Brooke Jeffrey has written a solid account of the Liberal Party of Canada from 1984 to 2008. Smoothly narrated, rich with detail and objective in tone, Divided Loyalties: The Liberal Party of Canada, 1984–2008 is a worthy addition to the shelf of Canadian politics. Present-day academics and future historians will be grateful for the wealth of material that Jeffrey has woven together from almost six dozen interviews, scores of confidential documents and countless media reports, although the general reader might find more than 600 pages rather a long march.

While full of triumph and defeat, of intrigue and betrayal, Divided Loyalties is less a drama than the stuff of drama, like one of those chronicles that inspired Shakespeare to write his history plays. It lacks the muse of storytelling. There are few insights into the players, no passionate judgements pro or con, and remarkably little scoop for an insider’s version of events. (Jeffrey, currently director of the Master in Public Policy and Public Administration program at Concordia University, served as director of the Liberal Caucus Research Bureau from 1984 to 1990 and remains an occasional advisor.) But, to be fair, drama is not her purpose.

Her commendable intent is to focus on policy and the mechanics of a modern political organization. She is not much interested, despite positioning herself as a left-of-centre Liberal partisan, in throwing rocks at the Tories or their kindred spirits on her party’s right wing. Instead, she marshals her evidence with scrupulous neutrality in support of a single thesis, which she states early and more than once.

“As this book demonstrates,” Jeffrey declares, “Prime Minister [Brian] Mulroney’s introduction of the Meech Lake Accord triggered a chain of events that contributed directly to the party’s current state of disunity, creating an entirely new and deep-rooted division among Liberals about the nature of Canadian federalism. Indeed, over the past twenty-five years the federalist cleavage has become a dominant if largely unrecognized characteristic of the Liberal Party, affecting both its leadership and its rank-and-file members. It is now arguably as important as the traditional left-right cleavage between ‘social’ and ‘business’ Liberals.”

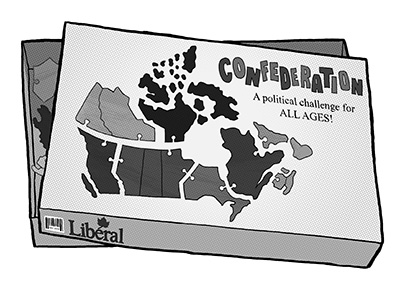

Eric Uhlich

Jeffrey is undoubtedly right to call attention to the existence of this centralist-decentralist cleavage within the Liberal Party of Canada. The problem is, it is a large, elusive whale of an idea, breaching impressively from time to time, then sinking out of sight. Her thesis would have been better served,

I think, if her book had gone deeper rather than so broad.

It is always tricky for an intellectual to try to pin a thesis on something as slippery as the Liberal Party of Canada. It prides itself, after all, on being pragmatic rather than ideological, a big and open tent. The pursuit of victory, not the purity of vision, has been its trademark. And, just as Liberals have been on both sides of the business-social cleavage, so they have been on both sides of the centralist-decentralist cleavage.

Pierre Trudeau may be pegged as a centralist, for example, but Canada became the most decentralized federation in the world during his regime. By his own admission, he almost “gave away the store” to the provinces during the constitutional talks in the 1970s. Jean Chrétien, presumably another centralist, supported the Charlottetown Accord when Trudeau did not, weakened national programs with the Canada Health and Social Transfer and Social Union Framework Agreement, and recognized Quebec as a distinct society in a parliamentary resolution. Conversely, on the so-called decentralist side, John Turner took on most of the provincial governments, as well as Bay Street, in his fight against Mulroney’s free trade deal with the United States, and Paul Martin Jr. went to bat for the healthcare system and a national childcare program.

It is always tricky for an intellectual to try to pin a thesis on something as slippery as the Liberal Party of Canada.

Moreover, by its own evidence, Divided Loyalties suggests that the major division contributing to the party’s downfall had very little to do with clashes over policy. Chrétien usually gave way to Martin on the business agenda; Martin usually gave way to Chrétien on the national unity agenda. What drove them apart was the raw, ruthless ambition of Martin’s inner circle, the Board, a Toronto-based gang that wanted to wrest control of the party, of the government and of the rewards of high office from the Montreal-based gang, for no other apparent reason (as Jeffrey’s narrative makes perfectly clear) than to get into the winner’s circle before their champing-at-the-bit filly turned into the old grey mare.

