When it comes to wines, there are almost endless varieties. The same can be said of politicians. A few become prime ministers, while others end up as one-term members of Parliament. Several are elected as party leaders, while many more sit as backbenchers. Some of them become respected federal cabinet ministers, while others relish their work at the provincial level.

Bob Williams and Michael Wilson were both successful politicians, but their vintages were markedly different. Williams was born into a working-class family in East Vancouver and would serve as a straight-shooting NDP cabinet minister under Dave Barrett, the premier of British Columbia. Wilson was born into a self-described “privileged” background in Hamilton, Ontario, and would serve as a straitlaced federal finance minister in Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government.

Yet the two men’s recent autobiographies reveal some similar notes and characteristics. Using Power Well: Bob Williams and the Making of British Columbia looks at one man’s “atypical life story” and colourful career in Lotusland, whereas Something within Me: A Personal and Political Memoir, completed after Wilson passed away from cancer in 2019, offers a more conventional tale of a life in politics. Both books are fascinating, illuminating reads. They also show how a position on the political spectrum doesn’t necessarily define a public figure.

Bob Williams’s honest, forthright, and matter-of-fact approach is visible on every page of Using Power Well. He sees himself as part of a larger community, and he wants to consume every morsel that’s been served to him on life’s plate. A gregarious personality shines through in the book, as does a no-nonsense attitude to life and politics.

“We were poor, and even as kids we knew it,” Williams writes, “but it didn’t matter very much.” He grew up near a city dump in Still Creek and sorted garbage with his Ukrainian neighbours to earn a few pennies. With his nana, he enjoyed visiting Crabtown, along the North Burnaby shore, which contained little shacks with names like Dew Drop Inn and the Last Resort. He remembers those who lived in the shacks, in particular a Scandinavian shipbuilder: “Oscar was only one of the many who would generally be seen as down and out, but for me they were fascinating characters who had created a wonderful life for themselves.”

For Williams, East Vancouver was and remains a “rich mix of childhood friends, class consciousness, sense of place, ethnicities, local organizations, tolerance, brotherhood, camaraderie — all these things. It is home and everything that entails. It’s also a village, with the many generations and associations that a village remembers.” After attending Britannia Secondary School, he went to the University of British Columbia across town. Following graduation, he spent a year with Burnaby’s planning department, before enrolling in the new master’s program at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He worked as a consultant, became a draftsman, and learned about the “pieces of the civic infrastructure” (Vancouver’s sewer system was particularly “intriguing”). He also got a job with the “paramilitary agency” that was the BC Forest Service. “I thought forestry might be a good field to pursue because of my attraction to wilderness, but later thought better of it.” Williams picked up numerous skills along the way that he would soon put to good political use.

