Phyllis Lambert is most famous as the founder of Montreal’s Canadian Centre for Architecture and as the fierce protector of Montreal’s built heritage. But as her book Building Seagram makes it clear, of all her achievements she is most proud of having been the driving force behind one of New York’s landmark buildings.

The year she was born—1927—her father, Sam Bronfman, took over the Joseph E. Seagram and Sons, founded in the 19th century. He merged it with his family’s Distillers Corp., grown prosperous by making use of the business opportunities presented by Prohibition in the United States. Some of his associates had been the leading gangsters of the day. He was to build the new firm into the world’s largest distilling company.

Incredible as it may seem, until the age of 27, Phyllis Lambert had minimal contact with her father. When he came home to Montreal on weekend visits from his office in New York after Prohibition was repealed, the owner of Seagram Distillers showed interest only in his boys, whom he considered in the line of business succession. Not that the sons were grateful for his attention—his fierce temper and dominating personality terrified them.

Phyllis, the first born, admits in Building Seagram, her handsomely illustrated book about the company’s New York headquarters, that she was a child “with a strong aversion to all talk about business and money,” a dreamer, a loner, an artist in embryo from the age of nine, whose truest friend and parent-substitute was her sculpture teacher Herbert McRae Miller. “The two afternoons a week I spent in his studio were the most continuous, concentrated time I would spend with anyone as a child or adolescent.” Miller was the only person who ever read to her.

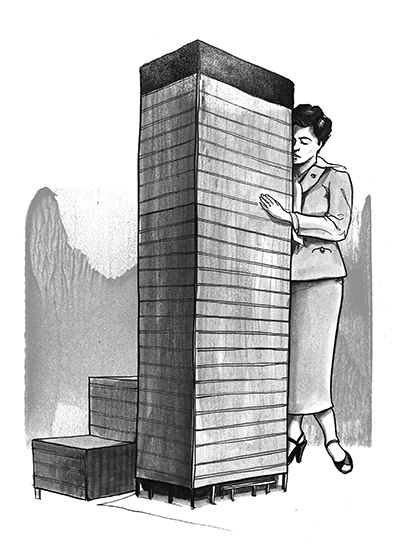

Dave Barnes

Her escape from this chilly milieu came when she was sent to Vassar College, where she studied the history of art and architecture and encountered people deeply interested in the arts. In 1949, a year after graduating, she married a French banker, Jean Lambert, and moved to Paris, but the marriage was short lived.

In 1954, she was working as a sculptor in her Paris studio when SB (as she refers to her father) discovered that he needed his expensively educated daughter after all. The post-war liquor business was booming and Seagram had outgrown its rented quarters in the Chrysler Building; the company planned to build new headquarters on Park Avenue in the showy style SB favoured. In Montreal, he had built a turreted fake Tudor-Gothic castle on Peel Street as the home of Distillers Corporation-Seagrams Limited, decorated inside with Highland daggers, sporrans, tartans, shields and a full suit of armour. He sent his daughter a sketch of the proposed Seagram building in New York, designed by the New York firm of Periera & Luckman, in a style SB called “Renaissance Modernized.” Phyllis was horrified.

She wrote back an impassioned eight-page letter, reproduced in the book, explaining why the proposed building would look vulgar and urging her father to put up a building that was of its time, without reference to any previous era, a building to inspire those who saw it and worked in it, one that would enhance not only the firm but also the city. SB asked her to move to New York to help.

Appointed director of planning, Phyllis Lambert rose to the challenge. She was given the job of finding an architect and after much list making, consultations with experts and travels around the country to look at the work of the leading architects, she settled on the émigré visionary Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, former director of the Bauhaus, then teaching in Chicago, although he was not licensed to build in New York and, at 68, was considered by some to be too old. Mies had designed glass skyscrapers in the 1920s in Germany that could not yet be built. New American building technology was now up to the task. For Mies, architecture was a search for a visual language that could express new realities and permit new ways of living; Lambert fell under his spell and later studied architecture under him in Chicago.

Her father’s associate Lou Crandall, who was in charge of construction, suggested that Philip Johnson, former head of the department of architecture at the Museum of Modern Art, work in association with Mies, and also brought on board a team of other associate architects and engineers.

Several photographs reproduced in the book show Lambert as a slim, serious, dark-haired young woman wearing glasses, the only female in a thicket of middle-aged architects, consultants and financiers. Philip Johnson later said that her presence at meetings meant that nobody tried to cut corners; it was “like having a crown prince” in the room.

