The twentieth century, it is safe to say, has made all of us into deep historical pessimists.

— Francis FukuyamaIt’s the end of the world as we know it

And I feel fine.

— R.E.M.

Does anyone else feel, against their better judgment, a slight twinge of nostalgia for the 1990s, after the Berlin Wall came down and the internet came into our homes? It is possible, after all, to feel longing for ages that weren’t exactly golden, especially if the one you are experiencing is filled with uncertainty and dread. This is shown in Good Bye, Lenin!, Wolfgang Becker’s film from 2003, in which a young man recreates the conditions of the recently defunct German Democratic Republic in his family’s Berlin apartment, in order to soothe his mother’s heart condition when she awakes from the coma she slipped into before everything changed. Ironically, their place becomes a haven for their nostalgic neighbours, who find themselves adrift in the baffling world of consumer capitalism and European integration unleashed by the end of Communism.

A quarter of the way into the twenty-first century, against the backdrop of war in Ukraine and Gaza, the rise of the far right, the migrant crisis, increasing economic inequality, and the looming threat of climate catastrophe, it is quite possible to feel a wistful pull for the bland security of the late twentieth century. As an era, the ’90s shine because they came before so many distasteful realities hove into view. At the very least, they are the last epoch of the recent past when the term “troll farm” suggested merely Nordic folklore.

Of course, the ’90s were also when Francis Fukuyama famously declared the “end of history.” With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the collapse of the Soviet Union two years later, the ideological and geopolitical schism that had defined so much of the century was over. The West had won. History itself — that is, history understood in the grand manner as the dialectical conflict between such polarized forces as slaves and masters, peoples and kings, Communists and capitalists — was coming to a close. In the words of Margaret Thatcher, there was “no alternative” to liberal democratic government and free market economics.

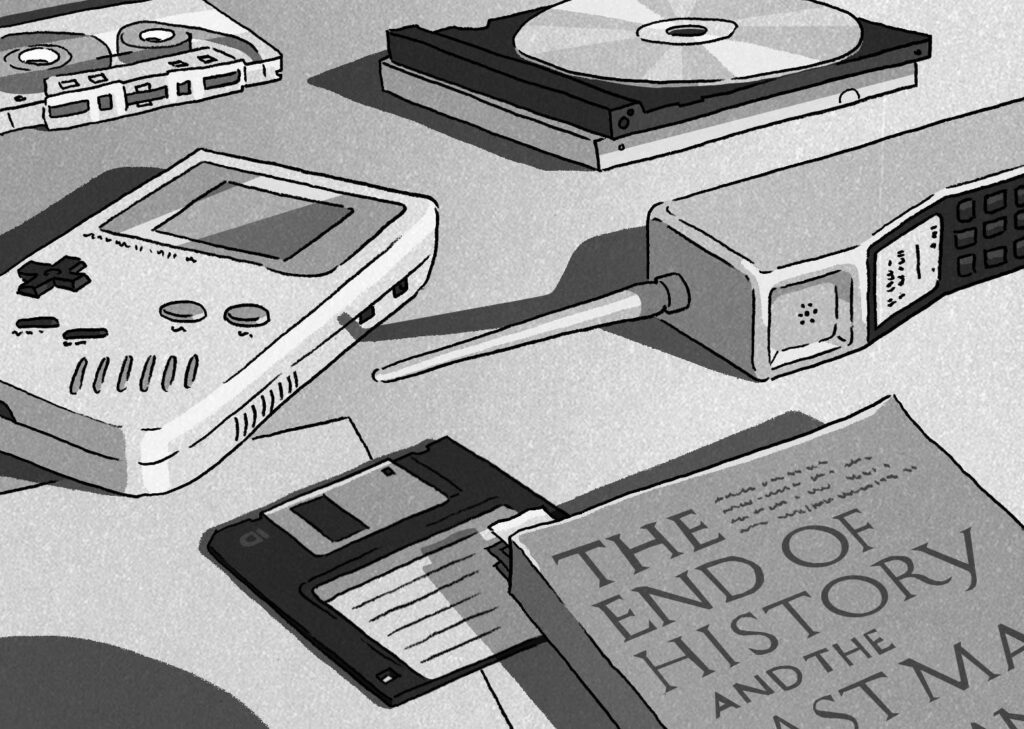

Longing for an age that wasn’t exactly golden.

