Who knew? That one of the greatest spies before the Second World War was a Canadian? That one of MI6’s stalwart assets had been a champion debater at Mount Allison University, in Sackville, New Brunswick? That this master of the espionage arts wrote the school’s “Alma Mater Song”? That after playing Hamlet, serving as class president, and graduating as valedictorian in 1904, he went on to study philosophy in the university town of Göttingen, Germany? And that he was one of the first to recognize that the upheaval in that country in the wake of the First World War threatened to unsettle all of Europe and could lead to something like the Nazi tragedy?

Who knew? Almost nobody until now — until Jason Bell, a philosophy professor at the University of New Brunswick, spent fifteen years conducting interviews, rummaging through archives, and examining formerly classified papers to recreate the life of a man named Winthrop Bell (no relation to the author), known in the shadowy world of British spydom as A12. He was, according to Cracking the Nazi Code, “quite possibly history’s greatest spy” and “the first intelligence agent to warn about the National Socialists and their plan for the Second World War.” What’s more, Winthrop Bell “helped ensure that Adolf Hitler lost World War II.”

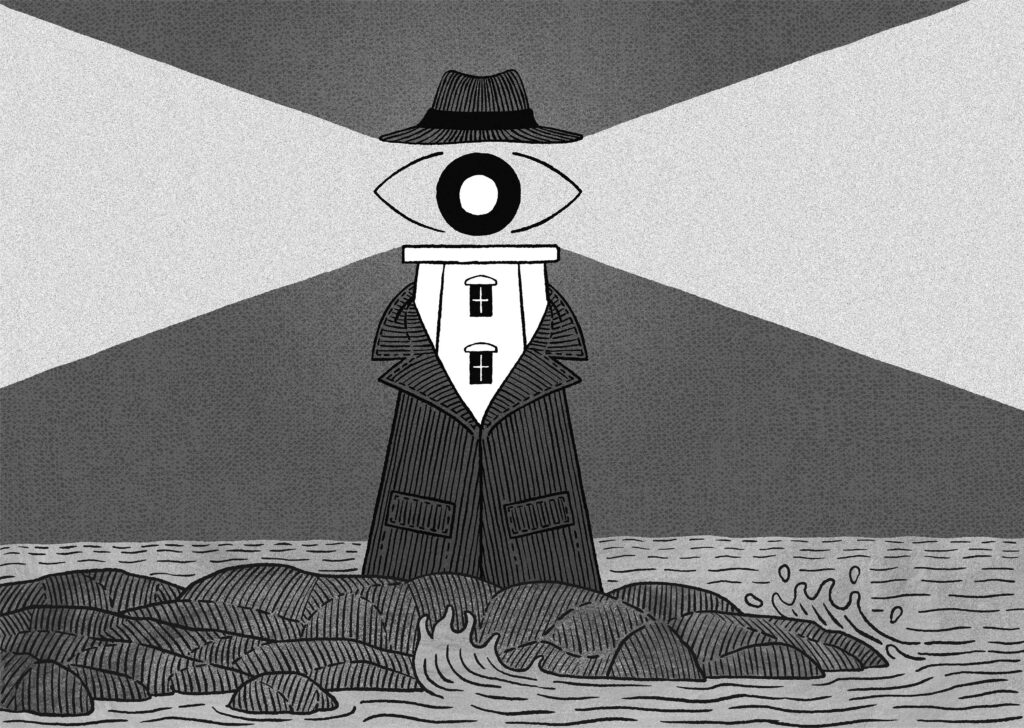

The beacon of British intelligence known as A12 was actually one of us.

Tom Chitty

He may have worked for the British, may have been a British subject, but Winthrop Bell was also Canadian to the core. Born in Halifax in 1884, he spent time as a railroad surveyor; was family friends with Canada’s eighth prime minister, Robert Borden; was determined, later in life, to build the Royal Canadian Air Force into a robust fighting unit; and used his final years to write about early Nova Scotia history. All that is prelude and coda to a career in the penumbra of espionage, much of it conducted under the cover of being a Reuters correspondent, just one of the identities — scholar, businessman, genealogist, among many others — that he assumed and that he pursued with diligence and excellence.

How could such a figure — tall, muscular, and blond — remain so hidden? That, of course, is the way of espionage, and especially the way of A12, whom the author characterizes as “completely inconspicuous, and yet right there all the time.” He had a sharp eye, a fine mind, and excellent judgment. Through his university friends, he had access to Germany’s secret military cyphers. And with connections to Borden and others, he drifted into British intelligence circles. Such a passage is never a straight line or a path with right angles, and Bell’s certainly wasn’t. He may not have possessed photographic memory, but he had an even better asset: he could see around the corners of history. Thus he could anticipate the future — and all that was not going to work.

