National anthems are tricky things. As enforced relics of a previous age, they’re a bad fit for an enlightened era that doesn’t feel the need to conform to an older generation’s invented traditions. Words offend, ideologies become outmoded, regimes change, friends morph into enemies, native lands turn into contested domains, patriotic death is seen as a waste of life, and what some out-of-touch composers and flattered rulers once considered the best tunes for rallying a reluctant nation become, in David Pate’s arresting phrase, the worst songs in the world.

There are many degrees of worseness in modern music — and national anthems are a surprisingly modern invention, starting with an impromptu “God Save the King” in 1745, picking up speed with the nationalistic movements of the nineteenth century, and becoming a definitive global phenomenon only in the twentieth century as dozens of independent states emerged from the rubble of anthem-defined, potentate-led empires and then settled the score, so to speak. For each new cohort, the cringeworthy music of our younger years only gets worse when replayed incessantly in dental offices and liquor stores and during gloomy public-television fundraisers. Compared with an endless diet of saccharine pop hits, the anthems passed down through the ages and mouthed repetitively from childhood can feel more like comfort food, the musical equivalent of Grandma’s apple pie.

Originality is rarely a virtue in the crafting of a national anthem.

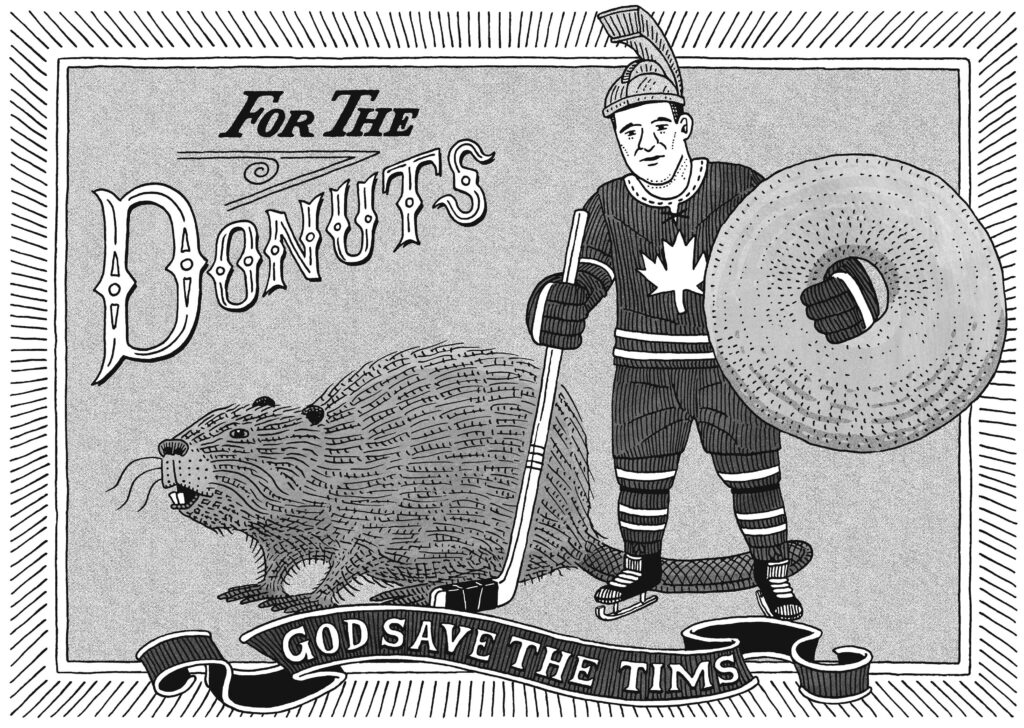

Tom Chitty

But the critical difference with anthems is that we’re asked, and in many countries told and admonished by officialdom, to become a part of them. The sounds of antiquated marches and hymns and royal salutes and ripped-off arias and purloined drinking songs emanate from within your own rigidly upright body, as your individual distinctions and choices are muted amid an off-key crowd singing an anthem that may or may not represent your musical or philosophical ideals. The object of all that collective crooning — a crown, a flag, an idea of a nation worthier in the abstract than in day-to-day particulars, a call to arms, a defeated enemy on a bloody battlefield, or a glorious death, depending on the vagaries of history — is almost certainly out of step with modern, democratic, peace-loving, trouble-avoiding sensibilities. We’re stuck with someone else’s idea of who we are and who we want to be. And on the off chance that the anthem monitors are watching us as closely and critically as they scrutinize insufficiently proud athletes on playing fields and podiums, we’re expected to stand on guard and sing out the words with true patriot love, whatever that means now.