Tim Bouckley

Thatcher had used that phrase —“there is no alternative”— as a cudgel with which to beat her political opponents in the ’80s. By the early ’90s, however, it was taken by many as a simple geopolitical reality. The neo-liberal “shock therapy” that was administered to the centrally planned economies of former Soviet satellites was convulsive in the extreme, but at the time few commentators foresaw the rise of Vladimir Putin or the klepto-oligarchic imperialist petro-state that Russia would become. On the other side of the world, China responded to the tumultuous events of 1989 by accelerating its own transition toward consumer capitalism. At its 1992 National Congress, the Chinese Communist Party announced its commitment to a “socialist market economy,” and by late 2001 it was a fully paid‑up member of the World Trade Organization. At the time, the Western commentariat confidently predicted that the Chinese state would eventually introduce democratic reforms to accompany its free market system. These pundits tend to be much less sanguine today.

In the 1990s, centrist politicians like Bill Clinton cast free market globalization as “the economic equivalent of a force of nature, like wind or water.” A whole new web of transnational institutions, highly technocratic and barely accountable to national electorates, was formed to administer world trade. In 1992, the Maastricht Treaty ushered in the new European Union, creating the largest free trade area on earth. In 1993, Clinton relied on the votes of Republican lawmakers to ratify the North American Free Trade Agreement. In 1995, the WTO was formed, and the anti-capitalist protests at its meeting in Seattle in 1999 made for an exciting spectacle on the nightly news. But no one — least of all the protesters themselves, who favoured carnivalesque street performances over direct pressure via the mechanisms of state power — took them as a meaningful threat to the new global order.

Fukuyama was not simply describing a contingent set of conditions within world affairs. His argument was more ambitious — much more ambitious — than that. According to his theory, the events of 1989 and 1991 were the culmination of a rational process that was woven into the very fabric of human history. Democracy and free market economics weren’t just the least bad systems available, to paraphrase Winston Churchill; they were expressions of the fundamental properties of human nature, as discovered through the slow march of historical progress.

In this respect, Fukuyama was intervening in a long-running debate between the heavyweights of nineteenth-century German political philosophy, Karl Marx and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Of these two giants, he claimed, it was Hegel who had got things right. The arc of history bent not toward a Marxist utopia, as the revolutionaries of 1917 had believed, but toward the bourgeois liberal nation-state, a kind of permanent European Union of the soul. Hegel claimed to have seen this historical destiny embodied in the all-conquering figure of Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle of Jena in 1806, famously dubbing him “the world spirit on horseback.” For Hegel and his followers, this was the beginning of the end of history, the point at which the philosophical achievements of the Enlightenment — the universal rights of man — were detached from the bloody turmoil of the French Revolution and enshrined in the durable form of the rational state. Neither Hegel nor Fukuyama claimed that there would be no more historical events. There would still be wars and politics, palace coups and popular uprisings, religious movements and scientific discoveries, but these events would all unfold against a settled backdrop of political theory, which enshrined freedom and equal rights as the necessary conditions of political order.

The other plank of Fukuyama’s construct was the fundamental human need for recognition, a concept with a long lineage in Western philosophy. In Plato’s Republic, the key term is thymos, which is usually translated as “spiritedness” and forms the third essential part of human nature alongside the more familiar concepts logos and eros. Like reason and passion, thymos must be properly managed to ensure social harmony. Unchecked, it leads to domination and exploitation. Tyrants demand not simply more power and wealth than their subjects but also excessive forms of recognition. Hence the giant palaces and bad public art erected by the likes of Joseph Stalin and Nicolae Ceaușescu to monopolize their underlings’ attention; hence the needlessly provocative tweets of Elon Musk, who cannot be satisfied unless his status is also validated by millions of eyeballs on X. But Fukuyama also recognized the importance of thymos in the plight of social minorities who seek recognition in the eyes of the state. The campaigns for women’s, Black, Indigenous, LGBTQ, and disability rights all emanate from the thymotic desire for recognition by our peers. This is why, according to Fukuyama, liberal democracy constitutes the rational end point of human history, as it is the only form of government that grants equal recognition to every citizen.

