Nicholas Flood Davin, who covered the execution of Louis Riel in November 1885 for the Regina Leader, observed, “Nothing in his life so became him as the leaving of it.” Davin, otherwise unsympathetic to Riel and his cause, was apparently so impressed by the courage with which the condemned man met his early death, at the age of forty-one, that only lines from a Shakespearean tragedy (Macbeth) could do justice to the moment. Death was itself Riel’s last great expressive act, compelling the admiration even of his enemies. For his supporters, it was the heroic death of a martyr, even a saint. For the legion of scholars who have written about him since, it has served, conveniently, as the dramatic end point of an otherwise uncertain narrative full of twists and turns. In a strange way, it clarifies. Throughout the century and a half since his execution, there might be little consensus about what to call Louis Riel — traitor to Canada, victim of British or Canadian imperialism, heretic, saint, madman, prophet, democratic defender of the rights of the oppressed, would‑be theocrat, opportunist, unrecognized father of Confederation — but the manner in which he faced his end speaks for itself.

It was perhaps with this assessment in mind that the French historian Jean Meyer chose to begin Louis Riel: Prophète du Nouveau Monde with a detailed account of the death. He evokes striking images: Riel, calmly taking the initiative at dawn when his jailer is too overcome to speak, saying to him in English, “Mister Gibson, do you want me? I am ready.” Riel consoling his sobbing confessor, Father André, this time in French: “Courage, mon père!” The hangman, an Ontario Orangeman, an old enemy of Riel’s from the Manitoba upheaval, whispering to the prisoner, “Do you recognize me? Today you won’t escape me.” Riel reciting, again in English, the Lord’s Prayer, the trap door opening by prearrangement, after the words “but deliver us.”

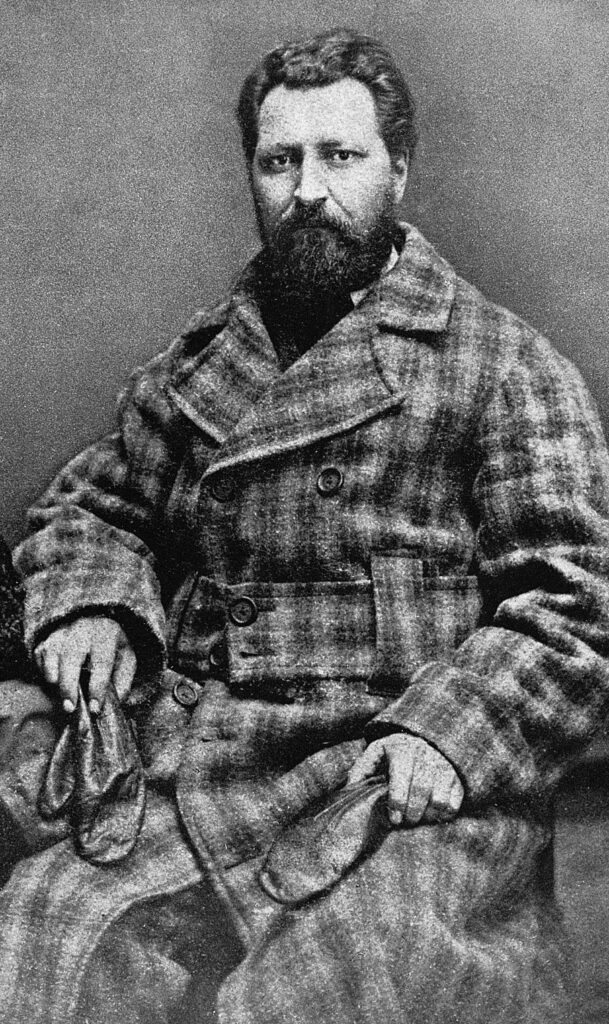

Riel in Keeseville, New York, in early 1878.

Granger Historical Picture Archive; Alamy

The launch of Meyer’s book in Canada last spring was planned to coincide with the cinematic release of Louis Riel ou Le Ciel touche la terre (Louis Riel or Heaven touches the earth), directed by the author’s son, Matias Meyer, about Riel’s final eight days. The Métis actor from Manitoba originally hired for the part suddenly withdrew, fearing that he would be attacked for acting in a film directed by a non-Métis. Ironically, as a journalist pointed out in Le Devoir, Meyer happens to be the son of a French father and a Mexican mother of Indigenous origin. Undeterred by Canadian cancel culture, Matias Meyer himself played Riel.

