In January 2012, the world’s leading economists, executives, academics, and politicians gathered in snowy Davos to discuss the future of global commerce. With most countries still reeling from the 2008 financial crisis and with populist, anti-capitalist movements like Occupy Wall Street gaining traction, that year’s meeting of the best and brightest was different. “Capitalism, in its current form, no longer fits the world around us,” proclaimed the forum’s chair, Klaus Schwab. It was a declaration that surprised many, as those gathered were typically well served by existing economic and political systems. But crises force people to stare at their own shortcomings and resolve to do better. Davos 2012 was a turning point, at least rhetorically.

Discussions about a greener, more inclusive, and stakeholder-focused mode of capitalism are now commonplace, even in the most affluent circles. Businesses and institutional investors take an increased interest in environmental, social, and governance issues. Renewable power has emerged as a leader in energy investments, with sustainably managed assets totalling over $30 trillion (U.S.). And a consensus has formed that income inequality poses both political and economic risks for nations and industries alike. Yet for all this self-reflection, global emissions have continued to trend upwards, wealth concentrates in a smaller set of hands, and populist dissatisfaction rears its head around the world.

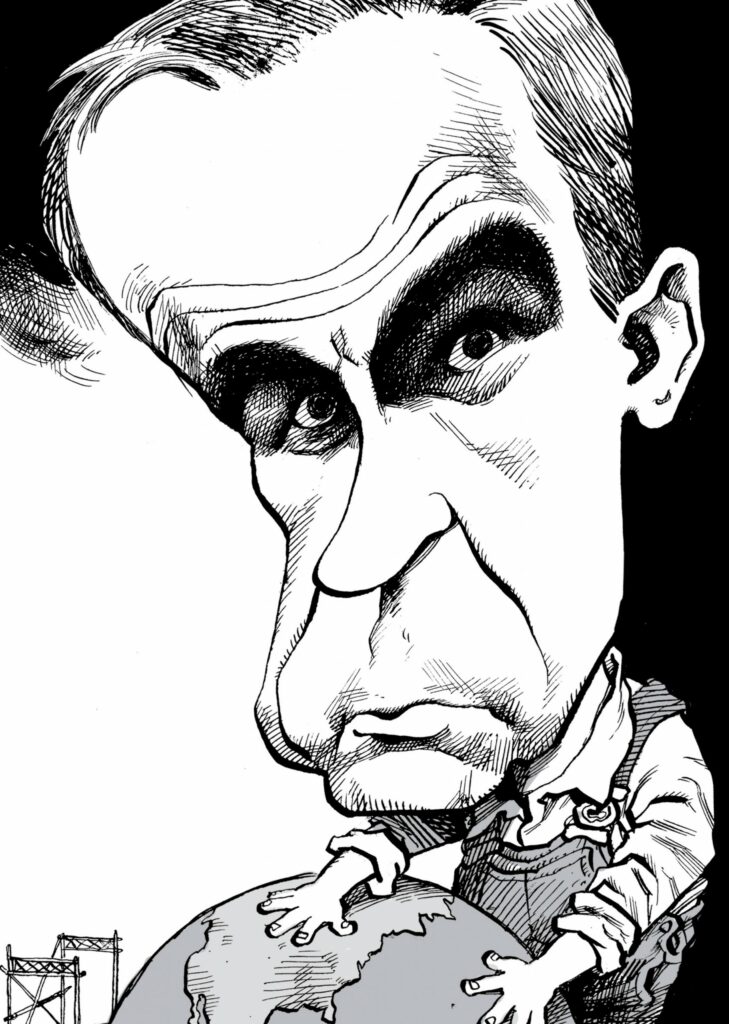

The scaffolding for a better future.

David Parkins

If capitalism is the engine of productivity, why has it fallen short when trying to produce fairer, more resilient societies? There are few public figures better prepared to answer such a question than Mark Carney. As a Goldman Sachs alumnus, the former governor of both the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England, and a United Nations special envoy for climate action and finance, Carney has had a front-row seat to witness the immense power of financial markets and the most catastrophic failures of market-driven economies. With Value(s), he aims to place his personal stamp on the last decade of commentary and to build the foundation for the next decade of action, as international leaders prepare for the post-COVID world, the climate crisis worsens, and the Fourth Industrial Revolution — with increased automation, interconnectivity, and artificial intelligence — rips through workplaces and communities.

While Carney does not dismiss the efforts of his peers in finance, industry, and government, he attributes their shortcomings to systemic misalignment between market value and human values. It’s a sobering analysis, backed by personal observations as well as by centuries of history, philosophy, and political and economic theory. Despite its sombre warnings, Value(s) is in many ways an aspirational book motivated by the potential of markets and technological progress to improve lives, if channelled correctly. “In the coming years,” Carney writes, “we will determine how well the world commercialises fundamental breakthroughs in areas such as renewable energy, biotech, fintech and artificial intelligence. We will decide whether they serve the many or the few.”

