In an entry dated “Spring 1880,” Dukesang Wong recorded in his diary, “I have decided to venture to that country they call ‘the Land of the Golden Mountains.’ The next ship that departs for those shores is the one which I shall be on. Because I cannot build upon my own land in this country, it is right that I should attempt to seek land over the ocean.” In a subsequent entry, marked “Late Summer 1880,” he confessed trepidation about his “wild and uncivilized” destination, where “people kill each other daily” and “all the business and the laws are controlled by white people, while we are not permitted to rule over our own actions.” He wondered if there were less “barbaric” areas: “My life doesn’t yet have the signs of impending death, and my family has not yet carried on its name. With no wife and children, my life has still to be lived, and I am curious what this new land will bring.”

These words were written when Wong was in his mid-thirties. For more than a decade — the diary begins with entries from 1867 — he had been preoccupied with his family’s honour and a tragedy that had blighted their name. Then he realized that, according to the straitened rules and regulations of the elite society into which he had been born, opportunities at home were scarce. Instead he pursued a belief that became a theme of many immigrant stories: that opportunities were brighter over the far horizon — in the Golden Mountains of the Pacific Northwest. Wong’s introduction to “this new land” would be Portland, Oregon, but he eventually moved on to British Columbia.

All the while he kept a record of his observations, a chronicle of events and self-reflection, on a journey that led him to work on the Canadian Pacific Railway. It is a tale of terrible hardship and deprivation, compounded by the racism that Chinese workers experienced and the chillingly utilitarian attitude with which this new and barbaric land regarded them.

The Diary of Dukesang Wong is presented as “the only known first-person account by a Chinese worker on the construction of the CPR.” As such, its appearance is a welcome and signal event, one whose origins can be traced back to an undergraduate thesis submitted four decades ago by Wanda Joy Hoe, Wong’s granddaughter. As a sociology student at Simon Fraser, she discovered her grandfather’s diary in an archive and translated portions for her paper. (Hoe went on to have a career with UNESCO.)

Years later, the author and filmmaker David McIlwraith came upon the thesis and realized its importance. With Hoe’s participation, and adding an introduction by Judy Fong Bates, he nurtured it along to publication, providing context and commentary to help fill in the gaps.

Some narrative gaps proved insurmountable. The archive in which Hoe found her grandfather’s writings was located in a Wong Association branch that was later destroyed by fire (other branches still exist throughout North America). All that remains of the diary’s original seven notebooks is those portions that Hoe originally transcribed with the aid of two uncles. We are thus left with the fragments of a life — a comment offered not as a complaint but with regret and also gratitude. Even with these fragments, we catch glimpses of a much broader canvas. We discover insights and intimations of an experience too long ignored by mainstream histories of a transformative period.

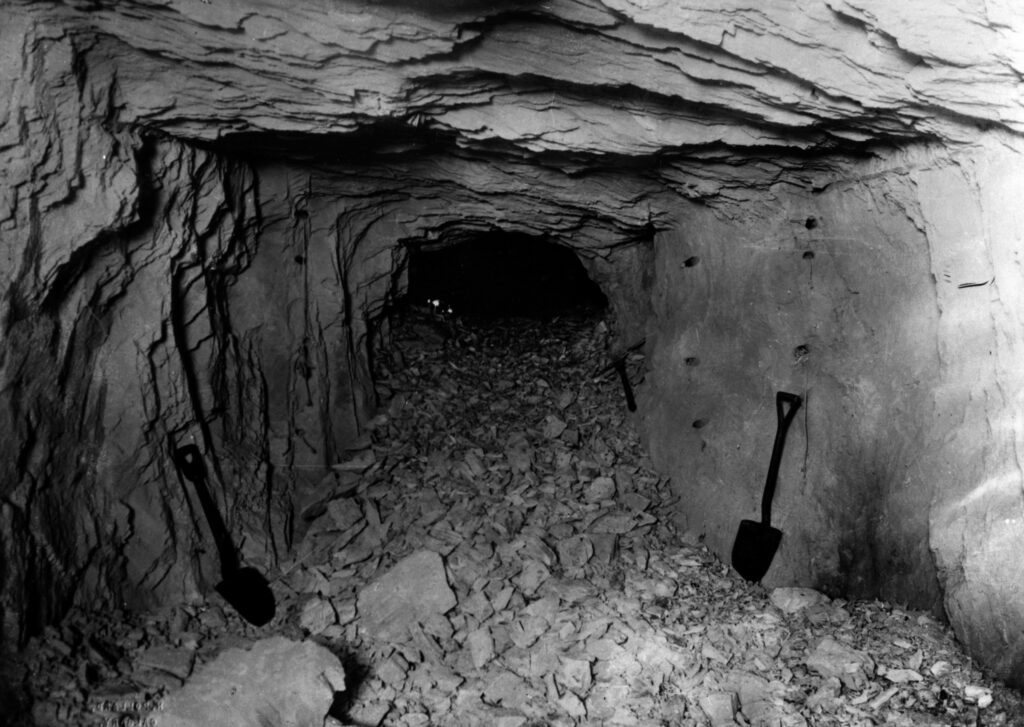

Digging into the archives of a transformative period.