Meyer père first stumbled upon Riel in 1964 while a twenty-two-year-old studying history in Paris under the supervision of Georges Duby, an influential member of the Annales school of French historians. Some reading about the British Empire in one of the Cambridge Histories introduced him to the man, and from that point his focus became Canada from 1812 to 1914. After graduation and long detours into Mexican and Russian history, he came back to his original fascination with Riel, and the result, sixty years later, is this first major study of the Métis leader to appear in French for a long time. At eighty-two, Meyer has finally made his own contribution to what he calls “la Rieliade” (by his own count, some 767 works distributed among 2,476 publications in three languages, including biographies, academic histories, journals, memoirs, literary media, and some 13,800 internet entries). He observes that the contemporary fascination with Riel is a phenomenon more characteristic of anglophone Canada than of Quebec. Riel, as a Métis from western Canada and adamantly Catholic, does not much excite a province that is anticlerical and largely indifferent to what is not itself, including francophones elsewhere in the country.

Given the massive growth of the Rieliade since Meyer first encountered the Métis leader, does he really have anything new to say? This question was uppermost as I faced the prospect of reading this very long book in French, especially when the author declares in his prologue that he will be following the all too well trodden path of casting Riel as the hero of his narrative and the victim of Sir John A. Macdonald’s obsession with completing a railroad across Canada. Meyer also makes it clear that his many hours in various archives consulting the documentary sources and his reading of almost all the significant secondary literature in French and English have not yielded anything startlingly original concerning the details of his subject’s life, thought, political activities, and death. As he acknowledges with disarming honesty: “I am perched on the shoulders of my predecessors. . . . I haven’t read everything, but I’ve read to the point that I won’t be able to avoid involuntary appropriations.”

The question of originality aside, there are aspects of Meyer’s book that make it stand apart in compelling ways. His opening of the historical narrative by focusing on Riel’s death is followed in the next chapter with an equally unusual personal account of his own encounters with Riel, which finally brought him to the North-West (Manitoba and Saskatchewan), where he, a European, felt in himself “the weight of its history, the force of its life.” Meyer breathes life into the past by frequent resort to imagined dialogue among his protagonists, in defiance of the stricter style of academic history (and in a way similar to Chester Brown’s remarkably effective graphic novel about Riel). Meyer justifies these ventures into imagined dialogue by invoking the defence formulated by his maître, Duby, of the scholar’s right to imagine, so long as it is done within the limits of what is knowable, remains truthful, and forbids itself any anachronism.

Meyer certainly demonstrates an awareness of the way in which the personage of Riel exposes so many of the fissures of Canada, past and present: French and English, Indigenous and settler, Catholic and Protestant, West and East, rural and urban, the legality and the violence at the source of the Canadian state. But what I found most compelling in his approach is that he lifts Riel out of the usual in‑house Canadian discourse and makes of him an international figure. As a European, Meyer necessarily comes at Riel from outside Canada. The publication of the book itself testifies to this; it is a translation into French from the Spanish in which it was originally written, its publisher is based in Paris, and the preface is by the French novelist and Nobel laureate J. M. G. Le Clézio. Meyer’s treatment of Riel follows his numerous works on Mexican history, most notably La Cristiada, about the Cristero rebellion of the 1920s (also the subject of a film by Matias Meyer), and the mid-nineteenth-century War of Reform led by Manuel Lozada. In this latest account, Riel’s movement among the Métis of Manitoba, then Saskatchewan, becomes part of a more widespread Indigenous resistance to the intersecting and competing imperialisms of Britain, France, Spain, and the United States.

This larger perspective was shared by Riel himself, who prophesied, in his last diary entry, that Latin America would lend “a strong hand to the Greater Pontificate in . . . Manitoba.” Indeed, a timeline provided by Meyer points to a yet more global dynamic involving Africa and Asia. To offer a sample of events occurring just before, during, or after the Red River and Saskatchewan Resistances: the American Civil War and subsequent expansionism of the victorious North, the purchase of Alaska from Russia by the U.S., Canadian Confederation, the defeat of France by Prussia, the Maori uprising in New Zealand, the Kabyle uprising in Algeria, Russian conquests in central Asia, French conquests in Indochina, the division of large chunks of Africa among the European colonial powers, the Muslim revolt against Britain in the Sudan and the Mahdi’s capture of Khartoum, the driving of the last spike on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Events outside Canada were, moreover, known and taken into account by those involved in the Canadian story. As his diaries indicate, Riel looked to the South American resistance movements; he also met with Ulysses S. Grant, president of the newly unified U.S., and was not above slyly playing off the American imperial threat against central Canadian expansionist aspirations in the North-West. Macdonald, for his part, was well aware that British fear of growing German power after the defeat of France meant that London was eager for good relations with Washington and would be quite willing to make concessions at Canada’s expense. The prime minister was also dealing with pressure from the British to support their military venture in the Sudan. One might wonder to what extent Macdonald’s intransigence toward Riel was explicable by a sincere belief in his own rhetoric about the man being a “kind of Métis Mahdi.” And Meyer notes that Riel’s trial and sentence became an international event, with newspapers in France, Ireland, the U.S., and even England urging clemency.

