Our earliest memories of learning language can reveal a lot about how we relate to words and meaning. At three, for example, Julie Sedivy was in “the sweet, stinking darkness” of a barn with her new friend, Maura, who was introducing her to farm animals. The linguist-to‑be didn’t understand her companion yet, as she and her family had just arrived in the Dolomites, but she was enthralled by the “bewitching confusion” of what she heard. “I belonged to it,” she writes of her swift attachment to Italian, “and it to me, in a familial way that had nothing to do with reason or with wanting or with deciding.”

Within two years, Sedivy had been exposed to five languages, to varying degrees: Czech, the tongue “of my parents and country of my birth”; German, “spoken by the orderly and temperate Viennese”; Italian, “in which I roamed with the wild Maura”; French, “learned in the back alleys of East Montreal”; and English, which represented “authority and aspiration” and would eventually “dominate all the others.” She credits her family’s peripatetic lifestyle and these early immersions for her enduring interest in words.

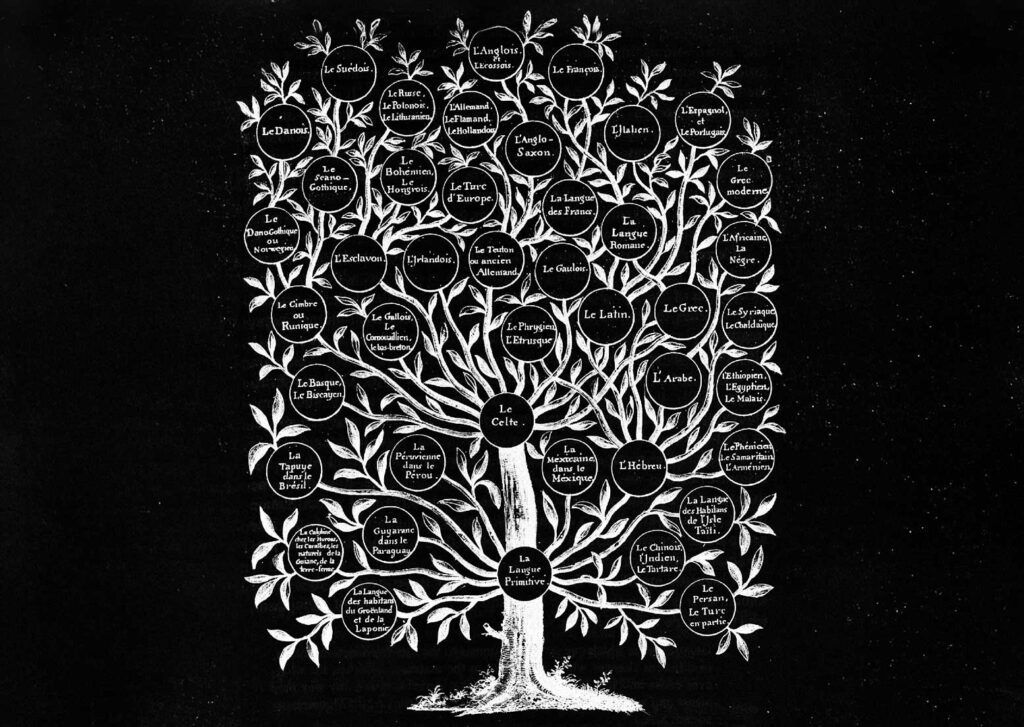

Branches of language as imagined at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Félix Gallet, Arbre généalogique des langues mortes et vivantes; Nicole Bryczkowski

Linguaphile: A Life of Language Love traces Sedivy’s personal and professional preoccupation. The book is presented in three parts: “Childhood,” “Maturity,” and “Loss.” The meandering narrative oscillates between reflections, addresses to family members, and digressions into theory. Throughout, she returns to the singular importance of reading — the “sheer liberation” that allowed her to “vault beyond the grasp” of others and develop a strong sense of self. More than once, I was reminded of a line from Roland Barthes’s A Lover’s Discourse: “To try to write love is to confront the muck of language: that region of hysteria where language is both too much and too little.” This speaks to the great challenge Sedivy sets out for herself. She attempts to articulate her devotion to words and understand their structuring role in her most intimate relationships.

A true reverence for the world’s vernaculars shines on every page. Wide-ranging analogies extend into beautiful prose. “Language was an ocean whose floor plunged straight down from the coastline,” she says of learning English in kindergarten. At a young age, Sedivy noticed how bilingualism allowed people to pluck and arrange phrases into “the most vivid and arresting bouquet.” There is no shortage of symbolism. In her world, you can pledge allegiance to language, disentangle it, slice it into segments, or ride its current. It can cheat, shift, dissolve, and sing. While it may be filled with cracks and fissures, “an exquisite logic runs through language even at its most disheveled.” Her imagery is by and large affecting, though mixed metaphors produce a sense of disjointedness at times.

Sedivy is at her best when probing memories, particularly of times when words failed her, as in the aftermath of her father’s death. “Where his voice should have been,” she writes, “there was a bewildering silence.” As she grieved, Czech — their shared mode of communication —“became very quiet for a long time.” These powerful vignettes complement longer expeditions into linguistic theory.

During some of Sedivy’s critical forays — which range from explanations of scientific studies to cultural analyses — I found myself relating to a woman who dropped out of one of her introductory linguistics classes at the University of Calgary. Sedivy recalls the “self-assured” student thanking her for the lecture — the first of the semester — but explaining that the course was not for her. “You see, I’m a poet,” she said, with no need for a forensic “dissection of language.” Sedivy initially dismissed the idea that “to learn more about language risked snuffing out its spark of the divine.” But ultimately she came to understand and empathize with the student’s perspective (even if she doesn’t agree entirely). “Several decades later, the poet’s fears seem less irrational to me,” Sedivy admits. “The thrill of new discovery has never left me, nor has the sense of a widening of vision. But it is true that, after years of keeping pace with the daily demands of a scientific life, I allowed my attention to literature to slip.”

Like that student, I felt protective of what I didn’t know about language and was eager to maintain some of the mystique. But Sedivy’s open-ended revelations only added to the wonder. She writes of the divide she felt with her mother: “The words I had once shared with you split and drifted like continents moving away from each other, words upon whose meanings we could no longer agree.” In a memorable passage on aging and loss, she chooses to view her increasingly frequent “tip-of-the-tongue experiences” as evidence of a hard-won vocabulary rather than as a sign of diminishing mental faculties. She homes in on moments when the effect of speech evades explanation and reason. More than her expertise, her curiosity makes her an excellent guide through the morass of miscommunication.

Linguaphile is full of labyrinthine detours and offshoots, but it also leads to arrestingly beautiful vistas where readers can reflect on their own relationship to making meaning. Sedivy’s memoir is a reminder that some of the most timeless insights into the human condition are uncertain: suspended between knowledge, memory, and mystery.

Lindsey Harrington was shortlisted for the Fiddlehead Creative Nonfiction Prize in 2023.