The Province; Vancouver Public Library

The extant diary starts with the upheaval that ultimately led to Dukesang Wong’s decision to emigrate. His father, a magistrate north of Beijing, had weighed in on a land dispute that pitted two families against each other. His position on the matter prompted his shocking murder — at a banquet hosted by the family he favoured. And this crime brought shame on the victim’s family. The trauma of the murder — Wong recalled his father’s agony over several hours, his blackened fingernails indicating arsenic poisoning — was compounded by the social ostracism that derailed his own hope of finding employment within the imperial court.

For years, while earning a living as a tutor instead, he attempted in vain to clear his family name of scandal. At one point, he fell in love with one of his pupils, but he resisted the temptation to act on his feelings, on the grounds of social propriety. “As the tutor grew more and more attracted to his young student,” McIlwraith writes, “his concern and anxiety about the attraction also grew. Like most of the young women of the period in China, Sai Ling had been betrothed in an arranged marriage.” This is a diary that reveals a thoughtful man, whose occasional doubt and dismay were nonetheless superseded by strong self-discipline and a sense of duty.

Eventually, in 1879, Wong committed himself to a “little bride” named Lin, an infant thirty-five years his junior, following a tradition common to the patriarchal structure of imperial China. And that promise — of a wife and progeny to carry on the family name, bringing it honour and distinction — nudged his thinking toward a new life on distant shores. “Lin has been promised to me as my second wife,” Wong wrote. “Ironic that I do not have a first, unless those brief moments with Su‑Lin were first.” He offered no further explanation, though Hoe told McIlwraith “that he was known to have had a first marriage, or cohabitation, in China, and that the relationship produced a son.” (Neither the first wife nor her son followed Wong to Canada.)

With his mandarin background and education, Wong came into contact with Christian missionaries in China, likely Jesuits. He enjoyed multiple discussions with one in particular: “The Englishman cannot have any classical knowledge whatsoever, but he does seem to be well versed in his philosophy.” Later, Wong corrected himself: the man was, in fact, from France, “but in any case, also a barbaric land.” While aspects of Christianity baffled Wong —“It is an interesting concept: my soul to be saved — but from what?”— he relished these conversations, even as he kept reminding himself to hold fast to Confucian principles. He saw Christian teachings as “just another point of view toward this life in which we all must exist, and it is certain, I think, that these lessons are about a good life of giving and helping other people.” When Wong sailed to North America in 1880, he did so aboard a missionary ship.

In Canada, Wong emerged as a spokesman for, and teacher to, his fellow countrymen. It disheartened him to learn that great social upheavals in his native China had sparked anti-Western xenophobia. This enmity was juxtaposed with the realities of anti-Chinese sentiments in North America, including low wages and a head tax. Even the Japanese were treated better, he complained. (However, as McIlwraith points out, had Wong not died in 1931, at the age of eighty-six, he might have witnessed the shameful internment of Japanese Canadians during the Second World War.)

In an entry dated “Summer 1886,” Wong remarked how the “fresh new land” he had long pondered “is a land already full of sadness. The people are beginning to pursue a search for gold. They say it glitters everywhere, and men die for it. It is a peculiar set of values, strange to my humble limited experience, where men fight one another for it.”

What is remarkable about the man who emerges in these entries is the equipoise he somehow managed to maintain even in the face of privation and the tumult of his surroundings. For all his doubts, he displayed a steadiness born of fidelity to philosophical principles, to the “order of life,” and to restoring honour to the house of his father, a restoration possible only when he finally married Lin and started a family.

“It is hard, this labouring,” Wong wrote of his time on the railroad, “but my body seems to be strong enough. The people working with me are good, strong men. There are many of us working here, but the laying of the railroad progresses very slowly. It seems we move two stones a day! And they want this railway built across these high mountains, some two thousand miles!” Later, he decided to become a tailor and set up a business in New Westminster: “There is not enough ready-made clothing from China, and there are no tailors to cut the cloth in our manner. I will be able to earn some money, enough to bring Lin over to this land.” She arrived, with her guardians in tow, toward the end of the 1880s. They married several years later, she a young teenager and he nearly fifty.

If one can praise Dukesang Wong for his dedication to what he considered his duty, one can certainly praise Lin for her equally hard-won adherence to it. Disease, a miscarriage — these were some of the early challenges that confronted her in British Columbia. But the couple had seven sons together and, finally, a girl, whom Wong declared “a great joy for all this house” in the diary’s final entry, dated 1918: “She has come in my old age, a joyous sign, and she will be able to bring me pride, I know! It is good. Her brothers are men now, so she will be assured a good life. She will look after Lin when I leave these lands for the final journey homeward.” The baby girl, whose anglicized name was Elsie, was the future mother of Wanda Joy Hoe. She lived until 1992 and was buried in Vancouver’s Mountain View Cemetery, sharing a tombstone with her mother.

Hoe concluded her transcription of her grandfather’s diary on an upbeat passage, which is perhaps understandable. But in an entry from 1901, Wong once again lamented the strife occurring in his homeland and his sense of alienation in Canada: “I have ceased to desire to return to my village, for I am now of this house, but I am also greatly saddened, for now I can only hope to be buried in a nameless land.” One likes to imagine that somewhere in the diary’s missing pages, he looked back on his life, gazing at his children and knowing he helped give them a name, in this “nameless land,” that they can be proud of.

John Lownsbrough is a journalist in Toronto and the author of The Best Place to Be: Expo 67 and Its Time.