Maybe digging into Stephen Marche’s new book, The Next Civil War, while in West Virginia — where Donald J. Trump won nearly 70 percent of the vote more than a year ago — wasn’t wise. Maybe reading Marche’s book in a state where forty-nine of the fifty-five counties were in one of the two highest categories of COVID infection and where the governor, diagnosed a few days later with an inconvenient case of the virus, had lifted the indoor mask mandate six months earlier showed bad judgment on my part. Maybe spending a good deal of the week of the first anniversary of the U.S. Capitol insurrection poring over an argument setting out how the world’s oldest, and arguably once the best, democracy soon will be in tatters distorted my perspective.

But I can say this: Marche’s 250 pages or so constitute a terrifying book, scarier than anything contemplated by Stephen King or Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley or Daphne du Maurier.

Read it and weep. For in these pages is the prospect of additional insurrections like that of January 6, 2021, but likely of another order entirely. There is political and social dysfunction. Marauding militia. Assassinations. State secessions. Maybe the devolution of the United States into four separate countries — likely not, as Shakespeare put it in the opening of perhaps his most accessible tragedy, “alike in dignity.” Read it and weep — that is, if you dare.

You might enter the book thinking of It Can’t Happen Here, perhaps not realizing that the title of Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel is a cynical warning, for “it”— the ascent of a dictator and the destruction of public order — does happen here, and by “here” I mean Lewis’s fictional version of the United States. You might complete Marche’s book thinking that someday the author may sadly say, “I told you so.” And I am not referencing the 1988 Randy Travis song.

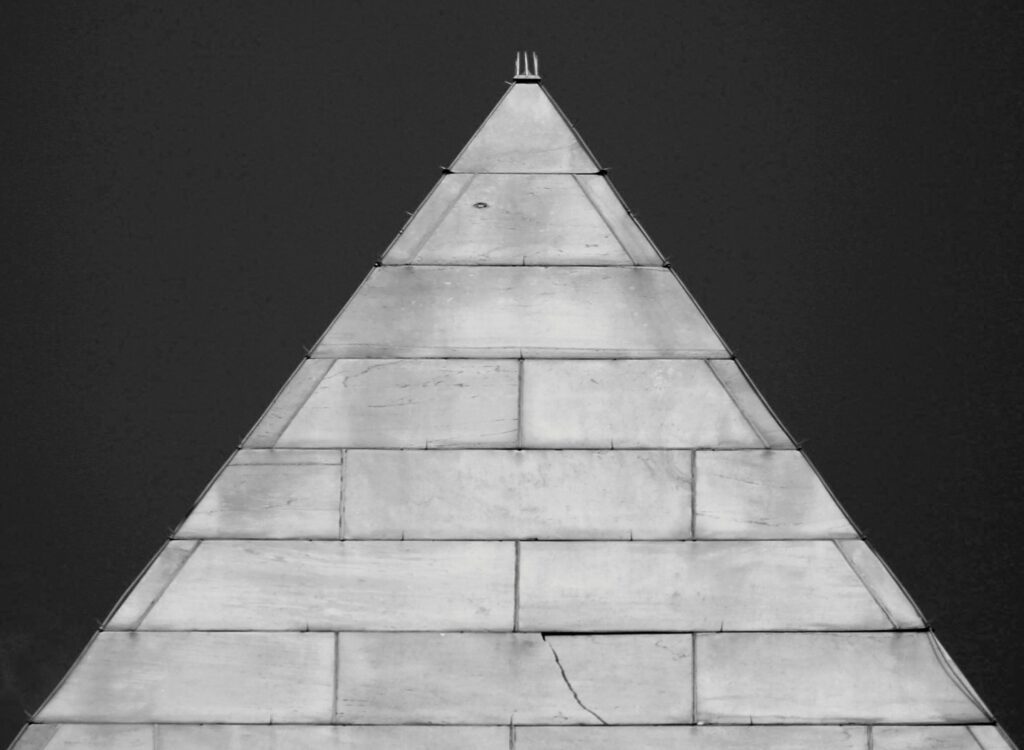

A powerful symbol is cracking.

