The Victorian writer Thomas Carlyle once declared, “No great man lives in vain. The history of the world is but the biography of great men.” Oscar Wilde, on the other hand, believed that biography — having one’s peccadilloes and failings encased in amber —“lends to death a new terror.” More recently, the American novelist Thomas McGuane suggested that any future chronicler of his life ignore him altogether and concentrate on his dogs.

But for readers, it’s not hard to understand the continued appeal of the genre, which offers an insider’s view of the lives — private as much as public — of great men and women. (The latter were excluded by Carlyle, though a tradition of female biography is, of course, many centuries old.)

A human life is as natural an organizing principle for putting major events into context as any, and it has the advantage of pretty firm boundaries, unlike “the Middle Ages” or “the long eighteenth century.” Several years ago, I encountered the epitome of a sharp cut-off point in a biography of Robespierre that ends abruptly at the moment the deposed revolutionary leader’s neck met the guillotine’s blade.

The life writing craft is an ancient one, nearly as old as the writing of history, its close relation. Its variants include autobiography, informal genres such as diaries and letters, and such specialized forms as hagiography and martyrology. Straightforward biography remains enormously popular, judging by booksellers’ shelves, though the past century has seen its lustre fade within academic circles, along with that of political history, which also focuses on what Roman and medieval scholars once called gesta (great deeds). Nonetheless, the form keeps a foothold inside the academy through single-authored accounts penned by prominent professors and through biographical megaprojects, including the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (a thorough revision and updating of its late nineteenth-century predecessor) and, closer to home, the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

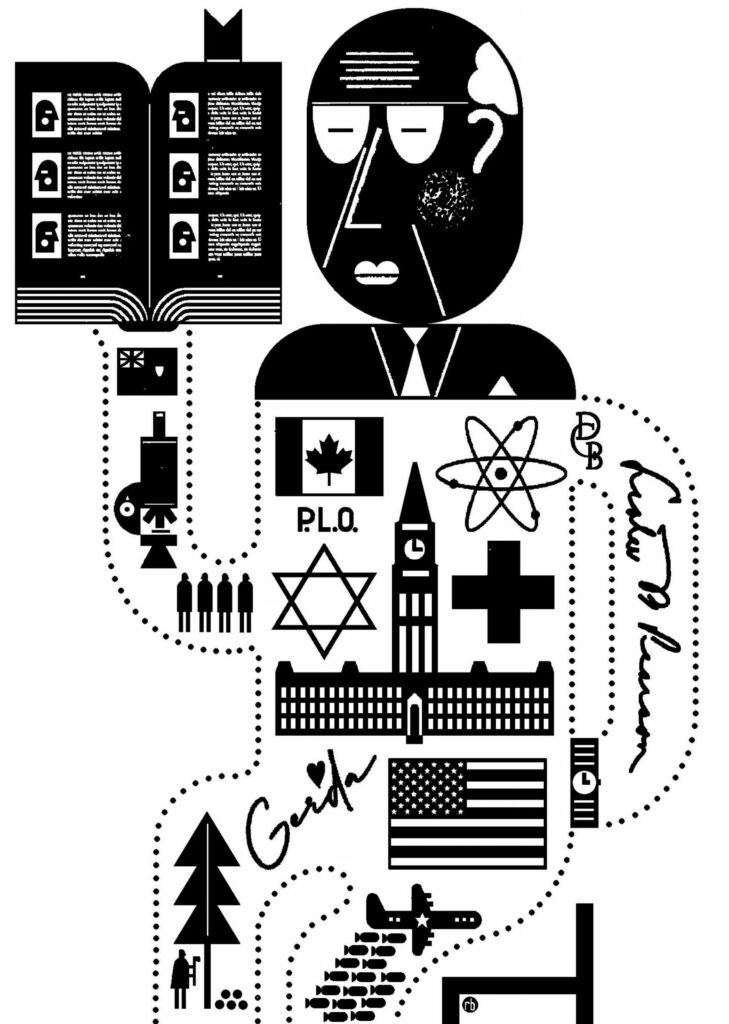

An entertaining political portrait.

