Many times in the months since March 2020, the politicians, pundits, and boosters have assured us that the pandemic presents us, if we squint hard enough, with a golden opportunity. The mounting misery offers the chance to build back better — whatever that means. Usually, the “building back better” crowd flesh out their slogan by itemizing rousingly ambitious projects that have long filled the dreams of policy wonks: investments in housing, education, infrastructure, and renewable energy, along with the creation of new jobs in the green economy. These are, to be sure, worthy and wonderful initiatives. Yet the fact that nearly all of these ideas long predate the arrival of COVID‑19, however world-historical this moment may be, is somewhat deflating: we’ve heard it all before.

Will any truly new, previously unthought ideas arise from our current upheaval? It’s still too soon to tell. Nevertheless, we assure ourselves that something original and previously unthinkable must come. That’s what history unfailingly offers up, conventional wisdom holds: rupture, crisis, transformation. This far into the plague years, we have ready-made narratives to buttress our expectation that the coronavirus will somehow radically change everything. Our relentless drive to historicize the present means we’re already seeing this moment as akin to the great flu pandemic of 1918, from which the Roaring Twenties sprang. And how can we gainsay anyone who reaches for this analogy? It’s a story of jubilant reinvigoration after death, one we perhaps need these days, when the promise of a decisive, vaccine-driven triumph over our viral adversary has begun to fade with each new variant.

Stretch the analogy too far, though, and dangers arise. For instance, this type of thinking blinds us to the potential of failure that pervaded the public imagination more than a century ago. To those suffering through the flu years, the ’20s boom was a faint possibility amid other, more dire ones; it was not the inevitability that it seems to our twenty-first-century eyes. And, of course, the 2020s are not the 1920s. The Prohibition-style speakeasy at which I can get liquor now smacks of hipster nostalgia; Zoom and FaceTime alleviate the loneliness of social isolation. More darkly, no vaccines existed for the flu. We could extend the list of contrasts endlessly. Our understandable desire to imagine our present through the prism of the past poses the risk of flattening out vital differences through analogy, which truly works well only when used in concert with its opposite: disanalogy.

Oh, and one more small difference between then and now: in the 1920s, the prospect of social and economic revival wasn’t widely understood to be inextricably entangled with environmental collapse. Our current era’s awareness of unchecked climate change and the loss of biodiversity renders our visions of a post-plague world entirely different from those of the flu years. A return to normal isn’t good enough. Not only did our ecologically devastating pre-COVID normality give us rising sea levels and charred forests, it encouraged the perilous human-animal interactions of the global wildlife trade that, so experts suspect, may have enabled the virus itself. What’s more, it gave us the carbon-spewing transportation networks that supercharged its spread.

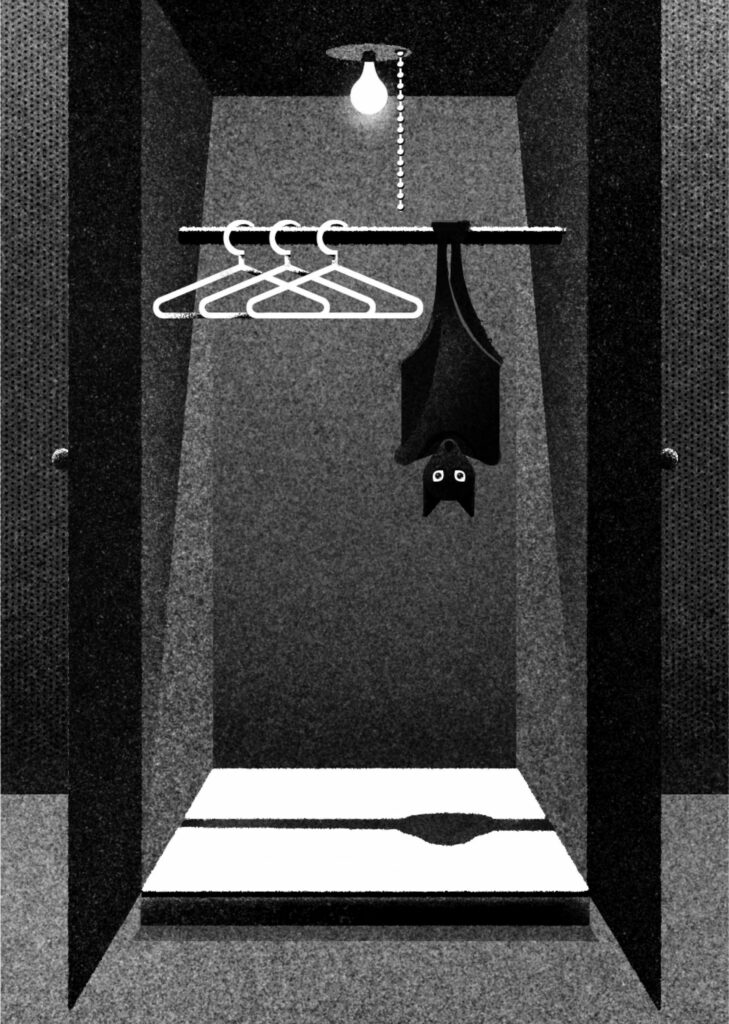

Confronting the skeletons in our closet.