Carney’s perspective is reinforced with a sprawling account of how value has historically been defined, from objective origins to a current state of subjectivism. Louis XV ’s physician and adviser, François Quesnay, for example, established the first formal theory of value, which was predominantly driven by the availability of land for agriculture. The Industrial Revolution then saw the emergence of markets and thinkers like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and David Ricardo, who defined goods not only by physical inputs but by labour, technology, and the process of exchange. Neoclassicist economists overhauled this equation. For them, labour did not give value, but it was valued because of the subjective price of what it created.

If value is in the eye of the beholder, driven exclusively by its price, what does this mean for unpriced goods? Or vocations that we rely on for our well-being but that provide limited marginal contributions? To Carney, we have transitioned from a market economy to a market society, highlighted by structural failures laid bare in the global financial crisis, the pandemic, and the looming climate disaster.

Carney began his tenure as the governor of the Bank of Canada during the 2008 crisis, and he saw first-hand both inadequate regulation and the erosion of values that historically underpinned finance, such as fairness, integrity, prudence, and responsibility. Financial institutions prioritized growth, innovation, and opacity at the expense of transparency and risk management. Good ideas in moderation were abused in excess. Eventually the wheels came off. The crisis irreversibly hurt families, businesses, and workers across the country, but it also provided resounding clarity on the limitations of financial markets: “Just as there are no atheists in foxholes, there are no libertarians in financial crises.”

COVID-19 has brought another lesson in the undervaluation of resilience and the lack of attention to risk mitigation, showing that most governments had not focused adequately on health care capacity, biopharmaceutical production, or protections for vulnerable workers. But the pandemic has also revealed what people value: “We have acted as Rawlsians and communitarians not libertarians or utilitarians. Cost-benefit analyses, steeped in calculations of the Value of Statistical Lives, have mercifully been overruled, as the values of economic dynamism and efficiency have been joined by those of solidarity, fairness, responsibility and compassion.” When tested, nations have overwhelmingly favoured common goals over individual gains.

While touting the successes of leading businesses and governments, however, Carney understates the exceptions to this rule: all those businesses that failed to protect their front-line staff, those governments that have continued to resist livable wages for personal support workers, those corporations that have abused wage subsidies while enriching shareholders. His underlying argument — that we will see continued attention paid to systemic risks and expert-informed decision making — is a fair one. But it would be a mistake to assume this perspective is shared universally.

Carney examines climate change both with optimism, about the lessons learned from prior crises, and with realism that governments and businesses are on pace to drive the planet further into its sixth mass extinction. Yet we can’t rally behind ambitious goals without consistent metrics, so he devotes considerable attention to necessary disclosure standards that would bring accountability to sustainability reporting. The financial sector introduced the generally accepted accounting principles after the 1929 Wall Street crash, and it improved disclosure requirements after the 2008 meltdown. We will not get a second chance to correct course after this next crisis.

To that end, Carney seeks to build alignment around a common set of values to guide future activities and to insulate societies from crises on the horizon. Citing dynamism, resilience, sustainability, fairness, responsibility, solidarity, and humility, Carney launches into a manifesto on “how Canada can build value for all.” He points to a productivity agenda that invests in workers — rather than in specific jobs — and ties employment insurance supplements to retraining programs, particularly for the digital economy. He emphasizes the ongoing shift to an “intangible economy” and advocates for an improved intellectual property framework. And he calls for better bridging between academic research and commercialization, while asking governments to update labour legislation to reflect changing workplaces, with particular attention to poorly defined roles and responsibilities for “dependent contractors.”

Value(s) is at its most vital when it details the dual crisis and opportunity for Canada to transition to green energy. “Prime Minister Stephen Harper was partly right,” Carney argues. “Canada could be an energy superpower. Blessed with diverse energy sources including hydro, oil, natural gas, uranium, solar, wind, tidal and biomass, we have become the world’s fifth largest energy producer.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, Carney’s specific recommendations, like a predictable carbon price path and increases to fuel efficiency standards, find considerable alignment with the policies of the Trudeau Liberals. That said, he is far more candid than the Liberal leadership about the heavy lifting required to reach net zero. “When I mentioned the prospect of stranded assets in a speech in 2015, it was met with howls of outrage from the industry,” he recalls before pointing to the finite lifespan of oil and gas as well as the inevitable decline of various forms of commercial agriculture.

As governor of the Bank of England, Carney developed a mixed reputation for drifting outside his mandate. As an author, he no longer contends with those guardrails. The policies and principles that he puts forward in Value(s) are hardly radical, but they are nonetheless ambitious in a country that rarely does ambition well.

Readers who have followed Carney’s career will naturally be curious about where all this thinking is headed, as he does not write or act like somebody who simply wants a footnote to his biography. Carney is one of the most active Canadian voices on climate change, finance, and public policy. He is working as Boris Johnson’s finance adviser for the upcoming UN climate summit in Glasgow; he is the vice-chair and head of ESG and impact fund investing for Brookfield Asset Management; and he regularly appears on television to uncomfortably dodge questions about his political aspirations.