Meyer’s determination to place Riel within a larger-than-Canadian context sometimes stretches plausibility. Louis Riel and Manuel Lozada seems insightful; Riel and John Brown of Harper’s Ferry fame, worth pursuing. But Riel and Joan of Arc? Perhaps — insofar as both led movements of armed resistance that were as much religious as political, or more so, and both were declared heretics by their own churches. In Meyer’s words: “He was not slow in coming to the realization, like Joan of Arc, that ‘the people of the Church are not the Church.’ ”

The extra-Canadian connection I found most intriguing was that of Riel and Prince Myshkin of Dostoevsky’s novel The Idiot (published just months before the start of the Red River Resistance). Myshkin, like Riel, is in some ways a stranger to his own roots, since he has spent his formative years outside Russia. Riel spent his in Montreal, studying at a Sulpician college with a view to becoming a priest. Each then returned to his native land, driven by a sense of mission to help it become what it ought to be. Myshkin is generally a gentle, Christ-like character, who nevertheless becomes remarkably agitated, even fiercely so, when he begins to hold forth on the subject of Russian destiny in the face of the homogenizing power of modern Western capitalism and scientific rationalism. Possessing that rare gift of charisma, he is able to hold his audience spellbound. Ultimately, however, his mission can be deemed a failure, and the novel ends with his descent into madness and return to an asylum in Switzerland.

Riel, too, might be considered a prophetic figure; he certainly thought so, styling himself repeatedly as the Prophet of the New World and the Métis as a people chosen by God. His prophethood, too, was connected with his “madness.” Meyer insists that in order to assess both, one must listen to Riel himself. His words are enough to fill five volumes of his Collected Writings: speeches, memoranda, manifestos, poetry, correspondence, and diaries. And together with the words there was a charisma attested to by contemporaries who witnessed the moments of exaltation when “he was not the same man. His blazing gaze, the timbre of his voice, the turbulence of his thick head of hair, all gave him a frightening aspect, and his entire person manifested eloquence.”

The prophetic eloquence of a “word warrior,” to use the scholar Dale Turner’s phrase, was both his weapon and his downfall. It made him a leader of the Métis people of the North-West, who sought him out as the one who could give voice to their sufferings and aspirations. Sometimes he used the language of liberal rights, in its American republican and, more frequently, British constitutional modes. When doing so, he could be effective in hoisting on its own petard what he called “la Puissance” (the Power) in Ottawa and London. Decades later, his role in the Red River Resistance (1869–70), which led to the creation of the province of Manitoba, earned him a statue on the grounds of the Manitoba Legislative Building and a status close to being a father of Confederation. When leaders of the later Métis resistance (1885) in Saskatchewan sought him out in his American exile, they hoped that he would again be their effective voice against the political and economic power that threatened their way of life. They discovered, however, that Riel’s prophetic voice had become more exclusively religious in its language since the Red River days. Even Gabriel Dumont, the commander of the Métis forces who revered Riel, began to lose patience with this prophet who came to defend their rights but spoke only of religion. Meyer refers to Dumont’s later testimony that at one crucial point in the days leading to the disaster at the Battle of Batoche, in May 1885, he had the better plan, “humanly speaking,” but was overruled by Riel’s “confidence in his faith and in his prayers.” The voice that had once appealed with effect to the traditional rights of the subjects of the Crown now appealed increasingly to the Book of Revelation. The Riel of the Red River Resistance had become Louis “David” Riel, the Prophet of the New World, rider of the “white horse of the Apocalypse.” This development seems to have been precipitated by two events, both in 1875: a visionary experience while in Washington (of all places) and the receipt of a letter from Ignace Bourget, the bishop of Montreal, which Riel interpreted as a commission from God that he must serve for the “honour of religion.”

