campus. After he graduated, he received a scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania, where he earned a master’s and a PhD (Orton was fluent in nine languages). As a student and later as a community leader, he helped establish hockey in Philadelphia and within the Ivy League; he advocated for children’s physical education; and he built the Penn Relays into a world-class sporting event. As a coach, he literally wrote the book on interval training. He even came up with the idea of football players wearing numbers on their jerseys to help spectators follow along.

When Orton arrived in Paris for the Games of the Second Olympiad, he didn’t pack a Canada singlet. And though he travelled with an American delegation, he didn’t pack a USA singlet either. It wouldn’t be until 1908 that athletes represented their countries at the Olympics. So it was a P, for the University of Pennsylvania, that Orton wore on a brutally hot afternoon in July, when he took third place in the 400-metre hurdles (Canada’s first Olympic medal) and then came back forty-five minutes later to win in dramatic fashion the 2,500-metre steeplechase (our first Olympic gold). “I was running fourth, and seemed to be out of the race,” he recalled later. “About 300 yards from home, I seemed to realize that I was in the race for which I had come 4,000 miles.”

In the nearly 120 years since Orton’s historic victory, he became little more than a footnote in the annals of Canadian sport, often overlooked entirely. Hebscher details how that history was written, how Orton was forgotten by many (but remembered fondly by others), and how it wasn’t until the 1970s that the International Olympic Committee added Orton’s medals to Canada’s all-time tally.

As can be the case with a whodunit, The Greatest Athlete (You’ve Never Heard of) is overly discursive and the prose is, at times, cringeworthy. Hebscher goes down too many rabbit holes, shares too many anecdotes from other sports, and searches in vain for Orton’s Olympic medals, even as he concedes that not all athletes received them in 1900 — the Paris Games being a rather unorganized, almost informal affair, quite overshadowed by the Exposition Universelle across town. Despite these and other distractions, Hebscher has resuscitated an important figure, one whose successes on the track and off profoundly shaped modern sport in North America.

Why did Orton represent Penn instead of the University of Toronto at the Paris Games? Why did Canadian sportswriters come to think of him as an American, before forgetting him entirely? Why do young Canadian track athletes never hear his name spoken alongside the likes of Donovan Bailey, Harry Jerome, Bruce Kidd, and Sylvia Ruegger? Part of the answer has to do with the role amateurism played in highly conservative Toronto at the turn of the twentieth century. Good society looked down on any hint of professionalism. Athletes were not to earn money from sport. In many cases, athletes were expected to foot all the costs of travel and accommodations. Classism kept many from competing at all.

For Orton, patriotism had little to do with competition. The University of Pennsylvania offered him the financial support he needed to race at a time when none in Canada would. Of course, unless you’re playing baseball, basketball, football, or hockey, it can still be hard to cover all your costs as a professional athlete. And while Orton never forgot Canada or his alma mater in Toronto, some Canadians questioned his loyalties. Others just stopped remembering.

Now that I know Orton’s story, I won’t forget it. When I toe the line in Doha this fall, for my fifth World Championships, I will once again wear “Canada” on my chest. But this time I will remember Orton. I will remember the guts and the fortitude he showed while competing on the world stage. I will remember that he was, and remains, one of the greats. And I will remember that he was one of ours.

Matt Hughes is the Canadian record holder in the 3,000-metre steeplechase.