For generations, the Civil War narrative about Canada (which was not quite a country at the time) and the United States (which had split into two) remained pretty consistent. It was both simple and satisfying: Canada, bright beacon of freedom for enslaved Black people, had been a welcoming land of refuge, the last stop on the Underground Railroad that carried some 30,000 to safety and emancipation.

Countless children’s books have been written on this theme, with about two dozen currently in print, including The Underground Railroad: Next Stop Toronto!, by Adrienne Shadd, Afua Cooper, and Karolyn Smardz Frost. Museums sprang up about it in, among other places, Emeryville, Ontario; Niagara Falls and Ausable Chasm, New York; Cincinnati, Ohio; even Nebraska City, Nebraska. Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad, an imaginative and impactful novel from 2016, won a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award, on its way to becoming a television miniseries. The United States is planning to substitute on its twenty-dollar note an image of Harriet Tubman (arguably the principal conductor of the Underground Railroad) for the one of Andrew Jackson (formerly celebrated as the rugged personification of American democracy, now derided as a slaveholding genocidal fighter of the Five Civilized Tribes). “Canada was at the top of the Underground Railroad,” Margaret Atwood once said. “If you made it into Canada, you were safe unless someone came and hauled you back.” That all‑aboard! metaphorical train of refugee-passengers operated again during the Vietnam War.

Julian Sher’s The North Star: Canada and the Civil War Plots against Lincoln isn’t so much a work of revisionism as it is a work that shifts the vision. The Underground Railroad’s place in history remains intact: still a great phenomenon, still an emblem of humanitarian activism that is at the heart of modern Canada’s self-image, still a shining star in the safe passage of enslaved people. But that is just part of the story. Sher presents a new take on this land’s role in the War between the States — and beyond. Here be dragons, however: Canadian financiers aided the Confederate States of America. Canadians conspired with the seceded South. Canada was home to sympathizers with the cause of the Stars and Bars. Canadian spies, kidnappers, bank robbers, border raiders, firebombers, and blockade runners played their parts. There were Canadian supporters behind the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the postwar harbouring of Jefferson Davis, the first (and only) president of the Confederacy. Talk about the local angle!

Overall, Sher does not take a cudgel to the common view of the Civil War, which unfolded across five Aprils, as the novelist Irene Hunt phrased it, from 1861 to 1865. In many ways, he offers a conventional account of the conflict, of the abolitionist zealot John Brown, of Lincoln, and of many others who are prominent figures in well-respected and broadly consulted chronicles. His contribution is more inclusion than exclusion: he simply broadens the horizon to acknowledge long-forgotten — more precisely, long-ignored — elements of the period.

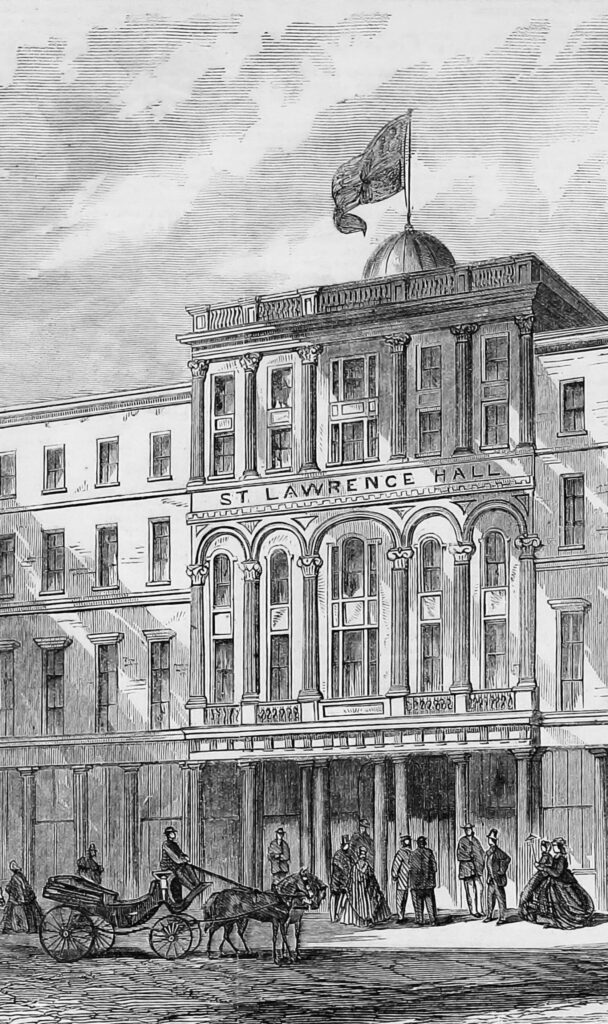

A Confederate hot spot on St. James Street.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1861; Alamy

