With apologies to Steven Pinker, who (correctly) keeps telling us that this is the best time to be alive: it sure doesn’t seem like it sometimes, at least not when we scan the bleak social and political landscape of the past year. But hope we must. In that spirit, the recent mid-term elections in the United States may be a source of some optimism for the future. On November 8, 2022, the voters of the world’s most important liberal democracy took a good look at the pack of populists hand-picked by the former president Donald Trump — the election deniers, the moralists, the hate-mongers — and, for the most part, said, “No, thanks.” So has the recent wave of far-right populism crested?

Populism — an anti-establishment political stance that positions the assumed will of “the people” against the supposed interests of “the elite”— is not the exclusive domain of the right. Think of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela or the Syriza Party in Greece, both on the left. However, it is the populism of the far right that today feels the wind in its sails. Last year alone, Italy elected a prime minister from a party with a fascist past; a Swedish party with neo-Nazi roots won the second-most seats in the country’s parliament; Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (“Offenders from France, in prison; foreigners, on planes!”) secured more than 40 percent of the vote in the French presidential election; and Israelis learned they will be governed by a coalition that includes ultranationalists and Jewish supremacists. These wins come on the heels of a strong electoral showing for the far right in Germany in 2021 and follow years of nationalist, xenophobic leadership in Poland and Hungary.

While the latter two countries have relatively shallow liberal roots, the same cannot be said for Canada, where 2022 saw several populist politicians do quite well. Danielle Smith, with degrees in English and economics and a career in journalism, became leader of her party — and thus premier of Alberta — by picking fights with “the elite” in Ottawa and in her province. “The choice is clear,” she posted on Facebook last September: “more woke establishment control or strong leadership that puts Albertans and our freedoms first!”

During Quebec’s forty-third general election campaign, François Legault linked immigration with extremism and violence (the premier later apologized), while Jean Boulet, the immigration and labour minister, asserted on Radio-Canada that “80 percent of immigrants go to Montreal, don’t work, don’t speak French, and don’t adhere to the values of Quebec.” (The MNA for Trois-Rivières later said he had chosen his words poorly.) Despite these ugly and inaccurate claims, Boulet waltzed to re-election, and Legault’s Coalition Avenir Québec won the largest majority the province has seen in decades.

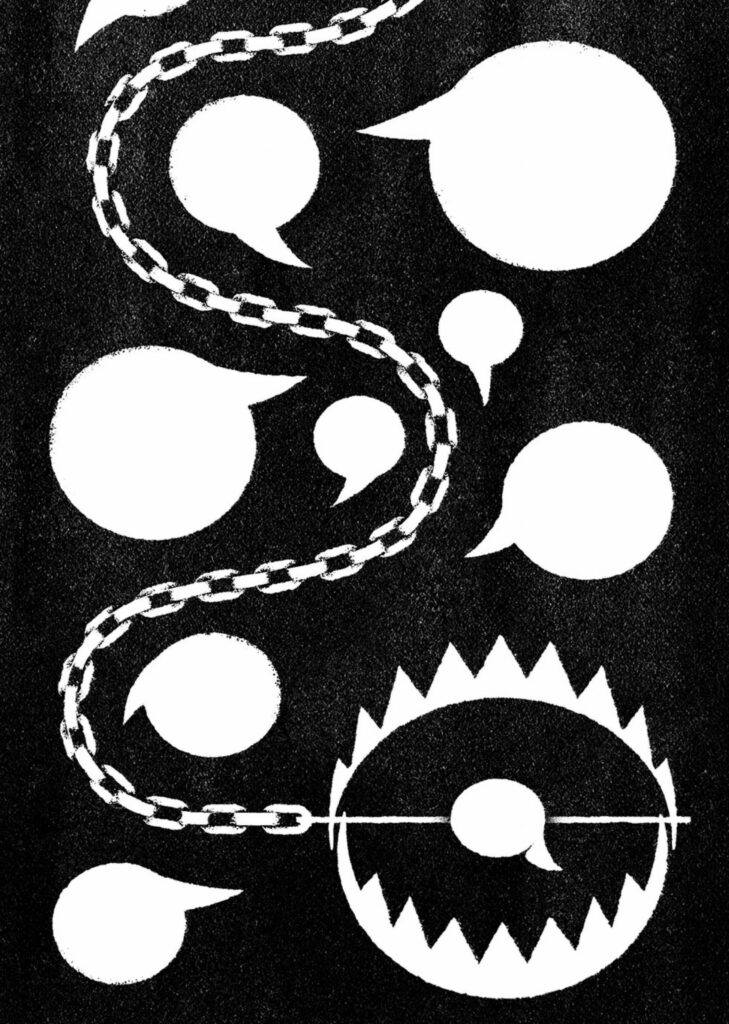

Beware the fake charms of strongmen.