The details of Riel’s prophetic visions, as expressed in his own words, are available in writings such as “Révélation de la Sublime Porte” (Revelation of the High Gate, referring to the court of the Ottoman Empire) and “Révélations se rapportant aux nations de la terre” (Revelations relating to the nations of the earth) and throughout his diaries. They do contain some shrewd insights into future geopolitics: for instance, that the new German nation will become an empire to be reckoned with, that the United States is destined to inherit the power and prosperity then possessed by Great Britain — all of this couched in obscure and wild symbolism. According to Meyer, the writings revolve primarily around the notion that the Roman Catholic pontificate has “fallen”— it was in 1870 that the new Italian state took over the papal territories, confining the angry Pius IX to Vatican City — and its spiritual power is passing from an old and tired Europe to the younger New World, more specifically to the Catholic Métis nation of the North-West. Riel was the prophet of this final epoch of the Kingdom of God, to whom the Holy Spirit spoke directly. What the Spirit was telling him was that the Holy See of the Roman Catholic Church, the longest-living organized spiritual institution in world history, was passing from Europe to Canada: first to Montreal, where Ignace Bourget was bishop, and then to St. Boniface, Manitoba. This ambitious prophecy promised, to put it mildly, to thrust Canada onto the international main stage.

It hardly needs saying that in today’s intellectual world, close examination of Riel’s prophetic writings does not invite much interest. One of the few scholars who have done Riel the courtesy of carefully reading rather than simply ignoring his religious thought is Thomas Flanagan, whose Louis “David” Riel situates the Prophet of the New World within the larger context of a Catholic millenarianism originating with the twelfth-century Calabrian monk Joachim of Fiore, who envisaged a future consummation of history in an imminent new age of freedom and plenitude: the epoch of the Holy Spirit, succeeding the epochs of the Father (Judaism) and the Son (the Roman Catholic Church).

This tripartite theology of history was declared heretical, but Joachim’s medieval contemporaries did not consider him a madman. Riel, on the other hand, was confined to an asylum in Quebec for two years (1876–78). His contemporary Karl Marx, also a messianic thinker, enjoyed quite a different fate, partly because he succeeded in transposing Joachimism into a secular philosophical scheme.

It was primarily Riel’s words that led to the asylum, as they were to lead him eventually to the scaffold. Was Riel mad? The diagnosis of the asylum doctor was “megalomania,” which in its dictionary meaning of “delusions of grandeur” is not much help in assessing prophetic religious figures who, in conformity with the original Greek etymology of the word (pro‑phetes), “speak for” God. Under the influence of Michel Foucault’s analysis of the modern asylum in Madness and Civilization, we have learned to be wary of a hard and fast distinction between the “world of madness” and the “world of reason,” especially where this reason seems to reflect little more than bourgeois morality. During his trial, Riel himself never accepted his own lawyer’s strategy of a defence according to insanity. This was one respect in which there was agreement between him and his old enemy Macdonald, who would not commute Riel’s sentence on this basis. Meyer, for his part, also disputes the notion of Riel’s madness, because an adequate interpretation of his mental state belongs not to the domain of medicine or law but to theology. If this is the case, then the term “heretic,” applied to Riel by his own church, might be more appropriate.

While he indignantly rejected the assessment of insanity urged by the asylum doctor and then by his defence counsel, Riel was finally willing to accept the label of heretic. The concern of his last days was perhaps centred more on reconciliation with the Catholic Church through the confession and abjuration of his heresy than on commutation of his legal sentence of death. In this regard, Meyer relates another detail: when asked if he had any final words before his death, he turned, as if for permission to speak, to Father André, who counselled him firmly to remain silent.

Among the remarkable black and white photographs in Meyer’s book is one taken of members of the Métis governing council — “l’Exovidat,” in Riel’s language — who were captured after Batoche and were about to recede into the historical silence from which they had emerged. This handful of men, looking out at the camera — some of them subsistence farmers, others hunters of the disappearing buffalo, all looking poor, forlorn, yet defiant — had been given a voice, at least for a while.

Throughout history, the apocalyptic voice is ever the voice of the dispossessed and, with rare exceptions, proves no match for “la Puissance.” This power is manifold, but one of its ever-present elements is surely money. Gabriel Dumont, who escaped after the battle to the U.S., was to experience in dramatic fashion the bitterness of subjection to this elemental force. For several months, he had to make ends meet by acting in Bill Cody’s Wild West, displaying for enthralled paying audiences the marksmanship that had made him a formidable hunter of the buffalo once plentiful in the Canadian North‑West.

Bruce K. Ward is the author of Redeeming the Enlightenment: Christianity and the Liberal Virtues as well as Dostoyevsky’s Critique of the West: The Quest for the Earthly Paradise.