Much of the story Sher brings to light, it seems likely, will be ignored in the United States, which may be examining the era with fresh eyes but, alas, with eyes that tend not to wander northward (indeed, they tend to glaze over when the word “Canada” is uttered). There the emphasis — and controversy — is now on the roots of slavery itself and the primacy in the country’s history of 1619, the year enslaved Africans first landed on American shores. Canada, as always, is an afterthought — if a thought at all. But at least for Canadians, Sher’s book provides a fuller — and, it must be added, thoroughly captivating — perspective on the Civil War and its aftermath, with Montreal emerging as a comfortable home for Confederate spies, Toronto as a seat of financial conspiracy, and the colonies that would soon form a new nation as a cauldron of conspiracies and filibustering.

Sher reminds us that many Canadians served in Union forces, including 15,000 to 20,000 Canadiens and 2,500 Black men. At least twenty-nine earned the Medal of Honor, the highest military decoration for Americans. Five became generals. An estimated 5,000 to 7,000 died.

The Canadians who sided with the rump of the United States played sometimes significant roles. There was Anderson Abbott, the first Black doctor in Canada. He worked for the Union and later became the medical superintendent of Chicago’s Provident Hospital. There was Alexander Augusta, the highest-ranking Black officer in the Union Army. He became the first Black person to administer an American hospital and the first Black military officer buried at Arlington National Cemetery, across the Potomac River from Washington. There was Edward P. Doherty, who fought at the Battle of Bull Run, about thirty miles southwest of the Capitol’s unfinished dome, in 1861. He later led the effort to hunt down John Wilkes Booth, served alongside Buffalo Bill Cody, and was also buried at Arlington. And there was Emma Edmonds, a prominent field nurse who disguised herself as a man named Franklin Thompson.

At the same time, many of Canada’s elites sided with the Confederacy. Henry Starnes, who both before and after the war won election as mayor of Montreal, was involved in complex money-laundering schemes that assisted the new government in Richmond, Virginia. Addressing the Charlottetown Conference in 1864, John A. Macdonald spoke of “the gallant defence that is being made by the Southern Republic.” The Confederate Secret Service was also active in Canada, led by Jacob Thompson, an outspoken white supremacist, and Clement Clay, whose portrait was on the Confederate one-dollar bill. Four Kentucky teens mustered in Quebec for guerrilla activities that included an attack on St. Albans, Vermont, and a botched effort to burn down New York City. Another Kentuckian, Luke Blackburn, used Canada as a base while planning to weaponize clothes from Bermuda that he believed were contaminated with yellow fever, the vain hope being to mount a biological attack on the Union. (He didn’t know that the scourge was transmitted by mosquitoes, not garments.)

After the outbreak of fighting in April 1861, the Courrier du Canada (which described itself as a “journal des intérêts canadiens”) argued, in language matching that of the Southern intelligentsia, that civil war was the “natural and almost obligatory” outcome when “despotism leads to the abuse of freedom.” Even Great Britain, a base of the slave trade before it became ground zero for emancipation, offered some support for the Confederacy, in large measure because of financial considerations tied to cotton, an essential part of its powerful textile industry.

At the heart of this volume are the Canadians who quietly condoned the Confederate cause, perhaps even the assassination of Lincoln on April 14, 1865. John Wilkes Booth, who killed the sixteenth president in Ford’s Theatre in Washington, visited Canada six months before he pulled the trigger that Good Friday. The trip provided him allies in his endeavour, as well as the escape route that he would take. “Booth could not have carried out the most famous assassination in history when and how he did,” Sher argues, “without the inspiration, tacit support and indirect backing from the highest levels of the Confederacy in Richmond and Canada.”

During his time in Montreal, Booth became a habitué of Dooley’s Bar in the St. Lawrence Hall and boastfully said of Lincoln, “Whether re-elected or not, he would get his goose cooked.” According to Henry Hogan, who owned the hall, “It was recalled by the friends of Booth that just before leaving Montreal he told them that they would hear in a short time of something that would startle the world.” At that same hostelry, a clergyman, reflecting on the death of the president, said, “Lincoln had only gone to hell a little before his time.”

