The assumption with elegy is that the composite of remembrances and anecdotes comes together to form a single, unmistakable portrait of the deceased. Yet any attempt at a faithful rendering of the comedian Norm Macdonald, who died in September, aged sixty-one, leaves little more than a jumbled sketch. The man was publicly unknowable. Fiercely anti-confessionary, his jokes were constructed so that they yielded a splintered image of his private life, with each shard refracted paradoxically through another. “In any art, the key is concealing,” he told Esquire back in 2016. “It’s not revealing.”

When art and artist become inseparable, it’s usually because audiences care more about the creator than about the work. Some writers and performers have turned this shift in interest into opportunity, eagerly leading us on tours of their private lives and, especially, their struggles. Such exhibitionism has no bearing on quality, though, and serves only to distort the measure of what it means for an artist to be generous. Indeed, it threatens to change the value of art from how it makes us feel to how clearly we perceive the figure behind it.

The pseudo-biographical outpourings of Tolstoy, W. G. Sebald, Bob Dylan, David Bowie, and J. M. Coetzee, to name a few, have turned revelation into a game. Their works teeter on the edge of the real, threatening (or promising) to unload some juicy details but never straying far from the fiction and falsehoods that pepper their stories — thereby ensuring the sanctity of the process. Such “autre-biography,” with its intentional twists and dead ends, can feel unsatisfactory, if not downright condescending. Macdonald’s work belongs here, where the poetics of self takes precedence over the person.

The comedian George Burns once quipped, “I don’t tell jokes, I tell anecdotes and lies.” That’s presumably what Macdonald meant when he called stand‑up “false by nature”— a koan he seemed to have subsumed into his own life. A common ploy of his act was to begin a personal story, then spin it out with intimate details before ending on an archaic one-liner, as if to say, “You didn’t think any of that was true, did you?” He wasn’t there to tell you about himself; he was there to tell jokes. The truth didn’t matter, because you were laughing. Macdonald’s foray into literature was no different. His 2016 memoir, Based on a True Story, was a circuitous modern-day Tristram Shandy; a straightforward biography would have been a betrayal of everything he put into his craft.

The key was concealing.

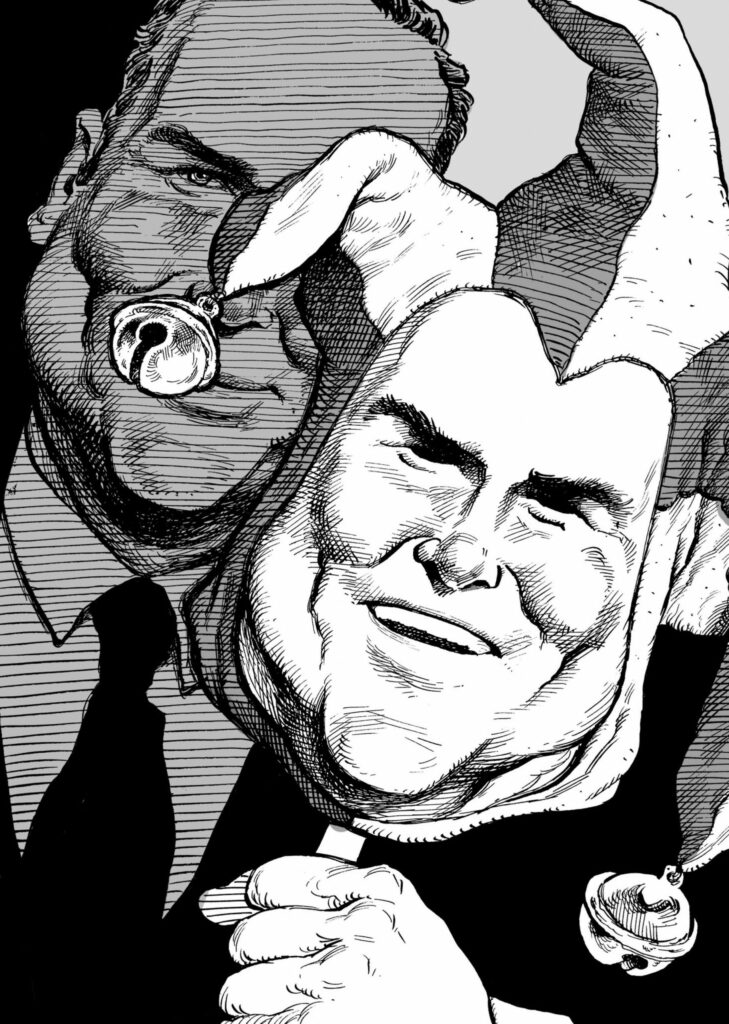

David Parkins

Born in Quebec City in 1959, Macdonald performed in comedy clubs across North America, eventually landing in Los Angeles, where he flopped on Star Search and briefly wrote for sitcoms such as Roseanne. His ascent toward fame began in 1993 when he joined the cast of Saturday Night Live. He eventually became host of “Weekend Update,” SNL’s facetious take on the news. With his anchorman looks and the marked timbre of his voice (a voice as distinctive as Burton Cummings’s or Peter Gzowski’s), it seemed a role he was born to play. That his time on the show coincided with O. J. Simpson’s trial and the subsequent rise of twenty-four-hour cable news only gave him more to work with. His jokes, which were brave and blunt and often did little more than point out an obvious truth, were a balm against the up-to-the-minute, minutiae-obsessed cycle of coverage. Macdonald understood that sometimes what you needed to know was right in front of you, and that a funny thing required no manipulation. Like a scab, a joke was better when left alone.

Macdonald wasn’t afraid to be too subtle either. His loyalty was split between the joke and the audience, but, when pressed, he sided with the joke. He admired brevity and believed the ideal bit was one where the setup and the punchline were identical. Such a thing might sound easy, but it was the comedic equivalent of a six-word short story. What’s more, Macdonald’s desire to please didn’t stem from the cloying desperation that bogs down so much of live comedy. He would let his jokes hang, particularly the ones that bombed, and refused to plead for laughs. This is what he loved about performing: the risks that lay in a mistimed joke, the possibility of falling out of the good graces of the crowd. It was this attitude that made him the last dangerous cast member of SNL and the last one not afraid to be fired, which, of course, he ultimately was.

To listen to Macdonald was to hear a man wholly at ease with himself, delighting in the pleasure of thinking on his feet. He tried to impress no one, intent only on telling his joke, all the while taking care to conceal his hard work — what he called the “artlessness of art.” One of his methods was to play his considered insincerity off others’ sincerity, beguiling them with a bait and switch that left people guessing not what Macdonald had said but what he had made them say. That style didn’t play well when scripted, as several failed star-vehicle TV shows proved. He later branched out into podcasting, a much better fit, where he interviewed his friends and heroes, within comedy and without: Roseanne Barr, Jack Carter, Jane Fonda, the country musician Billy Joe Shaver.

Macdonald’s career most closely mirrored that of Shaver, among all his guests. Both had an influence that went far beyond their public standing, popularity, or recognition. Both were beloved by insiders of their craft. Neither achieved staggering fame, but neither did they flame out. They are remembered in their respective realms of comedy and music as purists, idealists. And even if this trait ultimately cost them their chances at the kind of notoriety that allows for a comfortable retirement, they were too devoted to their art to change who they were — in each case, unpredictable and subversive.

Who expos’d to others Eyes,

Into his own Heart ne’r pry’s,

Death to him’s a Strange surprise.

Whether Macdonald was aware of this parallel will remain appropriately, characteristically, and pleasingly unknown.

J. R. Patterson was born on a farm in Manitoba. His writing appears widely, including in The Atlantic and National Geographic.