Karsten Petrat

That viral and ecological calamities are so entangled exposes another pitfall of imagining a pandemic recovery through silver-lining narratives. Such approaches narrow the aperture of our consciousness to a predicament-beset present. In this way, they risk cutting other, longer-term forces out of the picture. So much of what we experience as crisis has a long gestation period. Often our tragedies arise from entrenched, deep-seated political and social arrangements not easily amenable to the quick fixes that crisis management demands.

Slowly, we are coming to understand the true roots of what we once naively called natural disasters: the escalating floods, droughts, and forest fires that are hallmarks of our time. These aren’t, of course, wholly natural. In many cases they are demonstrably human disasters, symptoms of planetary change caused largely by ways of life in the global North.

These sweeping changes have come about as part of the Great Acceleration. Environmental historians point to the plunge in planetary health after roughly 1945, as measured by exponential increases in ocean acidification, carbon emissions, biodiversity loss, and other key indicators of ecological collapse. Our experience of the Great Acceleration arguably involves another sort of acceleration: namely, of the frenetic media coverage through which it is conveyed to ordinary Canadians. Open your newsfeed nowadays and you’ll likely be bombarded with doom-laden coverage that comes buttressed with ample environmental data. It’s enough to jolt us into political action — or, just as likely, to make us feel like giving up entirely. After all, staving off catastrophe will require revolutionary change, not exactly a known specialty of our governments. Institutional inertia, politicking, and kowtowing to the usual established interests seem likely to scuttle the wide-ranging transformations that climate scientists say we need. Even building back better, we increasingly sense, won’t be enough.

Early in the pandemic, we were awash in photos of city streets empty of their usual denizens, quarantined at home, while the wilder urban residents took a look around. In those viral moments, J. B. MacKinnon sees glimmers of hope, of alternative ways of living that we rarely if ever ponder. The pandemic showed us that we miss some things “much more than we knew. Everyone enjoyed the clear blue skies and the fresher air in our lungs; we all seemed to thrill at every sign of a natural world reborn.” MacKinnon’s superb The Day the World Stops Shopping poses the thought experiment its title describes: What kind of world might be born if we all drastically reduced our shopping, spending, and overall consumption?

Environmental recovery, however partial, is one obvious answer. But how MacKinnon visualizes this recovery coming about is startlingly unobvious and illuminating. Sure, most of us are now dimly aware that our shopping harms the planet. But MacKinnon’s thought experiment involves a halt not just in buying things but in consumption more generally. This allows him to introduce little-discussed but potentially transformative ways of perceiving the commodities we buy. Take the concept of a circular economy. Still unfamiliar to most, this term refers to an economic system that minimizes waste in diverse ways, such as by designing products for maximum durability and, when those products grow old, recycling them as the raw materials for new stuff. One especially eye-opening chapter exposes the enormous waste that is created by our constant pursuit of clothing, along with increasingly influential efforts by fashion pioneers to reimagine their industry in circular ways, despite innumerable barriers.

One crucial way of fostering a truly circular economy for our clothing, one that minimizes its resource consumption, is to stop acquiring so much of it in the first place. This point encapsulates a broader theme of MacKinnon’s book: the need to make do with less. After all, another obvious result of MacKinnon’s scenario of a steep drop in shopping would be global economic depression. Grappling with this fact is what ultimately makes MacKinnon’s work so stimulating. As quickly becomes clear, curbing consumption is not merely an environmentalist act. It’s also an opportunity to scrutinize the foundations of our social, political, and economic systems, as well as the forms of being they encourage. Why is our political discourse inseparably wedded to unending economic growth? Why is consumption an index of self-worth for so many of us? Around which other systems of value might we organize our lives if we kicked our addiction to consumption?

Our conventional measurements of well-being arguably distort as much as they reveal. The best-known metric, the gross domestic product, is strangely crude and often registers palpably baleful phenomena, including soaring inequality and environmental devastation, as positives. Over the last decade, many countries, including New Zealand and Iceland, have begun de-emphasizing GDP in their budgeting and policy making. Rival metrics such as the genuine progress indicator, which tallies the social and environmental costs of growth, enjoy increasing clout. These alternatives offer more than new lenses for reckoning with the gains and losses of what we call the economy. Rather, they remind us that “the economy” is itself a construct, a tool for conceptualizing and quantifying a dense web of transactions across society. It’s also all too easy to forget that before the 1940s, the concept as we understand it today simply did not exist. MacKinnon unsettles standards of value that, for most of us, are so ingrained as to be nearly instinctive; he prods us to imagine them anew. This is his book’s most ambitious and impressive feat.