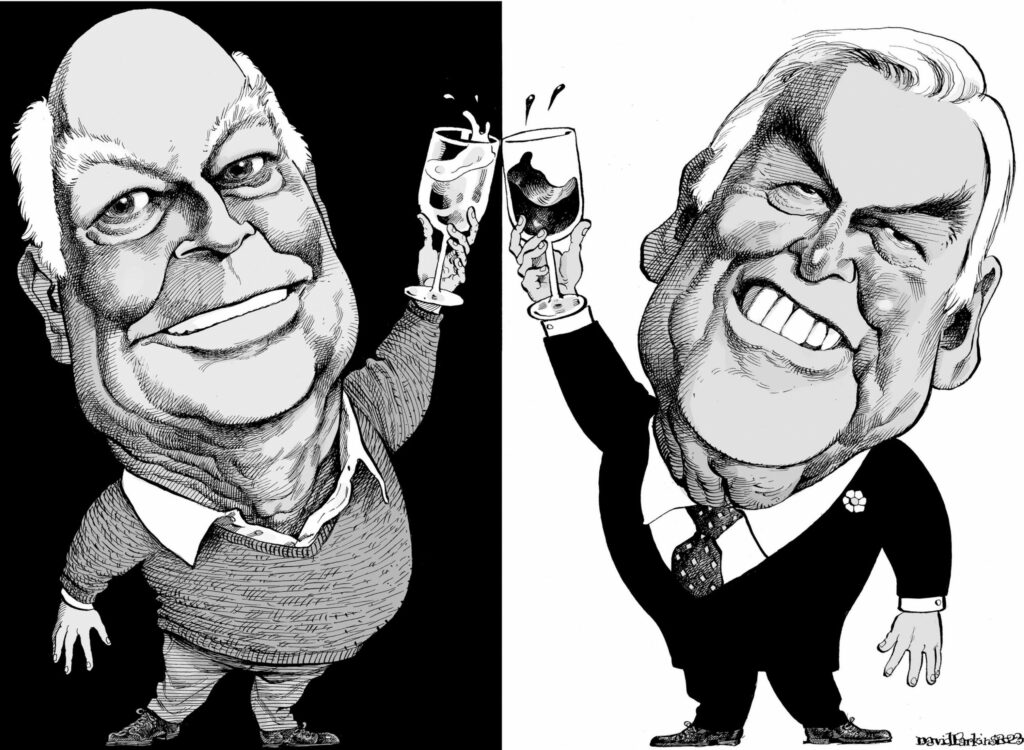

From left to right with the NDP’s Bob Williams and the Tories’ Michael Wilson.

David Parkins

Politically, Williams was firmly on the left. He describes a “Follow John” Diefenbaker rally in 1957, after which he told a friend, a “staunch” Red Tory, that he thought the federal Progressive Conservative leader was a “demagogue.” (Dief was also a Red Tory.) His friend encouraged Williams to join his party of choice, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation: “Her own views were not a consideration.” Some sixty years later, the party’s name continues to resonate with Williams. “I find it overflows with meaning,” he writes. “Co-operation was important back then, just as I believe it needs to be today.”

The political acorn didn’t fall too far from the family tree. Williams’s paternal grandfather, Bill Pritchard, was an early member of the province’s trade union movement. He was also the BC Federation of Labour representative during the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike and briefly became a “fugitive from the law” after it was broken up. Pritchard was arrested and refused to have a lawyer represent him at trial. Instead, he gave an impassioned speech that was published in 1920 as a book, W. A. Pritchard’s Address to the Jury, which Williams describes as “a history of the evolution and the building of modern freedoms for working men and women in the British Commonwealth” and “a standard text for the self-taught citizens of the labour movement.” Pritchard was released from jail to thunderous applause. He became reeve of Burnaby, joined the CCF, and, after a falling-out with its members, switched to the short-lived Social Constructive Party. Following the death of his daughter by suicide in the 1930s, Pritchard moved to Los Angeles for the rest of his life.

Williams was “a little shy” and “still learning” the ins and outs of politics after he joined the CCF. Nevertheless, he immediately began to climb the ladder of success. He became friendly with local activists like Edna Nicols and Harry Whelan, as well as bigwigs like Grace MacInnis, the daughter of the party founder, J. S. Woodsworth. Williams’s first motion —”supporting the idea of municipal industrial estates”— passed comfortably. It was, however, initially opposed by Harold Thayer, the provincial secretary, who didn’t want the party to introduce too many “leftist ideas,” of all things, and who was concerned that “people would think we wanted to own their very toothbrush.” Williams ran for Vancouver city hall in 1964 and won the last council seat when the local Communists, a sizable voting faction, split their vote between him and Harry Rankin, a lawyer who would eventually serve on city council for decades.

In 1966, Williams was nominated as a candidate for Vancouver East, representing the CCF’s successor, the New Democratic Party. He won the seat handily with the other NDP MLA, Alex Macdonald (the province’s ridings were multi-member electoral districts until 1991), and began a lengthy career of public service.

Williams spent his first few years in Victoria on the opposition benches, during the Social Credit premier W. A. C. Bennett’s twenty-year tenure. He didn’t care for the ideology and leadership style of the “old man” and didn’t like the fact that he would turn his back to opposition MLAs when they spoke. Williams now understands that Bennett was “busy lecturing and providing sage political advice to his cabinet and the occasional supplicant from the back bench” when he turned around. Williams also admits that, on certain points, like the importance of Vancouver versus small towns, there was maybe “more to his argument than I’d given him credit for.”