So far, so bad. The creation of an anthem on which so much of our national identity rests can be unexpectedly random, as Pate points out. The music for Malaysia’s anthem, one fanciful story goes, descends from a tune supplied by an aide to the sultan of Perak during an 1888 visit to London in honour of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. (Others suggest a later visit for Edward VII’s coronation.) The band set to welcome the sultan was instructed to play his land’s equivalent of “Hail to the Chief”— brassy military tributes being an essential perk for powerful leaders — and since there was not yet any such thing, the unprepared aide whistled a popular song called “Bright Moon,” which transcribers quickly arranged for a diplomatically appropriate welcome.

When Perak was folded into the federation that ultimately became Malaysia, a competition for a new anthem was announced; a national song was seen as a necessary precondition of independent statehood. After poring over hundreds of submissions, including entries from Benjamin Britten and William Walton (veteran practitioners from the British school of special-occasion tunesmithing), the judges fell back on the much more hummable local folk tune — which was actually a popular Indonesian number tracing its improbable beginnings to the Seychelles, where the sultan had spent years in not uncomfortable exile.

But when it comes to the inventive originality of quickly composed anthems, sometimes it’s better not to inquire too far. The challenging music for “The Star-Spangled Banner,” with its one-and-a-half-octave vocal range, is based on an old English drinking song. (Some critics, given the inept renditions performed by over-refreshed sports-stadium soloists, consider the tune the original sobriety test.) If you find yourself absent-mindedly humming “O Canada” while listening to “March of the Priests” from Mozart’s The Magic Flute, keep in mind that Calixa Lavallée was working to an impossibly tight deadline and not writing for the ages when he composed his stirring version of a national march for the 1880 Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day celebrations.

For the short leap from an instant to an enduring composition, it’s hard to beat “God Save the King.” The prototype of the national anthem was introduced at London’s Drury Lane Theatre one Saturday night in 1745 as an afterthought to a production of Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist. This reassuring expression of fealty to George II, based on an existing melody and familiar lyrics, was arranged by Thomas Arne. He also composed the much more rousing “Rule, Britannia!,” which continues to be an over-the-top singalong number (“Britons never, never, never will be slaves”) at the BBC’s populist Last Night of the Proms concert and is preferred by many as an alternative to the dour anthem. “God bless our noble King,” as the first version of “God Save the King” put it, has priority on its side and certainly passed the genuflecting loyalty test of those troubled times, when the Jacobite forces were on the march in Scotland and proclaiming Bonnie Prince Charlie the true sovereign. But as a vehicle for collective carousing that just as easily might have equated patriotism with self-affirmation, happiness, and even fun, Arne’s dirge-like tribute definitely wasn’t the best model for anthems to come.

Originality isn’t a virtue in anthem making. The simple, repetitive, devotional rhythms of “God Save the King” (itself an amalgam of traditional melodies) became the standard for other nations’ patriotic songs, including imperial Russia’s “The Prayer of the Russians,” Norway’s royal anthem, little Liechtenstein’s “High on the Young Rhine” (“Where the chamois leaps freely / The eagle soars boldly,” like a Rhenish “Home on the Range”), the original Swiss anthem, the American classic “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” and Prussia’s “Hail to Thee in the Victor’s Crown,” which a unified Germany chose as its anthem in 1871, with the unintended consequence that British and German troops in the First World War pledged their patriotic fervour and marched deathwards to exactly the same tune.