MacKinnon does not view the end of growth that shopping’s demise would induce as an unmitigated calamity. With brief, spryly written chapters, he takes us to destinations as far-flung as Finland, Japan, Ecuador, Germany, and Namibia in order to chart the hidden opportunities afforded by slowing consumption. Although these chapters form a broad narrative arc, they can also easily be enjoyed piecemeal, as article-sized stand-alone units. Each brims with startling facts and engaging interviews. Not every reader will emerge a convert to MacKinnon’s perspective, but almost all will have some of their deepest values shaken.

How might we plot an actual political path to achieving the more ecologically attuned world that MacKinnon envisions? The environmental journalist Arno Kopecky offers some answers, as well as other questions, in The Environmentalist’s Dilemma. The eponymous dilemma with which he grapples is one that consistently hamstrings climate change activism: Our awareness of onrushing ecological catastrophe sits alongside a countervailing sense of unprecedented well-being. The planet is suffering, but, on the whole, a lot of everyday folks are doing pretty well. Yes, ice sheets are melting, but aren’t the advances in human rights and reductions in global poverty and technological innovations of recent decades proof that ours is an age of progress? Environmental destruction has accelerated the rise of new infectious diseases, but isn’t it miraculous that we can now develop vaccines so quickly? Kopecky calls this new normal “a constant background jangle that corrodes public discourse and poisons our politics.”

Living amid the tension between remarkable flourishing (at least for many in the global North) and impending doom poses unique challenges to productive thinking. One of the major ones is to deliberately, scrupulously remember prior worlds. “Each generation grows accustomed to a diminished ecosystem and fails to register that anything might be missing,” Kopecky writes. “In this way, we never realize that we’re catching fewer and smaller fish than our parents, or that there’s nowhere near as many bugs as before.” Our ability to adapt to new environmental conditions blunts our awareness of large-scale change. For Kopecky, stoking society-wide reflection on how much the world has lost is the crucial step toward the radical politics that he views as necessary to renewal.

Attending to remembrance, however, runs up against other psychic challenges. Among the greatest is the damage wrought by a media landscape awash in anger-fuelled commentary, rampant disinformation, and mounting polarization. The vitriol doesn’t just suffocate sober thought or drive us to distraction. It leaves us unable to agree on even the basic facts of the planet’s health. Like MacKinnon, Kopecky is interested in an environmental politics that encompasses fundamental questions of how we discuss and understand our social, political, and economic lives.

But Kopecky approaches the challenges in a more unreservedly activist spirit than MacKinnon. Though MacKinnon’s personal misgivings about consumption are never in doubt, his measured, neutral tone suits his essays’ characteristics as thought experiments conducted through profiles of little-known intellectuals and initiatives. Kopecky, by contrast, dives headlong into some of the most publicized debates and protests of our times, from the election of Donald Trump and the pipeline politics of Jason Kenney to protest movements such as Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion. Many of the strongest chapters in The Environmentalist’s Dilemma — most notably “Rebel, Rebel,” which is a searching exploration of the dynamics of protest movements — ask how ordinary people can be persuaded to vote for stridently environmentalist policies in an era of material abundance. Do dramatic, disruptive protest actions galvanize or alienate ordinary people? Which forms of politics become viable as increasing numbers of people dimly grasp their complicity in ecological collapse? How does a focus on personal environmental responsibility — reduce, reuse, recycle — shroud the fact that without broader systemic change, urgent goals will never be achieved?

The expansiveness of the dilemma that frames these essays — the world is dying yet human life seems by many metrics to be better than ever — allows Kopecky to write with unfailing verve on a vast array of topics. (Beyond his explicitly political themes, he reflects on the ethics of travelling to Disneyland and the curious paucity of novels about the climate crisis.) Occasionally the looseness of Kopecky’s frame leads the book to terrain only obliquely related to environmentalism, and while he decries media-fuelled polarization, he sometimes draws upon it by invoking common tropes of the culture wars. Given his environmentalist focus, for instance, it’s surprising that he elaborates the oft-repeated and certainly defensible argument that Trump is a fascist while barely discussing the former president’s actual environmental policies.

Nevertheless, these essays are consistently stimulating and often moving, sometimes deeply so. The chapter “Once upon a Time in Deutschland,” in which Kopecky’s German heritage sparks a stirring reflection on notions of responsibility and complicity, is a particular highlight. In the author’s hands, the book’s titular dilemma emerges in all its richness, ambiguity, and tension as a foundational opportunity and challenge for contemporary environmentalism.