Raymond Biesinger

Apart from the DCB and other online sources such as The Canadian Encyclopedia, classic biographies of major Canadian political figures, past and present, have come from authors such as Richard Gwyn (Sir John A. Macdonald) and John English (Lester B. Pearson and Pierre Elliott Trudeau). It is English, a former general editor of the DCB, who is honoured with a new collection of essays edited by Greg Donaghy and P. Whitney Lackenbauer. Bookended by a short foreword from Robert Bothwell of the University of Toronto and a conclusion by the historian and former Ontario cabinet minister John Milloy, who was encouraged by English as a graduate student, the book itself fits into a different genre of life writing altogether: People, Politics, and Purpose is a Festschrift, a celebration of an influential and accomplished academic, even if it lacks the “essays in honour of” subtitle that used to bill such volumes. (Contemporary marketers dissuade editors from the traditional practice for fear of limiting a collection’s appeal.)

As a genre, Festschriften, like other edited volumes, can lack the cohesiveness of biographies. At their worst, they can easily turn into miscellanies of unrelated chapters on widely differing topics, with no common theme and connected only by the accident of being authored by people who were once students or colleagues of the honouree. They are the Los Angeles of literary genres, with a few pleasant locales but no “there” there. Having co-edited two such works myself, I have every sympathy for editors trying to turn their assorted contributions into a whole that exceeds the sum of its parts.

The present volume is not immune from this problem, though the editors and authors have found connective tissue of sorts in foregrounding their subjects’ personal inclinations, preferences, and characters in discussions of wider political events. It’s all brought together with a rather bland, if alliterative, title (“people, politics, and purpose” doesn’t really narrow things down, but try saying it fast five times). The theme is outlined and the papers presented in a substantial introduction by the co-editors, one of whom (Donaghy) sadly died before the book was published.

The introduction is complemented by an opening chapter from Bothwell and Carleton University’s Norman Hillmer on the challenges of relying on “diplomatic autobiographers.” While in places a bit too much of a list of memoir writers, this essay exposes both the strengths and the limitations of memoirs and autobiographies as sources. Bothwell and Hillmer worry that there may be few successors to the likes of Pearson, Paul Martin Sr., and Paul Hellyer, as well as Donald Fleming, John Diefenbaker’s finance minister, whose autobiography was “surely the most pompous ever written by a Canadian politician,” and Marcel Cadieux, Martin’s undersecretary in External Affairs, whose “quasi-diary” indicates that he had mixed opinions about his political boss.

Unsurprisingly, given English’s own interests and career as a distinguished biographer and academic as well as a former member of Parliament, a number of the essays concern familiar political figures, including Pearson (who gets two chapters to himself and features in several others) and Diefenbaker (not the primary subject but a major actor in Lackenbauer’s excellent essay on the appointment of James Gladstone as Canada’s first Indigenous senator). Lesser-known persons also feature, including the notorious Gerda Munsinger. The star of Canada’s answer to Britain’s Profumo scandal (spies, Communists, politicians, and sex were involved in both cases), Munsinger was at the centre of an episode that did considerable damage to two successive governments, those of Diefenbaker and Pearson, as illustrated here by P. E. Bryden of the University of Victoria.

Two of the most interesting chapters shed light on influential politicians who never quite made it to the top: the canny Maritimer Allan MacEachen, who served as external affairs minister from 1974 to 1976 and again from 1982 to 1984, and Herb Gray, who was famously nicknamed “Gray Herb” because of his cultivated bland and low-key persona. Donaghy’s chapter on MacEachen explores his engagement with the Middle East at an especially tense juncture, including stickhandling relations with the Palestine Liberation Organization in the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The University of Toronto’s Jennifer Levin Bonder focuses her chapter on Gray, the first Jewish federal minister and a patient, long-serving MP, who was rather ruthlessly dumped from cabinet twice, by Trudeau in 1974 and by Jean Chrétien in 1997. But Gray’s popularity in his own riding of Windsor West is attested to by the southern Ontario parkway that now bears his name (with a “Right Honourable” prefix usually applied only to the prime minister, the governor general, and the chief justice) and by his continual re-election for four decades. He was one of the few survivors of the Turner government following Brian Mulroney’s 1984 landslide election win, but since Gray left politics in 2002, his former constituency has been held by the NDP.