In this regard, although it is noble of Jeffrey to wish to shift the discussion away from the media’s fixation on personality, it is fair to wonder whether the Liberals would be in such a deep ditch if the social-business, centralist-decentralist cleavages had not been exacerbated by the heavy–handedness of the closed shop around Paul Martin, many of whom (as Jeffrey points out) had also been in John Turner’s camp until they turned on him for being such a loser. Divided Loyalties documents a truly unbelievable litany of meanness, pettiness, arrogance, indecisiveness and plain incompetence, made all the more damning by Jeffrey’s even tone and impeccable sources.

“Unkind critics call them assassins,” Tom Kent, the brilliant Liberal thinker, is quoted as saying. “That’s certainly an exaggeration, I’m sure. But they are essentially organizers, promoters, spin doctors—not policymakers.”

These quibbles are not to reject Jeffrey’s thesis, but rather to try to hone it. She is right, I believe, when she argues that “the divisions in the party have not been resolved and continue to plague rebuilding efforts.” But resolving them requires a more complete examination of the federalist cleavage than the one offered in Divided Loyalties.

What confuses matters is Jeffrey’s puzzling emphasis on the Meech Lake Accord, the constitutional deal struck by Brian Mulroney and the ten provincial premiers in 1987. The reason for this may be no more complicated than the fact that she did not get to the party until 1984, or could not bring herself to make her long book much, much longer. But Meech Lake was merely a symptom, not the cause, of what ails the Liberal Party of Canada today.

In fact, the first third of Divided Loyalties has John Turner returning to federal politics in 1984, after a decade in self-imposed exile on Bay Street, determined to undo Trudeau’s federalist vision as well as Trudeau’s interventionist policies, both of which continued to be most prominently represented in the party by Chrétien. Already, as Jeffrey notes, “policies relating to federalism had come to be seen as more important to many Liberals than the traditional left-right struggle between ‘social’ and ‘business’ Liberals.” And yet the book offers no backstory to explain how that came to be.

Surely, the seminal events that changed the course of Canadian history took place 25 years earlier, with the rise of Quebec nationalism (in which the French-Canadian people became identified with the province’s territory) and the birth of a separatist party under René Lévesque. Canadians were forced to confront the very real possibility of the break-up of their country—none more so than the federal Liberal Party, which was in power for most of the 1960s.

Its leader a former diplomat, its Quebec caucus weakened by scandal, its policy wonks moved by a sense of justice or of guilt, the party initially responded to the increasing demands of the government of Quebec with overtures of conciliation and appeasement. It turned away from the centralizing thrust of the 1940s and ’50s toward fiscal devolution and shared-cost programs. It tiptoed toward a special status for Quebec, two nations and asymmetrical federalism.

“By enforcing centralism perhaps acceptable to some provinces but not to Quebec,” Lester Pearson wrote in his memoirs, “and by insisting that Quebec must be like the others, we could destroy Canada. This became my doctrine of federalism.” And yet the nationalist tide continued to rise.

The arrival on the scene of Pierre Elliott Trudeau changed the game. Trudeau, who had spent the 1950s arguing against the federal government’s aggressive intrusions into provincial jurisdiction, now feared that the Liberals’ strategic response was actually abetting Quebec nationalism, while at the same time crippling Ottawa’s ability to manage the national economy, introduce national programs and regulate national commerce.

Special status, by whatever name, was but a gradual path to complete independence, in Trudeau’s opinion. Quebec already had enough power and money under the BNA Act to achieve its social and economic goals. Above all, the Quebec government wasn’t the only defender of French Canada’s language, culture and interests. So was the federal government, not least because it could also speak for French Canadians beyond the borders of Quebec.

Moreover, by ascending to power on a wave of popular mania rather than through the regular party channels, Trudeau and his cadre of proactive francophone Quebecers in effect stole the Liberal Party from the Old Guard, who had grown accustomed to running things from the backrooms of Toronto. The leader now had a direct relationship with the masses that bypassed the entrenched elites.