If Kopecky’s and MacKinnon’s calls for radical change go unheeded, perhaps because of sheer hopelessness, we’ll resign ourselves to eventual annihilation. This expectation inspires Len Gasparini’s thirteenth poetry collection, Götterdämmerung. The volume’s back cover labels its title poem “an ecopoetic cri de coeur,” but this portrayal undersells its playfulness. Granted, the poem, which sits at the collection’s heart, sees the extinction of the human species as nature’s hope for rejuvenation: “Will everlasting peace come to the earth / when we humans no longer inhabit it?” And the answer seems unequivocal: “Let fire purify / the whole anthropogenic mess.”

Faint hope flickers nonetheless. Gasparini’s many allusions to T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, which is also fixated on the prospect of regeneration, make that clear enough. (Whitman and a host of lesser-known nature poets likewise echo in Gasparini’s lines.) And even as the poem laments that “nobody dances anymore,” it offers a tentative, provisional path for renewal:

Love’s ever spiraling ouroboros

moves the cosmos. The life of the cosmos

resides in rhythm. The cosmos dances.

Playing a one-nighter at Mudbugs Saloon,

Jerry Lee Lewis said: “If you don’t dance,

you don’t know what happens.”

What might it mean to dance? Gasparini plays coy and invites us to reimagine our relations with a despoiled nature that’s seemingly beyond repair. In this way, “Götterdämmerung” joins a recent body of environmental poetry — see work by Juliana Spahr and Jorie Graham, among others — that recognizes the irremediably damaged state of our environment and eschews grand visions of an unblemished nature beyond civilization’s reach. It tests the powers of a nature poetry that has abandoned hope for ecological restoration.

The poem’s kaleidoscopic structure reflects the disorder and disharmony it depicts. An Eliotic shoring of fragments against ruins — rather than any kind of wholesale renewal of the earth — seems all that is possible amid the destruction. What’s left for us is solace and consolation, not unalloyed hope. The faint chance of a new life for the earth hovers in the penultimate stanza: “(Scatter my ashes on the lone prairie / where the coyotes howl and the wind blows free).” But even this hope hinges on a death, the self’s transformation into dust.

Canadian letters boasts a long line of inventive poets of the environment — P. K. Page, Don McKay, Daphne Marlatt, and Jan Zwicky, among many others — and Götterdämmerung is an accomplished addition to this lineage. Rather than some outright apocalyptic annihilation of humanity, Gasparini yearns for new relations between it and the earth. This becomes especially clear with the book’s closing essay, “The Third Poetry.” In it, Gasparini honours the work of the mid-twentieth-century Mississippi nature writer Walter Anderson, who “believed that what wastes the beauty of nature is the deflected eye of human subjectivity.” In other words, our penchant for anthropocentrism leads to poetry that subordinates the natural world to the artist’s mind and deploys aspects of it merely “as metaphors, as vehicles for our own concerns.”

But the best poems can transfigure nature, not instrumentalize it. Gasparini claims and seeks to demonstrate that “the only basis for a mutual understanding can be found in the very substance of poetry: metaphor, which is a bridge from the minor truth of the seen to the major truth of the unseen.” Gasparini quests after the paradoxical. Working within the strictures of language, a vehicle of human selfhood, he strives for states of being beyond that selfhood entirely.

Gasparini also argues that humans “and the other species of the earth have a relationship in need of serious therapy” in what he calls “this Anthropocene epoch of high technology.” With the term “Anthropocene,” Gasparini invokes an increasingly popular moniker for our age: the proposed name for a geological era in which the fossil record will surely reflect the predominance of human activity in shaping planetary history. Gasparini’s recourse to the language of geology and species captures a crucial tension of our moment, one with which all these books wrestle, whether directly or indirectly. However anthropogenic climate change winds up inscribing itself in the fossil record, it arguably won’t reflect the actions of humans as a species. Rather, it’s a specific subset of that species — largely, the inhabitants of the global North — whose activities are already forming the disquieting geological age. That is to say, the term “Anthropocene” papers over global inequalities in laying blame for destruction on Homo sapiens. It allows us to forget that many of us will suffer — indeed are already suffering — for the actions of others.

Yet the geological tone of “Anthropocene” usefully awakens us to the vast spans of time within which our present behaviour resonates. This is the term’s contradiction: it both illuminates and obscures. Its doubleness captures the challenges to human thought posed by calamities such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and a world of more frequent floods, droughts, and fires. Comprehending our planet’s woes requires keeping one eye on our immediate world and its glaring inequities, and another on the repercussions of our actions across millions of years.

Each in his own way, J. B. MacKinnon, Arno Kopecky, and Len Gasparini advance our quest for this elusive mode of thought, this actual opportunity for foundational change, which is without a doubt the signal task of our time and beyond.

Spencer Morrison is a professor of American literature at the University of Tel Aviv.