The race to find Booth had a distinctly Canadian flavour, as well. It was Doherty, born in Quebec, who helped track him down and who told the fugitive actor, holed up in a barn, “We want you and we will take you dead or alive.” When he finally came face to face with Booth, Doherty noticed that “his eyes bore that piteous expression characteristic of a hunted deer.” As for the assassin’s accomplice, the American John Surratt, he took refuge, as thousands of the enslaved had done, in rural Quebec, fleeing Montreal in a canoe to Saint-Liboire, fifty miles to the southeast, where he was cosseted by Catholic clergymen. Later he returned to Montreal and made his way to Europe — before being caught in Egypt and brought back to the United States.

Sher’s book is a powerful reminder — one of many in recent years — that just as Canada was not simply a bystander in the Civil War, it was no conscientious objector to slavery.

Although Canada was the desperate destination of many runaways, this country’s record on bondage is not unblemished. A decade after enslaved captives began to arrive further south, Canada saw its first slave sale, when English traders sold a six-year-old boy from Africa to a French clerk. After the Revolutionary War, advertisements for enslaved workers appeared in newspapers such as the Montreal Gazette. It is true that by 1833 — three decades before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, itself a symbolic but halfway measure meant to free “all persons held as slaves” in territory the Union did not control — the British Imperial Act banned slavery. It also is true that there remained manifold examples of the enslavement, in the practical sense if not authorized by law, of Indigenous people here and throughout the empire long thereafter.

Much of this was not exactly unknown, then as now. “The assassination plot was formed in Canada, as some of the vilest miscreants of the Secession side have been allowed to live [there],” The Atlantic Monthly wrote shortly after Lincoln’s death. “The Canadian error was in allowing the scum of Secession to abuse the ‘right of hospitality.’ ” But Sher, acting like a magnet that sweeps to its poles all the shavings of Canadian involvement in the conflict, has assembled a remarkable assortment of surprising connections.

His book takes its title from Martin Luther King Jr., who said in his 1967 Massey Lectures that “deep in our history of struggle for freedom, Canada was the North Star.” The civil rights leader added, “So standing today in Canada I am linked with the history of my people and its unity with your past.” It is worth noting that King borrowed the North Star image — itself ripe with metaphors of a celestial object that provides light and direction — from the North Star newspaper founded in 1847 by the abolitionist Frederick Douglass and dedicated to assailing the “ramparts of Slavery and Prejudice.” The creators of the paper, Douglass declared in his first editorial, had “writhed beneath the bloody lash” and are “one with you.”

As the defeated president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis had much the same impulse as the Black people he reviled: after the war, he shipped three members of his family to Montreal, where they eventually lived at the corner of Ste‑Catherine and Union. “We could not but sympathize with the Southerners,” said Sarah Lovell, the wife of a prominent publisher, “in the loss of their luxurious homes and of the many near and dear to them.” Davis, in a sort of exile, nonetheless travelled easily throughout southern Ontario and, with his family, found welcome in Quebec. As Sher observes, “It says a lot about Canada’s role in the Civil War that, for comfort and protection, the first place the former president of the Confederacy headed was not south to Memphis, Montgomery or Mississippi, but north to Montreal.”

Much of Niagara — the town we now know as Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario — became a kind of asylum for Confederate States of America exiles. John C. Breckinridge — who served as James Buchanan’s vice-president, ran an unsuccessful presidential campaign of his own in 1860, and fought as a Confederate general — established a home there. So too did Jubal Early, a veteran of the Indian Wars and the Mexican War who served as a Confederate general in several storied battles, including Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. James Mason, a former member of the House of Representatives and the Senate who became the Confederacy’s envoy to London, lived there as well.

Decades later, in 1957, the United Daughters of the Confederacy sponsored a bronze plaque that was attached to the west wall of the Hudson’s Bay department store in Montreal, commemorating the Davis family’s residence and refuge in the city. In French, it read, “To the memory of Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States, who lived in 1867 in the home of John Lovell, which was once here.” Sixty years later, following a rally of white nationalists in Charlottesville, Virginia, two workers, with a screwdriver and a hammer, removed it. The plaque is gone. The shame remains.

David Marks Shribman teaches in the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He won a Pulitzer Prize for beat reporting in 1995.

Related Letters and Responses

James Brierley Westmount, Quebec

Patrice Dutil Toronto