The veteran diplomat John Hadwen’s experiences as high commissioner to India during the Joe Clark and Pierre Trudeau administrations are the subject of a fine chapter by Ryan Touhey, from the University of Waterloo, who ably demonstrates the impact that personality and personal history can have on politics. Hadwen’s deep foreign-service experience in India, dating back to the 1950s, as well as his recognition that trade is a crucial element in a diplomat’s tool kit, helped him to establish a good working relationship with New Delhi, including with the prickly prime minister Indira Gandhi (whose father, Jawaharlal Nehru, Hadwen admired). He kept up his efforts even during a time of high tension, following India’s nuclear testing in 1974 using Canadian technology. The fruits of Hadwen’s diplomacy included a resumption of high-profile visits by Canadian politicians, a considerable increase in trade, and — something for which every Canadian university is immensely thankful — the academic connections that have brought so many Indian students and faculty to our campuses over the past four decades.

Several chapters are heavily reliant on typical print sources, including government memoranda and published memoirs, but others delve deeper into the archives, notably Lackenbauer’s piece on Gladstone’s Senate appointment and Angelika Sauer’s essay on the “Lumberjack Wars” of the early 1940s. The former Texas Lutheran University professor uses non-traditional biographical sources to understand better the impacts of foreign and trade policy on ordinary fellas just trying to make a living (in this case, border-region woodsmen). As she puts it, the conflict may have been a tiny and short-lived tempest set against the background of America’s entry into the Second World War, but it was also a harbinger of testy commercial relations between the two countries in the postwar era and of a tendency for U.S. authorities, in Pearson’s words, “to consider us not as a foreign nation at all, but as one of themselves.”

Pearson’s own sometimes strained relations with his counterparts in Washington are explored in a chapter by Galen Roger Perras, of the University of Ottawa, and Asa McKercher, of the Royal Military College. Their memorable title, “That Bouncy Man,” comes from Dean Acheson, Harry Truman’s secretary of state and the child of Canadian parents. Our fourteenth prime minister’s reputation in Washington improved during his brief overlap, in 1963, with John F. Kennedy’s administration, but it deteriorated anew under the late president’s successor, when the Nobel laureate offended Lyndon B. Johnson by asking him to halt America’s bombing of North Vietnam. “Sometimes,” the authors conclude, “friends have to piss on someone’s rug.” The two leaders’ times in office were virtually coterminous, from 1963 to 1968, and, thankfully, Johnson got over his pique.

For all his various successes as a diplomat (nearly becoming the secretary-general of the United Nations) and cabinet sideman to William Lyon Mackenzie King (briefly) and Louis St-Laurent, Pearson’s own time in 24 Sussex has had mixed reviews from his biographers, at least according to Stephen Azzi, of Carleton University. In his view, Pearson was not nearly as ineffective a party leader as has sometimes been suggested (Jack Pickersgill, who served in cabinet, thought “Mike” a better opposition leader than prime minister) and his list of legislative achievements (with only a minority government through his five years in power) speaks for itself. Apart from the Canadian flag and our formal honours system, much of the social safety net we enjoy today, including the Canada Pension Plan and medicare, was indeed the product of Pearson’s tenure. The Just Society advocated by his longer-tenured and more charismatic successor Pierre Trudeau (much less the Justin Society being engineered by P. E. T.’s eldest child) would scarcely have been imaginable without the solid foundation laid by Pearson’s government. The same could be said of Canada’s prominent position as a middle power, which seems to have been taking a beating of late.

Readers of People, Politics, and Purpose will likely be academics — the book surely won’t make any holiday bestsellers list — but it is an entertaining and informative collection of portraits in Canadian leadership. In this way, it would be of interest to even non-specialists. Ultimately, it’s a worthy tribute to John English’s long and distinguished career within both the post-secondary and political worlds.

Daniel Woolf is a professor of history at Queen’s University, where he is also principal emeritus.