The core of Trudeau’s vision was less about centralization than about counterweights. He saw Canada as one people, made up of individual citizens freely bound by common institutions, equal opportunities, shared values, official bilingualism and a sense of patriotism. And it was the task of the federal parliament, as the sole representative of all Canadians, to foster national unity and defend the national interest against the centrifugal pressures of ten strong provincial governments and a strong private sector.

“That is the enemy within,” Trudeau declared in an historic speech that should have been cited in this book, “when loyalties are no longer to the whole but there is a conflict in loyalties; when we seek protection of our wealth, our rights or our language not in the whole country but in a region or a province.”

Trudeau’s years in power proved immensely controversial. Two oil crises, inflation, unemployment and deficits befell the economy. The victory of the Parti Québécois in 1976 shook the country to its foundations. The federal Liberals alienated Western Canada with their language reforms and the National Energy Program. The anglophone premiers took a page from Lévesque’s book and began demanding more money and power for their own provinces. The mass party of engaged citizens that Trudeau had dreamed of failed to congeal.

Nevertheless, between 1968 and 1984, Pierre Trudeau won four elections out of five, captured almost every seat in Quebec, beat the separatists in their 1980 referendum and entrenched the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the constitution. By the time of his retirement, the will of federal Liberals—and most Canadians—had been forged by the traumatic battles against Quebec separatism and the constitutional wars against the Gang of Eight premiers. (Jeffrey fails to elaborate on the fact that the Tories and the NDP had been torn apart by the same federalist cleavage.) Liberals had weathered the greatest crisis Canada had ever faced, and won by dint of their courage, conviction and commitment to change.

All this is an oft-told tale, but one worth repeating since it does not appear anywhere in Divided Loyalties. Without it, one has difficulty understanding how two veteran Liberals with the qualities of John Turner and Paul Martin could have screwed up so royally.

As Jeffrey demonstrates, both leaders made the same fundamental mistakes. They misread their control of the party apparatus and their (temporary) popularity in the polls as support for their personal animosity toward Pierre Trudeau and Jean Chrétien. They distanced themselves from Trudeau and Chrétien’s vision of Canada, even when that meant disowning success and trashing experience. They sought to appease the soft nationalists in Quebec, the anti-Ottawa sentiment in Western Canada and the big money on Bay Street. (Although Jeffrey is correct in noting a difference between right-wing Liberals and decentralists, the exceptions tend to prove the general rule that the business community and its political minions favour provincial rights. It is usually easier to pocket a premier than a prime minister, often profitable to play one jurisdiction against another and generally advantageous to hamstring the power of an activist national government.)

Like Joe Clark and Brian Mulroney, who tried to transform the Progressive Conservatives into Pearsonian Liberals until the unstable compound blew up in their faces, Turner and Martin wanted to take Canada back to the mythic days of elite accommodation. But all four prime ministers learned that there was no going back. Each took what seemed the easy road to sure-fire victory, and it led their parties to stunning defeat. Quebec nationalism was too potent, the provinces too feisty, the West too rich, the business community too greedy and the people too empowered for a Canadian prime minister to be able to manage the country through an old boys’ network anymore.

In startling contrast, Jean Chrétien won three majorities in a row, transformed a $42 billion deficit into a string of budget surpluses without uprisings in the streets, passed the Clarity Act and beat the Bloc Québécois in popular vote in the 2000 election, not least by maintaining his connection to the Canadian people and yelling at the end of every speech “Vive le Canada!”

Brooke Jeffrey’s chapters on Chrétien’s ten years in office may be the much-delayed start to a serious analysis that actually tries to get beyond scandals, luck and his populist image. And she is clearly on to something important when she surveys the current crop of devolutionists in all parties in Ottawa and, rather than despairing for the future of the Liberal Party of Canada, sees opportunity.

“There can be little doubt the party will continue to have difficulty differentiating itself from its opponents if it strays too far from its traditional place on the federalist axis,” she writes. “Conversely, a return to that approach would likely ensure its status as the party most able to handle the national unity issue and best represent the values of Canadians.”

Easier said than done, to be sure, but national unity is not necessarily about centralized programs and interventionist economics. It is more about establishing priorities, articulating values, giving direction and speaking up for the interests of the people of Canada against those who would divide us into a community of communities, ten dukedoms, five regions, and two or more nations.

Ron Graham is an award-winning journalist and the author of The Last Act: Pierre Trudeau, the Gang of Eight, and the Fight for Canada.