Reuters; Alamy

Let’s stipulate from the start that the doomsday narrative about twenty-first-century America is told more often and with more feeling in Canada than below the border, though it’s not unknown in the United States. Above the forty-ninth parallel, it’s nothing short of an editorial epidemic. That doesn’t make the narrative less realistic, only less prominent at ground zero. A cursory look at polling data demonstrates that Americans worry, too, about the destiny of their experiment. For example, a CBS News poll released the week of January 6 found that two-thirds of Americans view the 2021 storming of the Capitol as a harbinger of increasing political violence rather than as a one‑off incident. A Quinnipiac poll released a week later showed that a majority believe democracy is in danger in their country.

But no matter your viewpoint, or where you live in North America or beyond, a passage like this one, appearing three-quarters of the way through The Next Civil War, cannot be anything but arresting:

One way or another, the United States is coming to an end. The divisions have become intractable. The political parties are irreconcilable. The capacity for government to make policy is diminishing. The icons of national unity are losing their power to represent.

Let’s examine that argument. There are five sentences to the excerpt. No one who is even barely sentient can plausibly deny the truth of sentences 2, 3, 4, and 5. They are as plain as the evening glow of the Capitol’s dome. The sentence that seems outré is the first one. But if the following four sentences are true, might the first be as well?

And if it is, can a reasonable person argue with the very opening of this book? “The United States is coming to an end,” Marche writes. “The question is how. Every government, every business, every person alive will be affected by the answer.”

Marche’s argument is rooted in the notion that America “is descending into the kind of sectarian conflict usually found in poor countries with histories of violence, not the world’s most enduring democracy and largest economy.” It’s an argument built on yesterday’s newspapers and on websites and cable broadcasts — but also on economic forecasts, algorithms from political scientists, and accounts of the past by scholars of civil wars, not only the one fought by Abraham Lincoln but those across the globe too. One key to understanding all of this rests in another Marche passage:

The Democrats represent a multicultural country grounded in liberal democracy. The Republicans represent a white country grounded in the sanctity of property. America cannot operate as both at once.

Let’s do another deconstruction exercise. No one could plausibly argue with the first sentence: some 36 percent of Joe Biden’s vote in the 2020 election came from people of colour, according to the Pew Research Center. Nor is the second sentence the slightest bit remarkable: 85 percent of Trump’s vote came from white people. What is at issue is the third sentence. Can America operate as both at once?

Of course, a country cannot be multicultural and pretty much all‑white at the same time; that is a logical contradiction. But we cannot know whether it can operate with two parties with such disparate profiles. That is the question of the age.

An essential element of the cultural survival of the United States when it was at the peak of its power, influence, self-confidence, prosperity, and internal peace — from the middle of the twentieth century to almost the end of it — was that the two parties, while holding different visions, were not in an all‑out war. A liberal such as George S. McGovern of South Dakota, the defeated 1972 Democratic presidential nominee, could still work with a conservative like Bob Dole of Kansas, the defeated 1996 Republican presidential nominee, to produce legislation that provided food stamps for the poor. Other examples — the united front of the conservative GOP senator Orrin G. Hatch of Utah and his liberal Democratic colleague Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, on education — abound.

One explanation of why American politics once worked is that the two parties themselves didn’t function in any way recognizable in Canada or Europe. They lacked ideological rigidity, for there were liberal Republicans (mostly in the Northeast and the Northwest) and there were conservative Democrats (mostly in the South, in large measure because of resistance to racial integration but also for historical reasons dating back to the real Civil War). That’s no longer the case. The parties once made no sense, and now they do, which in a way is part of the contemporary tragedy. There was a lot to be said in favour of the illogic of the American party system.

Today, the most conservative Democrat on Capitol Hill is still more liberal than the most liberal Republican. There is no intersection in the vast Venn diagram of American politics nor in the vast landscape of the United States. Just over a year ago, urban areas sided with Biden and rural areas with Trump. The same pattern held four years earlier with Hillary Rodham Clinton and Trump.

But will that split bring on a civil war?

I do take issue with one of the foundational notions of Marche’s thesis, that “being Democrat or Republican is a tribal identification rather than a commitment to particular policies.” I buy the first half, and I have made the “tribalism” argument myself. But I am skeptical of the second half: that there is no commitment to particular policies. For all their stylistic differences, Trump, the GOP Senate leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, and even Mitt Romney of Utah have almost precisely the same views on taxes, abortion, and big government. Likewise, the wing of the Democratic Party that includes Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez shares remarkably consistent views on child care tax credits and taxing the wealthy with the rest of the party’s lawmakers, with the exception of Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin of West Virginia (that state again!). In fact, the day I wrote this review, the Pennsylvania representative Conor Lamb, a devoutly moderate Democrat who is sometimes at odds with the party leadership and who is a candidate for the Senate this year, announced he would support ending the filibuster, putting him in line with much of his party on the principal internal political issue on Capitol Hill.