Fukuyama’s wide-ranging proposition is apt to make The End of History and the Last Man sound like a work of Western liberal triumphalism, which is precisely how many readers interpreted it. Critics on the left, for example, accused the author of simply casting the political ideology of American capitalism in universalist language. For a brief time at the end of the 1990s, Fukuyama threw in his lot with the Project for the New American Century, the neo-conservative think tank that provided the ideological blueprint for the second Gulf War and George W. Bush’s misbegotten attempt to spread American-style democracy in the Middle East. But Fukuyama was always a more complex thinker than either his critics or supporters tended to recognize. Notably, he stressed that there were more ways to organize a market economy than the American consensus allowed for. As he moved away from the neo‑cons, Fukuyama increasingly aligned himself with Denmark’s social democratic model of regulated capitalism — not the libertarian one found in Texas.

Fukuyama was no simple booster for “freedom” and “capitalism” in the tedious sense so familiar to viewers of Fox News. The phrase “the end of history” has come to denote a cultural mood as much as a political theory, what Hegel might have called the zeitgeist of the ’90s. Indeed, The End of History and the Last Man is shot through with melancholy descriptions of the post-historical scene. Consumerist anomie and spiritual nihilism were now the dominant moods. When all of the big questions of government and society seemed to have been resolved, civic life lost much of its relish. The great political passions that once animated the breasts of men and women had dwindled and dimmed. An empty formalism had crept into the culture, as the avant-garde breakthroughs of the past gave way to stasis and repetition.

So much of ’90s popular culture was defined by a sense of sped‑up purposelessness and hedonistic resignation. The mumbling apathy of grunge and slacker culture, the narcotic escapism of rave music, the nihilistic entrepreneurialism of gangsta rap, the postmodern irony of Quentin Tarantino movies: these were all expressions of what it was like to live in an era in which there was no alternative to consumer capitalism, when the best we could do was to retreat into subcultural niches or ironic gestures of pre-commodified dissent. This is why nostalgia for the decade is doubly ambivalent. All nostalgia is a fantastical idealization of the past, but ’90s nostalgia is an idealization of a past that was already soaked in nostalgia, already highly aware of its own alienation.

During the halcyon days of the internet, the only really compelling vision of an alternative future emanated from the digital realm, where “jacking in” and “logging on” were cast as edgy ways of making contact with a sci‑fi hereafter that was in the process of being born. With their predictions of virtual reality telecommuting and digital democracy, the tech gurus at the MIT Media Lab and Wired magazine peddled a vision of social transformation via the super-abundant wealth of networks. One of the few genuinely trailblazing movements of the ’90s was commerce itself, the free jazz of high finance and cyber-bluster that inflated the dot‑com bubble as investors scrambled to own a slice of tomorrow. But the world that was being built turned out to be simply an enhanced version of the post-historical present: seamless, personalized, networked, and user-friendly on the surface but with the whirring machinery of libertarian turbo-capitalism under the hood. In July 1997, Wired proclaimed the advent of the “long boom,” during which the digital revolution would power unbroken economic growth for the foreseeable future. “We’re facing 25 years of prosperity, freedom, and a better environment for the whole world. You got a problem with that?” bellowed its cover. Read it and weep.

As we look back from today, Fukuyama’s dream of the end of history seems like a curio from another age. As every sentient human with an internet connection is aware, world politics has become increasingly turbulent in recent years. American unipolar dominance is badly frayed, if not entirely threadbare; it lasted roughly until the 2010s, or the amount of time it took for Washington to pour trillions of dollars into a series of unwinnable foreign wars, while Beijing spent roughly the same amount on its Belt and Road Initiative throughout Asia and Africa. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s excursions into Taiwanese airspace presage a new multipolar reality.