When Dave Barrett and the NDP defeated the Socreds in 1972, Williams was appointed as the minister of lands, forests and water resources.* It was a role he requested and an opportunity to make a difference. “The truth of the matter was we didn’t have a lot of depth in the civil service when we became government,” he acknowledges. “Many people who started out as mail clerks in a ministry became deputy ministers by the end of their careers. Initially I shook my head over the inadequacy of the public service. It was not long, however, before I realized what an advantage it was.” Williams found this time in government exciting, believing “we were going to do what the party and our friends and people in our history wanted.” When Barrett asked his cabinet, “Are we here for a good time or a long time?” they unanimously favoured the former.

As part of the Environment and Land Use Committee, Williams “was basically running five or six ministries. And a lot of the ministers wanted me to run their ministries for them!” Some of his responsibilities included reviews of the Kootenay Canal project and the Pearse Report (from the Royal Commission on Forest Resources), establishment of the Columbia Basin Trust, and creation of the Agricultural Land Reserve, which was “unequalled” in North America. He drafted legislation to create “the Resort Municipality of Whistler,” which remains an important and profitable tourist location, and he helped double the acreage of provincial parks. He was also involved in acquiring and refurbishing an old steamship, the Princess Marguerite, for ferry service between Victoria and Seattle. “It was a wonderful, fun project,” he recalls.

Throughout it all, Williams learned some new things about himself: “With my socialist roots, I didn’t realize I had entrepreneurial instincts until we were in government.” He enjoyed this sense of discovery. After ten years, Williams left politics for the first time, when he resigned his seat in 1976 so that Barrett could return to the legislature after the NDP’s defeat the previous year. Out of office, he decided to “use my entrepreneurial skills learned while acquiring forest companies” to benefit both his family and his community. He started some new businesses and purchased others, including the Barnet Motor Inn in Port Moody and the Railway Club in downtown Vancouver, which featured live entertainment by the likes of k. d. lang. The socialist had transformed into a capitalist of sorts.

There is something of a plot twist in Using Power Well. Williams writes surprisingly little about his private life and makes just a few light references to his marriage to a party activist, Lea Forsyth, at the age of thirty-seven, as well as to a brief dalliance with an unnamed married female secretary. Yet the eighty-nine-year-old acknowledges for the first time publicly that he’s gay — and that it’s the reason he ultimately left politics for good in 1991.

Williams took his old Vancouver East seat again in a by-election in 1984. One day, after being re-elected in 1986, he went to get a coffee “at the old CNIB kiosk just outside the east entrance of the legislature.” Behind him stood a Socred appointee, who asked a question with a “double meaning.” Williams responded, “Okay.” As he walked away, the same man asked him the same question again — and laughed. “It was then I recognized the key code word,” he writes. “In effect, he was saying, ‘I know you’re gay.’. . . I knew they knew I had a gay side, and did not know how they might use it against me. But I’d seen what happened to others. I concluded that I should resign before the next election, and I did.”

Despite how his public career ended, Williams looks back fondly: “I learned over time that the job of the good politician was to use power well. . . . I enlisted the professionals who were best in their fields — economists, planners, lawyers, social workers, consultants — always wanting to know the norms to try to work within them, even on radical projects, but always informed by a sense of history, roots and the public interest.”

Compared with Bob Williams, the late Michael Wilson was a far less bombastic and charismatic individual, and his memoir, Something within Me, is crafted in a more measured way. Nonetheless, it offers plenty of intriguing stories about people, places, policies, and, of course, politics, as well as deeply personal insights.

Born in November 1937, Wilson grew up in comfortable surroundings in Hamilton and later attended Upper Canada College in Toronto. His parents had a “long and happy marriage” and passed on their values to him and his siblings, “not by decreeing what we should or shouldn’t do with our lives, but by celebrating the joy and satisfaction those values provided them.” His father, Harry, had a profound influence on his growth and development, including his belief that intelligence and knowledge are important tools but that you also need to “understand people” to properly succeed. “Among all the skills I acquired and honed through life,” Wilson writes, “the ability to understand and appreciate the concerns of those around me was at least as important as reading a balance sheet and measuring investment risk.”