This wouldn’t do. European anthems had become as inbred as their royalty — unsurprisingly, given that the original king whom God was implored to bless at the Drury Lane Theatre was German born, after all. But what does it mean to be an independent people if you don’t have a song to call your own? And this is where the history of a seemingly straightforward thing like an anthem becomes especially murky and troublesome. “Das Lied der Deutschen” may not have been the worst song in the world, at least in the beginning. Its infamous opening lines —“Deutschland, Deutschland über alles / Über alles in der Welt”— as much as they sounded like an especially aggressive battle song in the tradition of, say, “La Marseillaise,” could be construed by charitable historians as a preference for national unity over divisive loyalties to local princelings. The melody had a respectable pedigree, which is a polite way of saying that it was borrowed in that complimentary anthemic style from neighbouring Austria. The celebrated composer Joseph Haydn wrote the original music to honour the Hapsburg emperor Franz II, closely following the formula of the genre-establishing “God Save the King.” But the association of those lyrics with Nazi Germany’s murderous mantra of Aryan superiority tainted them irredeemably. East Germany devised a new anthem in the postwar era fittingly titled “Risen from Ruins,” which lost traction in the 1970s as Communist ambitions waned before it was finally abandoned upon reunification. “And that’s a pity,” writes Pate, “because it’s a great tune and would have been a good choice for a unified Germany.”

West Germany, created in 1949, opted for a return to the traditional music of “Das Lied der Deutschen” after several years of hesitation, so powerful is the lure of the familiar when it comes to a national song. But the opening stanza’s connection to Nazism forced a shift to the more benign third verse, with its anodyne championing of unity, justice, and freedom. (The postwar reconstructors carefully bypassed the second verse, with its chauvinistic praise of German women — and wine — but still anachronistically compelled the ladies in the crowd to sing of brotherly striving in the best interests of the fatherland.) Predictably, unapologetic German rightists have been campaigning for years to restore the more triumphant, belligerent first verse.

Anthems at first glance seem unalterable, the national version of Holy Writ, the sung-aloud pride of identity rooted in tradition, respect, stability, and generational continuity. The modern idea of a nation, with its promises of shared governance, participatory decision making, and social mobility, is a fragile construct that challenged the established hierarchy and unquestioned rule of absolute authority: old-style autocrats hardly needed reassuring songs performed by the people to remind themselves that they were in full control, that they were adored beyond all measure. But as power decentralized, boundaries fluctuated, people mixed and migrated, and commonality could no longer be enforced or assumed, these songs became an essential part of the artifice in bringing disparate individuals and conflicting values together under one flag. It’s no wonder victorious national teams and proudly sung anthems are such a potent patriotic combination, echoing George Orwell’s comment that sport is “war minus the shooting.”

However much politicians like to adhere to the if-it-ain’t-broken-don’t-fix-it rule book of leadership, anthems change all the time. Necessity is the strongest motivator. Those de-nazifying West Germany had no choice but to cut ties with “über alles,” even as they held on to the Haydn tune appropriated from their neighbour. Austria, which lost its lyrics along with its independence when it was annexed into the Third Reich in 1938, clearly needed a do‑over after the Second World War. Haydn’s music had acquired a bad odour by association with the Nazis. (Even some West German leaders wanted to ditch the tune, though they were overruled by their first chancellor, Konrad Adenauer.) Austria’s new national song, despite its lyrics being written by a woman, was still a creature of its time and its genre and arrived replete with references to sons and brothers and a fatherland, all of which took another six decades to change — though, as Pate notes, tradition-loving Austrians, of whom there are many, refuse to honour the updated gender-inclusive version, turning a symbol of national unity into an emblem of political disagreement. Faced with a similar issue in Germany, ever-pragmatic, don’t-overthink-it Angela Merkel brushed off the foes of the word “Vaterland” by saying simply that she didn’t see any reason to fuss with it.

Of course, there’s a powerful external motivation for change, even if it’s not perceived as a pressing political need — just listen to the voices of the people clamouring for it. “Aux armes, citoyens,” as one of the original revolutionary anthems puts it, is a defiant reminder that there is more than one way to hymn a country and champion an ideal. Why be so wedded to archaic language of exclusivity, the orthodoxy of a different world, when an anthem is meant to unify and inspire rather than divide and deny?

The devil-you-know attitude has its merits in the fractious political realm, where proposing to tamper with the traditional and familiar is the equivalent of stirring up toxic sediment or removing old asbestos. Observed from afar, it’s easy to make suggestions for other people’s anthems: the Dutch, for example, have many good reasons to renovate their national song, starting with its outlandish premise. The lyrics, which schoolchildren are expected to learn, constitute a first-person statement by the sixteenth-century leader William of Nassau, who starts out pledging lifelong loyalty to the king of Spain (for various arcane Hapsburgian reasons) but who eventually, over many verses, comes round to the cause of Dutch independence.