The great financial crisis of 2008 pulled the rug out from under the neo-liberal consensus of the preceding thirty-odd years. As governments bailed out the banks and passed the costs on to citizens in the form of fiscal austerity, the rigged game of global capitalism was made plain for all to see. We have been living with the ramifications ever since in the form of widespread distrust of civic institutions and the rise of both right- and left-wing populisms.

So much that was blithely accepted as settled has been thrown into question once again. This has been an era of mass protest: the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, Idle No More, Black Lives Matter, the Yellow Vests, Extinction Rebellion, and student encampments have all brought politics back to the streets. Challenges to centrist orthodoxy have emerged throughout world affairs, from the traction Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn found in America and Britain to the authoritarian populisms of Donald Trump, Viktor Orbán, and Jair Bolsonaro.

But this kind of analysis makes the recent past seem too orderly, too readily amenable to neat op‑ed-style narratives. So much of everyday life in the twenty-first century has taken on a feverish, even bizarro tinge. We’ve seen a reality TV star in the White House, the mainstreaming of conspiracy theories (from progressive fantasies about Russian kompromat to conservative paranoia about vaccines and pets in Ohio), freak weather patterns and a biosphere breakdown, mass quarantine and state-mandated mothballing of entire sectors of the economy, an angry mob encouraged to invade the U.S. Capitol by an outgoing president, and angry truckers blockading Parliament Hill and threatening to execute the prime minister. Norms have been busted, expectations scrambled. The Overton window — the measure of how long it takes on average for a fringe idea to make its way into the political mainstream — has been itself thrown out of the window.

It seems as though the end of history has itself come to an end. This is the argument made by Alex Hochuli, George Hoare, and Philip Cunliffe in The End of the End of History, from 2021. As they put it, the great financial crash of 2008 created the material conditions for the end of the end of history; the Brexit referendum and Trump’s election victory in 2016 announced its arrival in the political sphere; and the lockdowns and related derangements of the pandemic made it definitive. Crucially, though, their analysis comes with a major caveat: just because the end of history is at an end, it doesn’t mean that the political struggles of the pre‑1989 world — a world that was shaped by mass political parties, the organized working class, and radical alternatives to the status quo — have been brought back to life.

The constituencies that drove mass politics for much of the second half of the twentieth century have been transformed beyond all recognition. As we exit from the end of history, we find ourselves in a political landscape in which large swaths of the working class no longer vote for the old social democratic parties, and equally large swaths of what Thomas Piketty calls the Brahmin Left (educated, affluent, progressive, intersectional) prefer moralizing about identity politics to allyship with the “traditional,” which is to say white, provincial, uneducated working class. Even as the neo-liberal consensus frays, mainstream politics keeps on serving up the unappetizing choice between bland technocrats and populist frauds. In place of a potential new politics of inequality, we get posturing blowhards and endless culture wars.

Checkmate against Fukuyama, then? Well, maybe check, but certainly not mate. In fact, some of the most intriguing sections of The End of History and the Last Man are the ones in which Fukuyama speculated on the possible conditions that might bring about the end of the end of history, not least because they foreshadowed much of what is happening today. Even back in the triumphalist atmosphere of the early ’90s, Fukuyama recognized that the principal threat to liberalism is economic inequality. He predicted that any future alternative to liberal democracy would emerge either from “those who for cultural reasons experience persistent economic failure” or from “those who are inordinately successful at the capitalist game”— what we would today call the economically “left behind” and the global billionaire class. These two groups exist at the radical edges of the liberal order because they have the most to gain from its discontinuation. They have already proven fertile ground for post-liberal, even anti-democratic political ideas, from far‑right authoritarianism to the secessionist fantasies of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, who dream of a purer, more heroic form of capitalism in their offshore enclaves and future Martian colonies.