Karsten Petrat

Then there’s Pierre Poilievre, who became the leader of the Conservative Party by, at various times, promising to fire the conventionally independent governor of the Bank of Canada for not acting in accordance with his own, somewhat idiosyncratic views on monetary policy; actively promoting the conspiracy that shadowy global oligarchs at the World Economic Forum (a favourite target of populists) are planning to impose authoritarian global government to remake all societies; and courting far-right extremists, including one who has been deemed a national security threat by federal authorities.

Why have liberal societies like ours — ostensibly tolerant and pluralistic — fallen under the sway of conspiracy-minded demagogues, nationalists, and xenophobes? Is this just a passing phenomenon, as the recent U.S. mid-terms might suggest, or will it become even stronger and uglier? These are some of the questions asked in two books: Has Populism Won?, by the political scientists Daniel Drache and Marc D. Froese, and The Age of the Strongman, by the veteran Financial Times columnist Gideon Rachman.

Both books are accessible surveys that speed along without skimping on weighty issues, though readers might benefit from at least a passing acquaintance with political theory, history, and international affairs. Has Populism Won? dives into the architecture of contemporary populist movements, while The Age of the Strongman traces the rise of contemporary autocrats in non-democratic states and shows how aspiring Western authoritarians try to play tough, just like their illiberal counterparts. Above all, these books alert us to the very real dangers that contemporary populists pose to liberal societies.

“Populism,” write Drache and Froese, “is a way of speaking about politics that sets up a moral dichotomy and creates conflict between the ‘true people,’ who are honest and good, and the ‘elite,’ who are evil and corrupt. The populist leader is an authoritarian who believes that centralizing his own power requires undermining democracy.” Rachman uses similar language in tracing the global surge of authoritarians over the last two decades. “Typically,” he writes, “these leaders are nationalists and cultural conservatives, with little tolerance for minorities, dissent or the interests of foreigners. At home, they claim to be standing up for the common man against the ‘globalist’ elites. Overseas, they posture as the embodiment of their nations. And, everywhere they go, they encourage a cult of personality.” We’d be wrong, though, to assume this last part happens only in countries like China, Russia, or Turkey. As Rachman notes, the current version of the Grand Old Party eschewed a platform in the 2020 U.S. election in favour of a one-line declaration: “The Republican Party has and will continue to enthusiastically support the President’s America-first agenda.”

Drache and Froese discern a populist ecosystem made up of angry voters, celebrity-seeking activists who cynically stoke that anger, and opportunists who leverage discontent for power. Rachman adds that authoritarian leaders show contempt for the rule of law and base their politics on fears held by the majority. Importantly, the authors do not minimize the anger and fear that many Western citizens feel and that are at the root of populist politics. “Populists represent an antidemocratic solution to the problems facing liberal democracy, of rising inequality, decaying institutions, and political cultures that emerged in the twentieth century and no longer capture the many pressing concerns of twenty-first-century citizens,” note Drache and Froese. In this vein, Has Populism Won? looks at the Great Recession of 2008 (and its aftermath), the eurozone crisis, and the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It also devotes ample attention to the larger macro-dislocations of the past several decades. Similarly, in The Age of the Strongman, Rachman describes the ascent of autocratic figures who were “in revolt against the liberal consensus that reigned supreme after 1989.”

These writers accurately report how Western voters who are most attracted to nationalist parties and populist leaders are those who have borne the brunt of the uneven economic effects of globalization. This pain has been further, and intensely, exacerbated by a profound sense of cultural upheaval — what the British sociologist Anthony Giddens once called “the intensification of worldwide social relations,” itself a result of globalization, as well as the migration and refugee crises of the past decade. As the American scholar Colin Dueck has written, “The very same rise of post-materialist cosmopolitan, multicultural issues and values that inspire liberals has also triggered a culturally conservative reaction from those segments of the public unpersuaded by the benefit of such changes.”

Donald Trump’s appeal in 2016 was largely based on demographic trends in the U.S., where whites are projected to make up less than 50 percent of the population in the next twenty years. “Trump became the champion of white voters who felt economically or socially insecure and who, crucially, blamed their situation on ethnic minorities,” Rachman explains. He was hailed as “the only candidate willing to stop immigration,” a perception that helped him win ”almost 80 percent of the votes of non-college-educated white men.” (During the campaign, the future president declared, “I love the poorly educated!”)

If populist leaders have identified legitimate grievances, what have they done about them? Not much. Rather, the authors of these two books contend, populists cynically use those fears and that anger to gain, hold, and expand their own power. “The populists judge that a narrative in which the true people are beset on all sides by the tyranny of evil foreigners is the best way to maintain their grip on their base,” write Drache and Froese. They often do this with the help of useful media activists and political ideologues, who, Rachman argues, “have helped to create the intellectual backdrop against which the strongmen operate, providing some of the key ideas, arguments and slogans that underpin populist nationalism.” (His book helpfully traces the worldwide connections among some of them.)