With his “flair for mathematics,” Wilson studied commerce and finance at the University of Toronto, though his father’s career at National Trust also informed his decision. He struggled at first, living the life of a “quintessential college frat boy” and underachieving in the classroom. Thanks to a couple of fourth-year fraternity brothers, who warned him to either “buckle down” or risk the possibility of failing, he got through his first year with improved grades and an improved attitude. After graduation, he worked in Toronto for Harris & Partners and in London, England, at the prominent merchant banks Baring Brothers and Morgan Grenfell.

Not long after Wilson decided to join the Department of Finance in Ottawa, instead of doing graduate work at Harvard University, he was introduced to a nurse, Margie Smellie, at a Toronto dinner party hosted by a mutual friend. Smellie had met someone with Wilson’s name before and had little interest in being set up. “I know Michael Wilson,” she told the friend, “and I don’t care if I ever see him again!” But she eventually agreed to meet. “Knowing that Michael Wilson Two was (I assumed) quite different from Michael Wilson One,” he recalls, “she agreed to see me again.” They married in 1964 and would have three children.

Wilson had “deeply Conservative” roots, but the person who truly “planted the seeds” for a political career was his godmother, Vera, a “staunch Republican from Minneapolis” and admirer of Dwight D. Eisenhower. She visited in 1952, and though he was still a teenager, his conversations with her “brought politics alive to me.” Within ten years, he was canvassing for the federal Progressive Conservatives.

A friendship with the future federal Liberal cabinet minister Donald Macdonald, with whom he worked in the Finance Department, also contributed to Wilson’s “political bug.” While neither man changed the other’s ideological viewpoint, Wilson took away “an awareness of the contrast between life in business and life in politics.” The goal in business “was to work within the milieu of public policy to attain financial success,” whereas the goal in politics was “to shape and manipulate that milieu for the wider good.” For him, “the distinction between the two was dramatic.” (The friendship remained strong for years, and a “political bond” arose from Macdonald’s support in the 1980s for a free trade agreement with the United States.)

Wilson held the Ontario riding of Etobicoke Centre from 1979 to 1988, through four elections. He ran in the PC leadership race in 1983, but he dropped out after the first ballot and encouraged his supporters to side with Brian Mulroney. Although he had served as a minister of state for international trade in Joe Clark’s short-lived minority government — and originally supported Clark’s candidacy — he told his fellow Conservatives, “I owed my support to the party, not to any individual.” He believed Mulroney “was best equipped to lead the party to victory” and had the “bearing, presence, and political know-how, plus more strength in Quebec than anyone else on the ballot.”

Wilson recounts an anecdote of Mulroney and his wife, Mila, watching “in dismay” as he and a fellow candidate, Peter Pocklington, mistakenly walked past the aisle from their box to what appeared to be John Crosbie’s. The Mulroneys were “recalling the 1976 convention when delegates had rejected Mulroney as an outsider and unqualified to lead the party.” Wilson realized the mistake, “grabbed Peter’s arm and pulled him back to the aisle leading to the Mulroneys, who were naturally ecstatic to see us approaching them.” The Ghost of Political Conventions Past had been narrowly avoided.

Mulroney won the 1984 federal election and appointed Wilson as finance minister. Their friendship and working relationship grew stronger with each passing year. Something within Me examines this remarkable seven-year period of Wilson’s career, along with his tenure as minister of international trade, from 1991 to 1993. Wilson dined with Ronald and Nancy Reagan as well as the royal family and represented Canada on a visit to the Baltic states. He met with the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, and the first Russian president, Boris Yeltsin; helped negotiate the 1988 free trade agreement between Canada and the United States; and introduced the vilified goods and services tax in his 1989 budget.