Another potential threat is sheer boredom at the conditions of existence within bourgeois consumer societies. The basic conditions of life for the vast majority of citizens in the affluent West remain unchanged: we work, we shop, we eat, we sleep, and occasionally we cast a vote for one of the parties that operate within the narrow bandwidth of mainstream political ideology. The mechanisms of liberal democracy afford relatively weak forms of recognition, which leave a large reservoir of surplus thymos circulating within the population. These urges can be expressed in a variety of benign ways, from volunteering at your local soup kitchen to training to climb Mount Everest. They can also take less savoury forms, such as the clamour for recognition by celebrity activists, alt‑right provocateurs, and self-appointed “influencers” in the ceaseless churn of social media. Thymos is the double-edged source of both our capacity for self-transcending acts of heroism and our capacity for affront and offence, grudge and grumble. All too often, political life at the end of history caters only to the latter half of our thymotic natures: our narrow sectional identities and petty resentments.

Since the publication of his surprise bestseller, Fukuyama has revised parts of his argument, but he has never jettisoned the basic theoretical framework. In a recent Financial Times op‑ed, for instance, he contended that the prospect of another Trump presidency should be met with a concerted process of institutional reform (in particular, of campaign finance, the electoral college, and political primaries), but he did not cast the Republican nominee as an existential threat to democracy itself nor as a refutation of his core thesis about the end of history. While there may be much still to recommend Fukuyama’s theories, his policy provisions, while sensible, seem rather milquetoast in relation to the deep corrosion of civic life in recent years.

If we look beyond the brief span of time between the fall of the Berlin Wall and our own age of anxiety, we see that history has ended several times before. We also see that those endings themselves came to an end. Hegel understood Napoleon’s victory at Jena as the end of history, but so too did Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky interpret the Bolshevik Revolution as the beginning of the end of a historical trajectory that led from czarist serfdom to the abolition of the class society. Alexandre Kojève, whose lectures on Hegel at the Sorbonne in the 1930s (published in 1947) were a major influence on Fukuyama, cast the postwar formation of the European Economic Community as another “end of history” moment, a restatement of Hegel’s original thesis but in a new set of institutional arrangements that charted a middle way between the twin excesses of American capitalism and Soviet Communism. In 1960, the American sociologist Daniel Bell declared the “end of ideology,” maintaining that mass prosperity and civil rights had extinguished the grand political ideologies of prior epochs. Each of these supposed endings presented a different answer to the abiding questions of human freedom and recognition.

When he formulated his theory, Fukuyama glossed over a central ambiguity in Kojève’s definition of freedom. The French philosopher saw the end of history as encompassing two potentially contradictory concepts of freedom. The first was the freedom of the marketplace, as expressed in the equivalence of values in the cash nexus and the liberty to buy and sell as one chooses. The second was the freedom of the polis, or the equal rights of all citizens in the eyes of the democratic state. Postwar social democracy was the political system that emerged in order to balance those two forms of freedom. Since 1989, it has all too often been economic freedom that has dominated. This makes any potential exit from the end of the end of history all the more difficult, as it requires us to go against the grain of entrenched orthodoxy, which casts freedom in highly individualistic and economic terms.

“It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.” This phrase has become something of a refrain in cultural criticism. Popularized by the blogger and academic Mark Fisher, it highlights the disparity between the dystopian fantasies of contemporary popular culture and the narrow ideological range of mainstream politics. If the ironic postures of Kurt Cobain and Quentin Tarantino characterized the ’90s, then it is the apocalyptic catastrophism of The Road, The Hunger Games, The Walking Dead, and their ilk that captures the mood of the twenty-first century. But while our own era might seem turbulent and chaotic, it is also a moment of significant opportunity as the excesses of neo-liberalism are laid bare for all to see. Perhaps, as the century reaches its second quarter, our biggest challenge is to imagine a future that is neither boring nor catastrophic but merely better than the present.

James Brooke-Smith is a literary critic and cultural historian at the University of Ottawa. His September 2019 piece for the magazine, “Meritocracy and Its Discontents,” was included in Best Canadian Essays 2020.