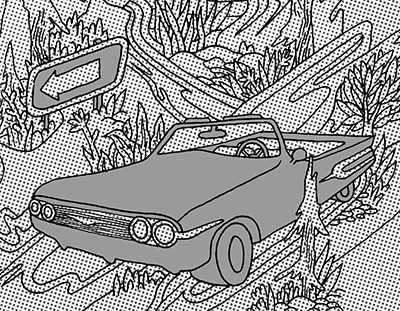

Two young guys with thick hair, dressed like extras in Rebel without a Cause, are roaring down the open road in a 1960 Chevy Impala convertible. Eager to see their Maritime home recede in their rear-view mirror, and with only $26 in their pockets, they are heading directly for the Toronto of 1970. “Lock up your daughters,” they shout defiantly into the winds of Canada—Pete and Joey aim to take the big city by storm.

So begins Don Shebib’s important and now iconic feature film, with comic bravado and high expectation. Pete McGraw (Doug McGrath) and Joey Male (Paul Bradley) are tearing down the highway the way thousands upon thousands of Maritimers had done for at least a decade before them. They are fuelled by optimism and confidence, certain that the Toronto of their dreams will welcome their talent and energy. The region from which they have fled can no longer contain their ambition. They seek nothing more than opportunities for work and play, and the material success that attends to those opportunities. They could not be more wrong.

We already have a sense of this. Pete and Joey are inspired by the example—and dress code—of James Dean. The tight jeans and kick-ass boots, carefully shaped pompadours, shrugged shoulders, the smokin’ vintage convertible: these are the conspicuous signs of a fading if not altogether dated masculine social code. But the Toronto of 1970 to which they are hurtling is partaking of a different and more popular cultural ethos. Fifties fashion and attitudes had given way to a rebellious aesthetic of another kind, to the mainstreaming of flower power, or a post-hippie feminization of masculinity. Middle class men had adopted wide-collared shirts and even wider ties. Consider the decidedly curvy, feminine architecture of the New City Hall at Toronto’s Nathan Phillips Square, built just five years before Pete and Joey headed down the road. In 1970, protest against the Vietnam war was furious. Love Story was the top-grossing film. Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge over Troubled Water” dominated the charts.

How could Pete and Joey, with their raw and unsophisticated Cape Breton ways, fit into such a world? Not gracefully, to be sure. Indeed, Goin’ Down the Road is a brilliant and measured story of precisely this painfully awkward encounter between two naive and well-meaning men from Eastern Canada and the modern urban centre of the country from which they are practically by definition excluded.

Jake Pauls

As is often the case in the history of film, the severely limited feature budget with which Don Shebib had to work actually served the film’s aesthetic well. In large part, the film owes its iconic stature to the uncanny naturalism of its story-telling. Shebib, like so many other Canadian filmmakers, had put in his time at the National Film Board and the CBC and was familiar with producing documentary material. Pete and Joey’s journey plays out against the real cityscape of the time, from the ghastly light of a Salvation Army shelter to the vulgar neon of Yonge Street. We know Pete and Joey are cinematic inventions, but the world in which they roam is unfiltered and unstaged, as familiar to any Canadian as a bottle of beer. Moreover, both McGrath and Bradley perform their roles with such persuasive authenticity that they have thoroughly become their characters.

Such dedicated realism at every level has reinforced the film’s importance in the history of Canadian cinema as well as its enduring appeal. Especially memorable is the extended scene in which Pete follows a beautiful young woman of the supermodel Jean Shrimpton variety up to the classical music section of A&A Records on Yonge, itself an iconic site for locals and tourists alike. In this woman and in the Eric Satie piece to which she listens, Pete glimpses and hears something he wants, something just too far out of reach. The scene is astonishingly expressive in capturing the enormous divide between Pete’s dreams and the growing dead-end reality of his life. Perhaps nowhere more than in this wordless encounter with everything Pete longs for—and cannot have—is his alienation more profoundly realized.

Goin’ Down the Road is a sustained achievement of such poetic realism. It is certainly worthy of its own book-length study and so it is that Geoff Pevere has delivered a comprehensive survey of the film and its sometimes vexed critical reception. As Pevere documents in Donald Shebib’s Goin’ Down the Road, the reaction after the film’s initial commercial release was enthusiastic and generally approving. No one had ever seen anything quite like this before, on an English-Canadian screen at least. Its apparently seamless harnessing of the tropes of documentary realism was startlingly affecting, at once fresh and familiar. Viewers were inclined to see in the comic misadventures of Pete and Joey a relentless optimism against all odds and even reality itself. Pevere cites the early reviews, “gushing” as they were in the important newspapers of the day. Clyde Gilmour, Robert Fulford, Jim Bere and others recognized the possibility that Canadian cinema had finally arrived. Moreover, when the film opened in New York in 1970, celebrated reviewers such as Judith Crist and Pauline Kael were all over it. A young and smart Roger Ebert also saw the film and deemed it worthy, recommending its “unsentimental level-headedness” in the Chicago Sun-Times. Yes, even the Americans loved it.

By 1972, however, critical appreciation of the film in Canada was undermined somewhat by nervous conversations many of us were having about national identity. Margaret Atwood’s Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature encouraged a reading of the film as an example of typically failed or weak and flaccid Canadian male protagonists. This kind of Road-kill approach was picked up by others who argued a lost-cause sensibility as a Canadian inevitability. For a short time, then, the influence of that discussion clouded the earlier celebration of the film and diverted a full and more open appreciation of its achievement. How quaint a lot of that seems now. Pevere’s study of the critical shift is itself fascinating, for it does point to just how vulnerable the cultural community was about national identity issues in the seventies, and how much further it had to go to see Road as a more significant work of film in its own right. As Pevere observes, what was initially viewed as “the one” that marked the beginning of a bona fide national industry became a “contentious Canadian classic.” One can appreciate why director Don Shebib remains pretty contemptuous of the critics and defiantly grumpy about what they all get on about.

That said, it took a while for other reviewers to redress the balance, such as Christina Ramsay who insisted on seeing the film for what it was: “a nakedly honest and piercingly clear reflection of not only what Canada might have been at the time, but how preoccupied it was with becoming something else.” Furthermore, she saw in Pete and Joey the possibility of real heroism, since they had the “balls to show something about living in their country that their country didn’t want to look at.” Now there is a line the famously salty Shebib could get behind, to be sure.

Pete and Joey endure in ways Shebib could hardly have imagined. There is a lot of them in Trailer Park Boys Ricky and Julian, who covet their vintage “shit mobiles” and vigorously defy the middle class. And there is certainly a lot of them in rowdy man Jake Doyle, whose ’68 Pontiac GTO is as much a character on Republic of Doyle as Jake himself. There are easterners who no longer need to go down the road in search of fortune or false dreams. In many ways, Pete and Joey already paved that way.

Noreen Golfman is the provost and vice-president (academic) pro tem at Memorial University of Newfoundland.