Essential to this narrative are the lies, conspiracies, and hot-button issues that are fed as perpetual Pavlovian treats to hungry and primed audiences — a “firehose of falsehoods,” to use a phrase Rachman borrows from the RAND Corporation, or “dark narratives,” as Drache and Froese put it. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic has been effectively used by populists to gain a hold on power (Smith in Alberta, for example) or cement it (Xi in China). Fellow-travellers have exploited it online and in the mainstream media, as when Fox News hosts routinely disparage vaccines, despite being vaccinated themselves as a term of their continued employment.

Consider also the great replacement theory, which has become state ideology in Viktor Orban’s Hungary and clickbait in the swamps of far-right social media influencers, including among American Republicans. “Joe Biden’s five million illegal aliens are on the verge of replacing you, replacing your jobs, and replacing your kids in school,” the Georgia congressional representative Marjorie Taylor Greene said in a recent speech. “And coming from all over the world, they’re also replacing your culture.”

Another theme is the exploitation of gender politics, as seen with Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law, championed by the governor and potential Republican candidate for president Ron DeSantis, which bans the teaching of sexual orientation to young children; with the Polish president Andrzej Duda, who maintains that LGBTQ rights are “worse than Communism”; and with an influential Vladimir Putin ideologue, quoted by Rachman, who sums up liberalism as “no borders between countries and no distinction between men and women.”

Polarized electorates and disaggregated (or state-controlled) media make it relatively easy for populists to whip up negative emotions and ride them to power. “Populist leaders like to portray themselves on the global stage as ‘system smashers,’ ” write Drache and Froese. It is far harder to find just and effective solutions to the complex problems facing contemporary societies: that is, to lead.

Both of these books make it clear that, in practice, today’s far-right populism is a metastasizing politics of extreme grievance and little else. In the memorable words of David Frum, following his debate with the Trump Svengali Steve Bannon, populists don’t deliver because they “have no plans and no plans to make plans.” Today’s Western wannabe mini-despots believe that all problems — no matter how complex — have simple solutions and that nuance is a four-letter word. This is politics where a double-middle-finger salute masquerades as policy, dark emotions are celebrated over reason, and childish minds derive more pleasure from upsetting the status quo than satisfaction from getting things done.

The Age of the Strongman and Has Populism Won? both address the threat of nationalist populism to the liberal international order, which is already creaking from its inability to accommodate the return of China as a great power. They illustrate very well how powerful illiberal states practise the politics of resentment on a global scale and manipulate angst to help speed along the destruction of liberalism from within. “For right-wing and nationalist politicians spanning the spectrum from cultural conservatives to outspoken racists, Putin has become something of an icon,” Rachman offers as an example. “He is a symbol of defiance of the Western liberal establishment, epitomized by figures such as Hillary Clinton and Angela Merkel, with their encouragement of immigration, gay rights, feminism and multiculturalism.”

This homegrown hostility to pluralism is alarming. Too many people in liberal democratic countries are falling for the fake charms of strongmen and their useful idiots in the West. As Drache and Froese point out, these are self-inflicted wounds: “We listen to the lies; we are seduced by conspiracy theories. We don’t want to do the heavy lifting required of an informed public.” Yes, when Western progressives demand an immediate utopia, friction results, especially among those whose lives have undergone severe dislocations in the past two or three decades. But the answer to such demands must not be the return to some fairy-tale Arcadia that cruelly imposes so-called traditional values and hierarchies. Liberalism cannot survive without accepting that different groups of people have different interests and value different things, all of which are legitimate. Liberalism doesn’t work if we don’t accept the inherent worth of all individuals, no matter who they are or where they’re from. If we won’t defend those principles, what’s the point in standing up to autocrats overseas? Those who ignore this fundamental truth — or, worse, play to rhetoric that denies it — will lead us straight into a dead end.

As for populism in Canada, the world won’t turn on what happens in this country — though it’s certainly not helpful when even medium-sized liberal states become less so. But the populism we’re seeing here is certainly bad for Canadians, all of whom have unquestionably benefited from our liberal traditions.

Have the populists won? None of these authors have a crystal ball, but they don’t see this movement disappearing quietly. It’s past time, then, for us to remember that, of all political beliefs, only liberalism is based on respect for the dignity of each person. If you want to be angry about something, be angry that today’s populists want to take that away. And take heart whenever you see a sign they aren’t succeeding.

Dan Dunsky was executive producer of The Agenda with Steve Paikin, from 2006 to 2015, and is the founder of Dunsky Insight.