The only adequate defence for the song, apart from its marginal relevance as a cultural artifact and teaching tool, is that it is almost impossible for the average modern-day singer to care too deeply about what they, in the guise of William of Nassau, are singing. Did I mention that the original fifteen verses are written in the form of an acrostic that playfully spells out William of Nassau’s name? This has proven too much for the Dutch, who have chosen to limit their patriotic confusion by singing only the first verse and, occasionally, the sixth. Even if uncritical deference to the status quo is an innate characteristic of most anthems and those who love them, the fact of the matter is that, as The Worst Songs in the World illustrates, anthems can and do and, frequently, must adapt.

Many older anthems are ridiculously long for modern audiences and have been pruned back to the point of being little more than jingles. Where’s the outcry from anthem originalists that the Dutch people, by singing just a single verse, are ruining a good acrostic? Global bodies like the Fédération Internationale de Football Association and the International Olympic Committee are major patrons of anthem culture (despite the founder of the modern Games, Pierre de Coubertin, wishing that nationalism be kept at a safe distance). Both incorporate a larger anthem-playing membership than the United Nations and normalize abbreviated versions by mandating playable recordings that are no longer than ninety seconds (FIFA) or eighty (IOC). “God Save the King,” “O Canada” (in French and English), “La Marseillaise,” the 158 verses of the original Greek national hymn, and almost every fine old anthem you could name have been truncated to TikTok length to suit the limited patience of busier times — to say nothing of modern sensibilities that aren’t eager to salute “stalwart sons and gentle maidens” while awaiting the Resurrection (“O Canada,” English version) or to repeat the conquering cry “For Christ and the King” while submitting to the yoke of faith (“O Canada,” French version).

Abridgement is the rule, not the exception, and the only regret may be how rarely we get to hear sweet-voiced British choristers sing these memorable lines, addressed to their God, asking for maltreatment of the monarch’s enemies: “Confound their politics / Frustrate their knavish tricks.” “The Star-Spangled Banner” (which wasn’t proclaimed the national anthem of the United States until 1931 as a cheery Depression mood-lifter) does go on a bit, especially when mangled by note-prolonging narcissists making the musical case against American exceptionalism. But there are three verses (one including an unwelcome reference to slavery) that fell by the wayside, which would have delayed ceremonial F‑16 flyovers and glorious opening kickoffs even further. Not even the most diehard flag-wavers are crying out for their return.

We may lament the short attention span of our scattered contemporaries, but in this case they have it exactly right. The language in the extended versions is often mystifyingly specific about old wars and enemies ad infinitum and offensive to modern ears as a matter of course. The original Greek national hymn included a roll call of bad guys and an itemizing of carcasses that simply don’t fit the decorum of international diplomacy — especially when the song is played at the end of every Olympic Games. (Organizers usually go with the instrumental version, just to be safe.) South American countries that won their independence from Spain had a natural tendency to exact verbal vengeance against their oppressor through their post-colonial songs; nothing inspires revolutionary anthems, stirs up their singers, and justifies lyrics that proclaim the longing for a glorious death like a tyrannical overlord. But times change, and economic factors trump ancient hatreds; as early as 1900, Argentina’s president was trying to smooth things over with the old enemy by paring anti-Spanish verses and explaining, “The national hymn contains phrases written for another era which over time have lost their contemporary relevance.” See — it’s not that hard.

But of course it is. Take Canada. Like many countries once aligned with the British Empire, we have had a two-track problem with the altering of our anthem: first, finding a more representative one, and second, making it fit our vague and ever-changing national values. “God Save the Queen,” championed by Conservative anglophones, lingered surprisingly long and, despite nationalist protests at venues like the monarchist Conn Smythe’s Maple Leaf Gardens, was still being sung in public schools in the 1960s. It was not until 1980 that “O Canada” was declared our official anthem, a century after the French version was composed. It took another thirty-eight years of intense linguistic reflection to alter “in all thy sons command”— that troublesome line from the early twentieth-century English version — to “in all of us command.” God, the intrusive protector and defender beloved by traditional anthem authors, was absent from the first verse of the long-accepted English version but managed to sneak in thanks to a 1968 parliamentary committee’s rewording, on the pretext of deleting a superfluous “We stand on guard.” And there the omnipotent power remains, a divisive presence in a diverse country, keeping us glorious and free but ever more reluctant to sing someone else’s misbegotten theocratic words.