The author tells us — this may be hyperbole, for it is unprovable — that Winthrop Bell was the first to understand the power of the German alliance between postwar racists, nationalists, and socialists. These were the ties that would lead to the formation of the Nazi party. At the urging of Borden — whose twin ambitions were to help to shape a world that would allow Canada to flourish and to win latitude from London by providing it with vital intelligence — Bell briefed top officials about the crisis in mainland Europe in late 1918. It was clear that, as the author puts it, “his knowledge made him ideally positioned to become Britain’s newest secret agent.”

There’s sufficient derring‑do in this volume to qualify it as a spy story — enough history to serve as a serviceable introduction to interwar Europe, enough scholarship to satisfy the faculty lounge, whose denizens often look upon commercial success with both contempt and envy. This tale is told with care and nuance, without the overplaying embellishment that sometimes comes with stories of this nature. The author follows A12 as he becomes deeply embedded in Britain’s spy world and in spycraft itself, all the while setting out his subject’s understanding of the various complex (and often, to contemporary readers, confusing) strains of rebellion inside the Weimar Republic and more broadly across Europe. He makes clear, moreover, A12’s comprehension of how privation and politics combined to create a toxic mix in a devastated land and among desperate people, hungry for food and for security alike.

Superior analytic skills were not enough for A12 — nor for any spy. He needed to acquire the kit and the skills of espionage, and that required instruction in making and breaking code, maintaining cover, communicating his findings back to headquarters, cultivating and protecting sources, and the various ways to use a weapon. These were certainly not the skills imparted at Göttingen. But before long he was reporting on the relationship between German nationalists and the Russian antisemites who were murdering Jews in Ukraine. “For Bell, the job was personal,” the author writes. “Germany’s democrats, some of them Jews, were his closest friends. He would do everything in his power, including risking his life, to protect them from the extremists who had committed widespread acts of violence.”

Winthrop Bell pursued much of his work in the guise of a reporter. “Thwarting the militant racists in a shadow propaganda war would require ink by the barrelful,” the author writes. “The Reuters job gave it to him, in grand style, with access to millions of English-speaking newspaper readers across the globe.” It was anything but a simple arrangement: “It appears that Canada supplied a line of funding that covered Bell’s salary through the Bank of Montreal. MI6 covered his travelling expenses and the cost of his top-secret telegraphs. And Reuters covered the cost of his journalistic telegraphs.”

There is a long history, repellent to genuine journalists, of reporters being recruited for spy work and of spies employing the cover of the reporter’s trade to perform their craft. There is a long history, too — consider, for example, the practice of the United States Central Intelligence Agency — of debriefing correspondents returning from crisis areas or seconded to hostile countries. Just a friendly session for midday tea and conversation, mind you, perhaps sharing an innocent preprandial dry sherry. Such correspondents, commonly bewildered about the balance between their ethical codes and their patriotic responsibilities to their home governments, have often been willing to share their insights. As a result, there is an equally long history, also repellent to genuine journalists, of national leaders, primarily in paranoid dictatorships (and here you will forgive the redundancy), suspecting journalists of pursuing espionage. That is why the Wall Street Journal correspondent Evan Gershkovich was detained in Vladimir Putin’s Russia on March 29, 2023, and charged, without evidence, with being a spy.

But truth to tell — and I tell this regretfully — A12 had as a journalist more access to informed sources and intelligence than he might have had as a garden-variety double agent (with apologies to Giorgio Bassani) in the garden of the Finzi-Continis or (with apologies to Erik Larson) in the garden of beasts. And in this role, he uncovered for his spymaster the development of plots to import Communist revolution to Germany, even as nationalists were sowing antisemitic sentiments, planning a race war, and setting in motion forces that would lead to another world war. Bell was an exceptional reporter and thus an exceptional spy. “He alone,” the author tells us, perhaps with a pinch of overstatement, “was in a position to fight a single-handed intelligence war against the powerful, ruthless men who would soon become the Nazis.”

Bell had, for instance, special insights about the Freikorps, discovering that, like their counterparts on the left, the volunteer irregulars often were more interested in food and money than in extremist ideology. That is largely forgotten today. No Marxist himself, Bell nonetheless understood the connection between economic forces and politics — between the price of milk in Munich and the rise of the Nazis, as historians in the 1970s would later put it. One sentence he sent from Germany in 1919 captures such insight: “The question of the daily bread is no merely theoretical one.” Like John Maynard Keynes, he understood the link between German reparations and German deprivation. He conspired with Albert Einstein to provide food for starving people. Even so, Berlin was convulsed by insurrection. Bell reported:

While Death swings his scythe, and recurring influenza epidemics sweep away the youngest and strongest, the people waste its money in tawdry pleasures, and seeks only distraction. Wild political ideas intoxicate the few of the best that are still left of the youth of the country, with the illusion of a movement of spiritual life.