Wilson’s involvement with many of these issues is well known. Some of his stories and observations about them are less so. For example, he once teased John Bosley for not offering him some chocolate when the House Speaker let him stay at his Centre Block apartment after presenting a budget. So Bosley asked a page to deliver an envelope containing two Crispy Crunch bars to Wilson, who mouthed “Thank you” in response. The next day, the Toronto Sun reported he had said “F*** you!” During talks in Washington, the U.S. Treasury secretary Don Regan assured an assistant that Wilson was a “friend of ours.” Regan shut the door, smiled, and said, “Don’t be offended. He hadn’t realized you’re part of the new government in Canada. If your predecessor had been here, he wouldn’t have talked about things so openly.” Because Regan’s guy (Ronald Reagan) liked Wilson’s guy (Brian Mulroney), things were different. “I can trust you and you can trust me. We can have an easy conversation about anything you want to talk about.”

With respect to the GST, Wilson recalls, he understood the “emotional reaction to the idea of a government finding new ways to stick its hands in the pockets and purses of Canadians.” Nevertheless, he rejects calling the sales tax “regressive,” because such a label “ignores the fact that such a broadly based tax makes it easier to declare and identify exemptions that reflect the ability to pay it.” He also pushes back against the concern it would be “visible.” He explains that this “visible sales tax, adjusted to be as fair as possible, would replace a hidden sales tax”— the old manufacturers’ sales tax, which had been around since 1926 —“that had been patently unfair for decades.”

The eventual success of the free trade negotiations with the U.S. was a point of pride for Wilson, but the entire project nearly unravelled on October 3, 1987, when Washington wouldn’t budge on Ottawa’s condition to include an independent dispute settlement mechanism. It has been mentioned in various sources, including Mulroney’s memoirs, that the tide turned when the prime minister told the U.S. treasury secretary, Jim Baker, that he would call Reagan at Camp David and ask, “Ron, how come the Americans can do a nuclear arms limitation deal with your worst enemy, the Soviet Union, but you are unable to agree on a free trade deal with your best friend, Canada?” Wilson reveals that he personally asked Baker to set up that important call. Would it be possible? “No, it’s not,” the treasury secretary said, smiling. “The President is watching a movie. It’s best not to disturb him.” Wilson wondered which movie could be so “enthralling” that they couldn’t inform the president “of the collapse of an international agreement he had been shepherding for some time.” (He doesn’t say, but it would have been appropriate if it had been Reagan’s favourite Western, High Noon.)

Wilson left politics before the 1993 federal election. He worked on Bay Street and served as chancellor of Trinity College and, later, the University of Toronto. As prime minister, Stephen Harper asked him to serve as Canadian ambassador to Washington, from 2006 to 2009. It was the “only public appointment I could imagine accepting,” Wilson explains. The two men got along well. As Wilson wryly jokes, “Harper revealed that everything he knew about charisma he had absorbed from me.”

Throughout his impressive career, Wilson was active with such organizations as the Canadian Cancer Society and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. He lost his father to cancer and, tragically, his beloved son Cameron to suicide. Wilson became a powerful advocate for the rest of his life, raising awareness of mental health, speaking about his son, raising large amounts of money, and being elected board chair of the Mental Health Commission of Canada in 2015.

“We don’t need warriors on either side defending their perceived turf,” Wilson writes near the end of his book. “We need capable and dedicated people on both sides who acknowledge the overlap”— between the private and public sectors —“and set out to bridge the gap between them.” This was his prime goal in life and politics, and he set out to accomplish it as best he could. His success in finding common ground with both allies and critics in many circles is part of his enduring legacy.

Drawing a straight line from Bob Williams’s life and career to Michael Wilson’s would be a fruitless endeavour. But despite the differing ideologies, economic visions, and personalities, their memoirs speak to a shared love of politics, dedication to public service, and commitment to Canada. We might think of these books, then, as vintage wines made from very different grapes, from very different regions. Nonetheless, they go surprisingly well together.

* The print version of this review incorrectly dated the provincial election to 1971. The magazine regrets the error.

Michael Taube is a columnist for the National Post, Loonie Politics, and Troy Media. Previously, he was a speech writer for Prime Minister Stephen Harper.