Mies believed that New Yorkers were hungry for space, and his proposed design called for an open plaza at the base of the building—radical at the time—that he likened to a clearing in the urban forest.

Lambert describes how the two architects and their associates set up a large office in Manhattan, where they spent their time constructing models. Mies holed up in his cubicle smoking large cigars, drinking coffee and thinking. Among the problems to be solved: how to create a building that does not take up the entire site, how to get half a million square feet of space, where to put the elevator core, how to make the plaza welcoming to people, how many steps were needed from the street to the raised plaza, how to maximize the size of the bays (the distance between the building’s load-bearing inner supports), how to create the bronze curtain wall and how to finish its corners.

The book takes us through the construction process in detail, mainly based on archival and secondary sources, and tells us a great deal about Mies’s history, his training and influences and previous projects that generated the ideas he plowed into the Seagram building, his finest achievement. (Readers who do not know their mullions from their spandrels, or an H-beam from a cross member, may find this heavy going.) A chapter is devoted to the tremendous contribution of Johnson, who designed the interior of the building, the finishes and the hardware, and worked on the luminous ceilings and other indirect lighting schemes, all of which immeasurably enhanced Mies’s bold design.

Anyone who has ever been subjected to an extended home renovation will marvel at the fact that the building took only 18 months to design and another 18 months to build. In the end it cost $36 million instead of the $15 million budgeted. But it astonished people with its severe elegance, noble materials, its use of specially manufactured grey tinted glass that cut down the sun’s heat, its luminous glow at night when the windows seemed to disappear and its attention to detail. Among Johnson’s specifications were venetian blinds that stopped in only three positions so that the building’s exterior rhythm was not marred by the helter-skelter raising and lowering of the window coverings.

(Most of these refinements were abandoned when Toronto’s TD Centre, with its bald and windy plaza, was built a decade later in the same international style. For instance, instead of bronze, the TD Centre used black painted steel mullions.)

A section of Building Seagram is devoted to the creation of the Four Seasons restaurant in the pavilion at the foot of the office tower. Lambert retells the story of the commissioning of the supremely neurotic abstract expressionist Mark Rothko for $35,000 (in current dollars, $2.5 million) to produce a suite of paintings for the Four Seasons. After painting some 30 large canvases Rothko refused to allow his deeply spiritual art to be used as mere décor in an expensive restaurant and backed out of the contract. Lambert writes that she understands his decision but adds nothing to the account of the failed commission given by James Breslin in his 1993 biography of Rothko. (The incident is the subject of the recent Broadway play Red.)

Most of the 38-floor structure was to be rented. But when the Park Avenue building was first discussed with New York’s real estate agents and promoters, they suggested that the city’s elite firms might be disinclined to rent offices from someone with Bronfman’s background. The quality of the building, however, enhanced the image of both Seagram’s products and its owner, a man obsessed with quality and legitimacy. Renting it was not a problem.

After 1958, when the building was completed, Lambert continued to be in charge of the corporate art collection and helped organize art and photography exhibitions on the fourth floor. She encouraged use of the plaza for jazz and dance performances, and for changing installations of sculpture that added to New York’s lively cultural life.

Lambert follows the story of the building for three decades, until 1988, by which time SB and Mies van der Rohe had both died, the building on Park Avenue had been sold to the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America, and the city of New York was granting landmark designation to the office tower as well as to the elegant interior of the Four Seasons restaurant, which incorporated artworks Lambert had commissioned or bought. The enormous difficulties of preserving heritage buildings, which inevitably brings the public interest in conflict with the owner’s private property rights, are amply illustrated.

There are two stories in Building Seagram, one about architecture and another about a strong-willed and remarkable woman, a sensitive artistic swan born into a family of fortune-seeking ducks. The swan’s story is told reluctantly, intermittently and indirectly.

Phyllis the swan seems to be an outsider in the family who rarely speaks to her brother Edgar, president of Seagram after their father’s death in July 1971. She was not consulted about plans to sell the Seagram building in 1980, or about the later shift in the company’s business away from what the Bronfmans know best (liquor) into the slippery field of movies and entertainment.

In 2000, while at the architectural Venice Biennale, Lambert heard from a journalist that the family firm had been sold to Vivendi, a French water utility company. Seagram was no more.

The Seagram Building endures.

Judy Stoffman is an arts journalist based in Vancouver.