One of the features of mining is that it occurs mostly in places so remote from our increasingly urban landscapes as to be almost unimaginable. Massive operations blast and dig through bedrock the world over, from the mountainous, steaming jungles of New Guinea and the briny flats of South America to the frozen reaches of eastern Siberia. Out of sight, out of mind — and often beyond the reach of regulators.

In Pitfall: The Race to Mine the World’s Most Vulnerable Places, Christopher Pollon takes us to these uncommon places and argues that while humans need metals, we are “sleepwalking into the future,” failing to consider how the social and environmental costs of extraction are accelerating as we stoke our metal-dependent green-energy ambitions. The global South, in particular, is under pressure from a combination of poverty, corrupt leadership, China’s desire to control sources of such critical metals as cobalt and lithium, and twenty-first-century mining executives reaching ever further afield to find and develop new projects.

Canada does not escape Pollon’s scrutiny, particularly in his second chapter, “Nice People Behaving Badly.” While I would argue that we are generally good stewards of our own resources — because of our relatively stringent environmental and labour practices developed over centuries — we do not always transfer our high standards elsewhere. As Pollon writes, violence against mining opponents in Guatemala prompted a civil lawsuit against Vancouver-based Tahoe Resources, the former owner of the Escobal silver mine. In an unusual twist, the suit asked a court in Tahoe’s home jurisdiction — the Supreme Court of British Columbia — to declare the company responsible for injuries inflicted by security officers when they fired at farmers gathered to protest alleged pollution by the mine in 2013. Pan American Silver, the site’s current owner, eventually settled with the farmers and issued an apology.

Through Pollon, we meet the artisanal miners of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, displaced from their homes by industrial operations, gasping from cobalt dust as they scramble to feed the world’s growing appetite for smartphones and electric vehicles. We travel to the magnificent and lithium-rich Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia, where dreams of busting out of “five hundred years of resource servitude” by leveraging a valuable resource are fading as the government signs deals with Chinese partners eager to supply their own country’s EV battery and car industry. And we touch down in Indonesia, a country attempting to add value to its vast low-grade nickel reserves by creating battery-manufacturing hubs, a plan that threatens one of the most biodiverse areas on the planet.

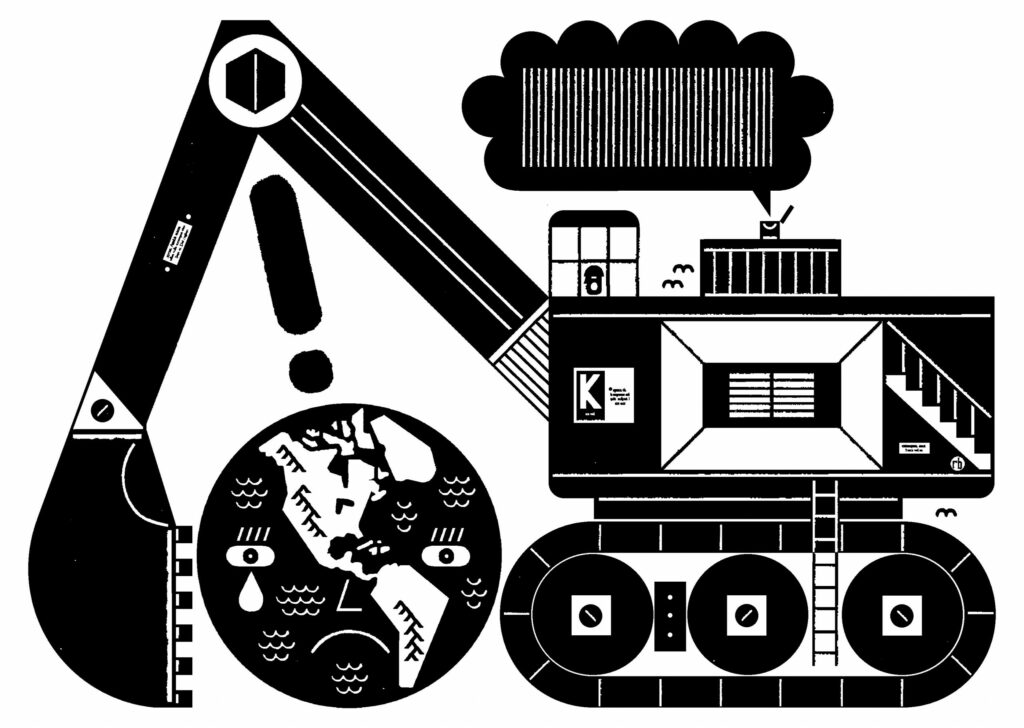

Considering possible future states of mined.