To put my argument more simply: If you want to battle climate change, you’re a Democrat. If you want to battle Washington spending, you’re a Republican.

At the same time, the fact that there are now ironclad, disciplined commitments to particular policies in the two parties is one of the reasons the country is in this mess. The days when Republican and Democratic lawmakers played pickup basketball in the House gym together, shared tables in the Senate Dining Room to consume the ghastly Senate Bean Soup together, and created mix-and-match legislative coalitions together are long gone.

True, Marche invites us to add in some other incendiary factors, including the wealth gap and the effect of climate change on economic stability. He warns that “every society in human history with levels of inequality like those in the United States today has descended into war, revolution, or plague. No exceptions.” Pour in social media and the braying hyenas of cable news, and you have a recipe for — well, civil war.

Several years ago, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences undertook an eighteen-month project on civil wars, violence, and international responses and found that thirty civil wars were under way in 2018. Many of them, including conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, were (and are) deeply significant and pose substantial threats to global order. But it is not only the view of an American semi-particularist like me to argue that another American civil war would hold even more important, even more unsettling, even more dire consequences.

Stephen Marche, born in Edmonton and a resident of Toronto, makes the case this way:

Even if breaking up is the sensible option, even if it’s better for ordinary Americans, let’s be clear about the stakes here. If the American experiment fails, and it is failing, the world will be poorer, more brutal, lesser. The world needs America. It needs the idea of America, the American faith, even if that idea was only ever a half-truth. The rest of the world needs to imagine a place where you can become yourself, where you can shed your past, where contradictions that lead to genocide elsewhere flourish into prosperity.

And how does it play out? With guns, mostly (the country is awash with them). But also with violently colliding views of who is a “patriot” (the forces of the government who try to assert conventional authority, or the rebels who portray the government as oppressors and occupiers?). One dirty bomb in the Capitol (we who once worked in Washington and worried about dirty bombs thought the main threat was from al Qaeda) would test government’s authority. One presidential assassination (and these are not exactly unknown, having occurred in 1865, 1881, 1901, and 1963) would do the same.

Marche is no fabulist, and he offers some suggestions that have the potential of being solutions. First, acknowledge the problem. (“There is one hope,” he writes, “that must be rejected outright: the hope that everything will work out by itself, that America will bumble along into better times.”) Second, cultivate the “American spirit” and recover its “revolutionary spirit.” Third, junk the electoral system and maybe the Constitution, and convene a second constitutional convention.

The last such convention, conducted in sealed quarters during a particularly beastly Philadelphia summer, ended 235 years ago. The next one, at least, could be held with air conditioning and with fresh breezes — no, with gale-force winds — of urgency. But good luck with finding contemporary versions of James Madison, George Washington, and Benjamin Franklin. It was Franklin, after all, who was reported to have said — the quote may be apocryphal but in modern terms it may be justly apocalyptic — that the 1787 document presented the young United States with “a republic, if you can keep it.”

In truth, the sinews of the United States are weak. The country talks about the rule of law, but it really is governed by a separate, uncodified law of rules. They are little more than assumptions: Losers are supposed to acknowledge the achievement of winners without whining or protests. Changes in power are supposed to be orderly and celebrated. The ladder of social mobility is supposed to be planted on solid ground. Respect for the past is supposed to be universal and often fawning. And the notion about what America is, what it means, and how to salute its greatest ideals and ambitions, and above all the precept that it is “one nation under God”— a phrase once repeated, right hand over heart, by all schoolchildren, but less universally today — are supposed to be part of the nation’s common heritage. And also of its common destiny.

All that is uncertain now. Stephen Marche is right: it could happen here. I do pray that he won’t be able to say “I told you so” any time in the near future. But in the course of this gloomy reading, I was reminded that, as the contemporary argot has it, I am a person of privilege: I have a Canadian passport.

David Marks Shribman teaches in the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He won a Pulitzer Prize for beat reporting in 1995.