For some, his informal entry into the political arena raises red flags. Ken Boessenkool, an economist who held senior roles in the offices of British Columbia premier Christy Clark and Prime Minister Harper, referred to Carney’s speaking role at a recent Liberal policy conference as “the beginning of a journey that will end in deep regret and the erosion [of] a critical independent pillar of a modern economy — the central bank.” The Conservative Party of Canada was less tactful, responding to his appearance with a press release that congratulated him on “trendy new economic experiments that are popular with Davos billionaires.” In other words, people are paying attention.

Value(s) will have political reverberations, but it reads nothing like a typical candidate memoir. Unlike Justin Trudeau, who hinted at his first campaign with a carefully concocted set of vignettes that reinforced his brand, Carney makes no attempt to narrate his own political ascension. His deep dive into economics, philosophy, and monetary policy will test the patience of some readers, and even his personal commentary tends to be self-deprecating. He dismisses his Bank of England appointment, for instance, as a “total accident of history.”

Yet, at the same time, Value(s) offers a clear and confident presentation of Carney’s place in a broader social and historical context, as well as the transformative change that he is uniquely qualified to advance. Just as Richard Nixon, an ardent anti-Communist with a reputation for muscular foreign policy, was the only politician the public trusted to normalize U.S. relations with China, Carney, an Oxford-educated economist who spent his highest-profile professional years perched on top of the world’s second-largest gold reserve, enjoys unique credibility to champion fairness in the markets.

And so he is arguably at his best when taking on finance directly: “Once I became Governor of the Bank of Canada in early 2008, I would receive delegations of investors in ABCP or bankers that were exposed to the mess. Their requests had the benefit of being consistent — consistently self-interested.” It doesn’t take central banking experience to be disgruntled with “too big to fail” talking points, but there are few authors or professionals able to address the problem with such clarity and precision.

Ultimately, despite his coherent and passionate advocacy for progressive causes, Carney is hard to place politically. Skeptics of Value(s), or of Carney more personally, question whether capitalism, a system that intrinsically rewards short-term financial returns, is capable of achieving such lofty long-term outcomes. After all, it’s one thing to prioritize altruistic ESG initiatives and improve financial returns. It’s another to prioritize these initiatives at the expense of the bottom line. And while Carney points to several memorable case studies and a meta-analysis from the Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment that found mostly positive relationships between sustainability reporting and financial results, the success of this movement has been far from linear.

Consider Carney’s example of Danone, with its “One Planet. One Health” commitment to nurturing healthier and more sustainable eating habits. After championing a new legal structure that would embed the company’s corporate mission in its bylaws, Danone’s chief executive, Emmanuel Faber, proclaimed last June that the multinational had “toppled the statue of Milton Friedman.” Danone’s board felt less bullish this year and removed Faber from his position the same week that Value(s) was published.

Nobody said the shift toward stakeholder capitalism would be easy, but the question isn’t whether private enterprise should play a leading role in bringing positive change. It’s whether we can afford the alternative. For Carney, the answer to this question is never in doubt:

I am not a market fundamentalist in that I do not reflexively think that the market is the answer to everything. At the same time, I have seen the market’s immense power in multiple situations, and I know that the market is a critical part of the solutions to many of humanity’s greatest challenges. We won’t achieve the Sustainable Development Goals without growth; and we won’t get to net zero without innovation, investment, purpose and profit. My experience has made me a profound believer in the market’s ability to solve problems. I have seen day in and day out the very human desire to grow and progress, of people’s yearning to make better lives for themselves and their families.

Continued growth isn’t a fairy tale; it’s a necessity.

True to this philosophy, Carney outlines a range of measures to enable businesses to prioritize integrity, responsibility, and purpose: from commitments to board diversity and longer-term executive compensation structures that include non-financial metrics to the advancement of training programs that strengthen employee engagement.

Capturing the “disciplined pluralism” of capitalism, while reforming it to explicitly serve human interests, is a messy process that requires shared commitments from governments, industry leaders, and, most importantly, the general public. Appealing to broad coalitions, Carney is optimistic about the potential for societies to usher in change after years of foot-dragging: “Social movements can move slowly and then with surprising speed.” It’s a hopeful perspective grounded in an understanding that governments and businesses are dependent on the moving targets of consent and trust. And it will serve Carney well if his name ever appears on a ballot.

For evidence that nations and industries will always learn lessons reactively and belatedly, cynical readers can easily point to the takeaways that were ignored following the SARS outbreak or to the warning signs of global warming that have been consistently overlooked. And they may be right. However, the depth, urgency, and timeliness of Value(s) might just inspire leaders in all walks of life who seek to escape this cycle. It provides clear analysis on the impacts of unchecked marketization and a vision for the global leadership role that Canadian governments and businesses can play.

As Klaus Schwab and many others have put forward, capitalism needs to evolve to survive. But as the past decade of incremental change has shown, this evolution does not just happen. It requires compelling insight, strong leadership, and broad public support. In Value(s), Carney demonstrates two of three. The next steps will be largely up to us.

Jeff Costen worked for three cabinet ministers in Ontario’s most recent Liberal government. He is now a principal at Navigator Limited.