Raymond Biesinger

I look at mining through the lens of what humanity needs and not what global investors and metals markets demand — a subversive framing by design, which reflects the reality that industrial mining is in dire need of a paradigm-shifting disruption. Along the way, I identify what I refer to as “levers for change”— hopeful tools, ideas, and approaches that might lead us forward — as a way to provoke necessary conversations and action.

As Pollon researched Pitfall, industry representatives repeatedly instructed him to just “look around you” for an immediate understanding of the importance of metals in everyday life. But Pollon challenges the means by which the metals make their way from the earth’s crust into our laptops, smart watches, and electric cars. And he asks how far humankind is willing to go — to the bottom of the ocean? to far-flung asteroids? — to wean itself off fossil fuels.

There are three models of mining, none of them ideal. Artisanal mining is the informal and often hazardous activity that’s estimated to employ about 45 million people worldwide, some of them children. It is also “the biggest source of mercury pollution on the planet.” In industrial mining, publicly traded companies extract metals and sell them on the open market for profit, not always living up to the promise of improving the communities near their operations. (CEOs, after all, have a duty to extract the maximum possible return on investment for shareholders.) State-owned entities such as Corporación Nacional del Cobre de Chile, which operates seven industrial mines, form a third category. Codelco has created enormous wealth for Chileans by mining a significant portion of the world’s copper, but it is facing a scarcity of water that threatens not only local agriculture but the thirsty mining operations themselves.

Pollon is at his best when describing the cast of characters exploiting the world’s metal riches. Mobutu Sese Seko, the former dictator of what would become the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was “a totalitarian in a leopard-skin hat, who . . . treated his country’s national resources as his own private ATM.” Marc Rich, known as one of the pioneers of modern commodity trading, is “an enabler for despots, Russian oligarchs, and rogue factions with resources to sell.” Robert Friedland, now one of the world’s wealthiest men thanks to his knack for targeting highly profitable mineral deposits, is “a wily stock promoter from the Wild West days of the Vancouver Stock Exchange.” And Gerard Barron, the “long-haired, leather-jacketed” CEO of The Metals Company, based in Vancouver, looks and sounds “more like Bono than a mining executive” as he brands himself as a climate saviour with his proposal to search the ocean floor for battery metals.

Pollon’s research is thorough and wide reaching, but it lacks examples of mines that have won a social licence to operate by improving lives in nearby communities. They do exist. (The Éléonore gold mine in Northern Quebec — where the Cree Nation secured an agreement for training, employment, and business opportunities that integrates traditional knowledge into the facility’s environmental management process — comes to mind.) Nonetheless, he weaves some fascinating scenes and anecdotes into his book. At the state-owned Chuquicamata mine in Chile, one of the biggest copper mines in the world, he sees wind turbines and solar arrays towering above open pits to help supply the huge amounts of power the operation requires. The irony that it took millions of tonnes of iron and aluminum ore and massive amounts of fossil fuels to manufacture and erect these renewable energy sources is not lost on him. To highlight the hard limits on how deep we can go, he takes us back to 1972 in Oklahoma, where exploration came to an abrupt halt, about ten kilometres down, when a drill bit hit molten sulphur. And at a massive “urban mine” in suburban Vancouver, he observes workers hand-sorting scrap scavenged from airplanes, army tanks, and railcars to be recycled into reusable metal, one of his more positive glimpses into the future.

Ideally, that future will include much more recycling, as legislation, already being enacted in China and the European Union, forces companies to recoup the metals in spent electronics and EV batteries. And perhaps mining can become a service — the industry’s version of Uber — in which community-owned mines call on specialist expertise to extract their ore but reap the benefits as locals see fit. This kind of mining would flip the traditional economy-of‑scale model on its head, though it’s difficult to imagine how it would work in remote locations, where the costs of mining and transporting ore require huge injections of capital.

Using the example of the quick and dramatic reduction in U.S. consumption during the Second World War, as citizens joined forces to conserve resources, Pollon argues that solving the environmental and social problems created by our voracious appetite for minerals “is not a question of technology, or innovation, as much as it is a matter of motivation: as recent history demonstrates, all it takes to spur the change the world needs is a credible threat.” That credible threat is here in the floods, record heat, and unprecedented wildfires the world experienced in the summer of 2023. It will take international leadership to spur the change.

Virginia Heffernan wrote Ring of Fire: High-Stakes Mining in a Lowlands Wilderness.