Meanwhile, we still need to confront “our home and native land,” an awkward, exclusionary phrase for a country that has been dependent on immigration for so much of its history. “Our home and/or native land” doesn’t quite have the right lyrical ring. In 1991, Toronto’s city council proposed “home and cherished land,” which is an improvement but a bit too greeting-card bland and difficult to sing. Then at the 2023 National Basketball Association All‑Star Game in Salt Lake City, the R&B singer Jully Black used the troublesome word in a different sense by changing the line to “our home on native land.” (I imagine that David Pate, who sadly died before The Worst Songs in the World was published, would have understood this gesture and even appreciated it.)

Pate makes it clear where he’s coming from in his criticisms of anthems. As a young boy at a Scottish boarding school, he was beaten for not singing “God Save the Queen,” an anthem for an English head of state rooted in anti-Scottish sentiment. How, he wondered, could his loyalty be inculcated through corporal punishment and compulsory singing? He learned to subvert authority, while saving his skin, by mouthing the words instead of intoning them. Most of us who take issue with the lyrics of our anthem, or the overenthusiastic gusto with which it’s sung by people who consider themselves the truest of patriots, similarly learn the value of playing along by not drawing attention to our disagreements. It’s not very noble and certainly not the best expression of personal liberty, but when they tell you to rise, you rise.

One can understand why official anthem changers move slowly and almost too carefully. Consider the anger that ensued when a member of the Tenors quartet went off script at the 2016 Major League Baseball All‑Star Game, amid Black Lives Matter protests, and dropped two lines of the French version of “O Canada,” replacing them with the dismissively contentious words “We’re all brothers and sisters / All lives matter to the great.” If anyone can change the lyrics at will, there is no national anthem, just individual statements and group protests. And thus anthems begin to lose their point. Perhaps a country like the United States with its many possible national songs (“America the Beautiful,” “My Country, ’Tis of Thee,” “God Bless America,” “This Land Is Your Land,” “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “We Shall Overcome,” “Lift Every Voice and Sing”) is better off with this multiplicity of choices, however imperfect, especially when they’re easier to sing than the authorized paean.

Other anthems often look more attractive than our own, in large part because we can savour them as beguiling music full of fundamental human emotion rather than as sources of conflict. Why does the defiant singing of “La Marseillaise” (with a problematic reference to impure blood watering French fields) so readily move us non-French viewers of Casablanca to tears? Who can forget their surprise and amazement at hearing the first notes of the wordless Soviet anthem at the beginning of the 1972 Canada-U.S.S.R. hockey series: “That is one powerful song!” The crowd in Montreal, including Pierre Trudeau en boutonnière, erupted into applause when the music ended. A degree of detachment can be liberating: if the performing of a patriotic melody was more like a campfire singsong or Christmas carolling or school choiring or even (may the God of anthems help us) Pitch Perfect a cappella showboating, we wouldn’t have to commit to the content quite so wholeheartedly, while still savouring the certifiably good-for-you pleasure of singing together.

Just such a pleasure was experienced en masse at, of all places, a Toronto Maple Leafs game in 2014. The Nashville Predators were in town, and as the young anthem singer began her task, her microphone faltered. She restarted with a new mic, and once again she couldn’t be heard. Silence. And then the crowd picked up the tune, and before long thousands of people were singing together, quite beautifully, doing their best to rescue and console the soloist but also enjoying the unexpected thrill that singing together can still provide.

The weird and wonderful part of that spontaneous occasion was that Toronto hockey fans were singing not “O Canada” but “The Star-Spangled Banner,” articulating the complex lyrics without missing a beat and even hitting the high notes respectably — the choral equivalent of the wisdom of the crowd. Watching videos of the performance, which has been replicated in other Canadian arenas to the point that it’s become a tradition, and reading comments from grateful Americans on social media, it’s hard to believe that anthems bring out the bad in us, that they deserve to be labelled the worst songs. If singing someone else’s anthem can be such a glorious experience, why shouldn’t we be able to find good feelings in our own?

John Allemang can do a word-perfect rendition of “God Save the King” in Latin — just ask.