Germany was on the verge of Communist revolution when A12 was summoned to brief the British Parliament on the dire and deteriorating situation. He predicted that the country could soon be consumed with tension and violence between rightists and leftists and, ultimately, might be controlled by extremists of one tint or another. That was prescient but incomplete. Soon he came to the conclusion that the enemy of groups on both the right and left wasn’t the other so much as it was liberal democracy itself and that the two forces could be merged into an even greater menace. As the author explains,

Bell knew that before [Baron von] Schenck’s spring 1919 matchmaking, the nationalists and the socialists were less like oil and water that could not mix and more like sodium and water that exploded when they touched. When they had been at each other’s throats, each weakened the other, and German democracy stayed in the driver’s seat. United, the terrorists outgunned the democrats. Yet they were still no match for the Allies, so they kept themselves secret.

The particulars of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919, only exacerbated the situation. A12 speculated that Germany could become the “perpetual pariah” of Europe and warned that “only if the population can see a prospect of food and endurable livelihood under the conditions imposed, can we count on internal peace and ordered production here.” These were the economic consequences of the peace, as Keynes would describe them the following year.

Another flashpoint was the lovely city of Danzig, defined as independent by the treaty but claimed by Germany and coveted by Poland. A12 circled about as the diplomats at the peace table conceived of a place neither German nor Polish. Good luck with that. The tussle over Danzig would help shape geopolitics for several years, but A12 understood right away how the emerging Nazis, who had been “tremendously disappointed” by the negotiations surrounding it, threatened Europe’s peace and the continent’s Jews. It was a threat that could not easily be contained: “Bell had discovered the reactionaries’ secret. They were now fighting the next stage of the Great War, the nakedly racial part. He knew their weaknesses, and how to destroy them.”

Much of A12’s prophecy was suppressed by London, a tragedy in real time and nearly incomprehensible in retrospect. He understood that the British and the Allies were too weak, too wary, too weary, too conflict-averse, and too blind to heed him; besides, they, like the Germans, were too divided. Nobody in the democracies wanted another fight, a return to the trenches. Nobody had a taste (in the mordant but significant phrase long associated with Oxford) for fighting for king and country — or, for that matter, for president and country. The price of listening was too great. The price of turning a deaf ear would turn out to be far greater.

A12 abandoned his alias in February 1920 and retreated as Winthrop Bell to the University of Toronto, then to Harvard, and finally to the Maritimes. But retirement from the world he once knew was not forever. By 1939, he would be warning, again, of the threat that the Nazis posed to Europe and to decency and, more broadly, to humankind itself. The philosopher, after all, had a master’s degree in history, and in the pages of Saturday Night he produced what may have been “the most important article the newsweekly ever published, and one of the most important that any journal has ever published.” The tragedy is that too few listened to “the first publication, by years, to warn against the Nazis’ plan for worldwide genocide.”

So in the end we ask the question: Who knew? Many more should have.

Six decades ago, audiences on both sides of the Atlantic flocked to a period piece called Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, a madcap romp set in 1910 that starred, among many others, Red Skelton and Stuart Whitman. Cold War over Canada is a more serious account of later magnificent men in their RCAF flying machines. At its centre is one officer, E. Scott Maclagan, a navigator aboard all-weather jet interceptors like the two-seat Avro Canada CF‑100 Canuck.

Maclagan’s charming book takes readers from his days at Orillia District Collegiate and Vocational Institute, in Ontario, where he became an expert marksman with the Royal Canadian Army Cadets; to the summer he spent working as milkman and his student years at Ryerson Institute of Technology in the mid‑1950s; to his time guiding injured aircraft and clueless aviators to safety (no easy task, requiring a kind of rendezvous in the air); and to various other episodes in which he helped preserve national security — or would have, had the Soviets actually decided to strike.

“Every scramble order meant we were going up after an unknown that could be a Soviet bomber attacking North America, or an aircraft that had failed to file a flight plan, or one that had veered significantly off course,” he writes. “Often it would turn out to be a Strategic Air Command or British bomber testing our reaction time without previously warning anyone.”

The view from 45,000 feet — including memories of live‑fire exercises at Cold Lake, Alberta, and of worrying whether the various targets Maclagan helped track down might be Soviet Tu‑95 “Bear” long-range bombers — makes for an engaging read. Aspects of this career certainly sound thrilling, but, as Maclagan writes, it was also “a very unsettling way to live.” Nonetheless, this Cold War flyer helped provide safety for Canada in aircraft that we might no longer regard as safe. To which we say not only thank you for your service, but also thank you for your book.

David Marks Shribman teaches in the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He won a Pulitzer Prize for beat reporting in 1995.