A major difference between “serious” and “soothing” literature, as Northrop Frye proposed in his conclusion to Literary History of Canada, from 1965, is that one challenges the existing order while the other reaffirms it. Serious works prod the reader toward “making the steep and lonely climb into the imaginative world.” Soothing books, on the other hand, encourage one “to remain within his habitual social responses.”

Paradoxically, there are few genres more soothing than the thriller. Although these suspenseful, plot-driven narratives are designed to get hearts pounding, palms sweating, and pages turning, they don’t push readers into a lonely imaginative world. Rather, they make readers hyper-aware of their own physicality as well as their place within the established order.

Canadians seem to have an appetite for this reassurance. A 2021 study by BookNet Canada showed thrillers to be the second most purchased genre, after fantasy, accounting for 14 percent of all fiction sales in the country, or some 1.8 million units. (This figure is down from that of the previous year, when thrillers secured the top spot with 27 percent of sales.) Given this success, any pragmatic publisher would salivate at the prospect of hawking one of these popular tales written by the most popular sort of person: a celebrity.

Last fall, three such blockbusters landed at bookstores: State of Terror, a collaboration between the mystery writer Louise Penny and the former United States secretary of state Hillary Clinton; Denial, a high-stakes legal drama by Beverley McLachlin, who served as the seventeenth chief justice of Canada; and The Apollo Murders, the retired astronaut Chris Hadfield’s lunar adventure, which takes place in an alternative past during the Space Race. All three were bestsellers, of course, so count on more celebrity thrillers arriving this year and beyond. In fact, south of the border, one already has: Dolly Parton recently released Run, Rose, Run, a partnership with the novelist James Patterson, about — what else — a singer-songwriter in Nashville.

Chasing after yet another celebrity-authored bestseller.

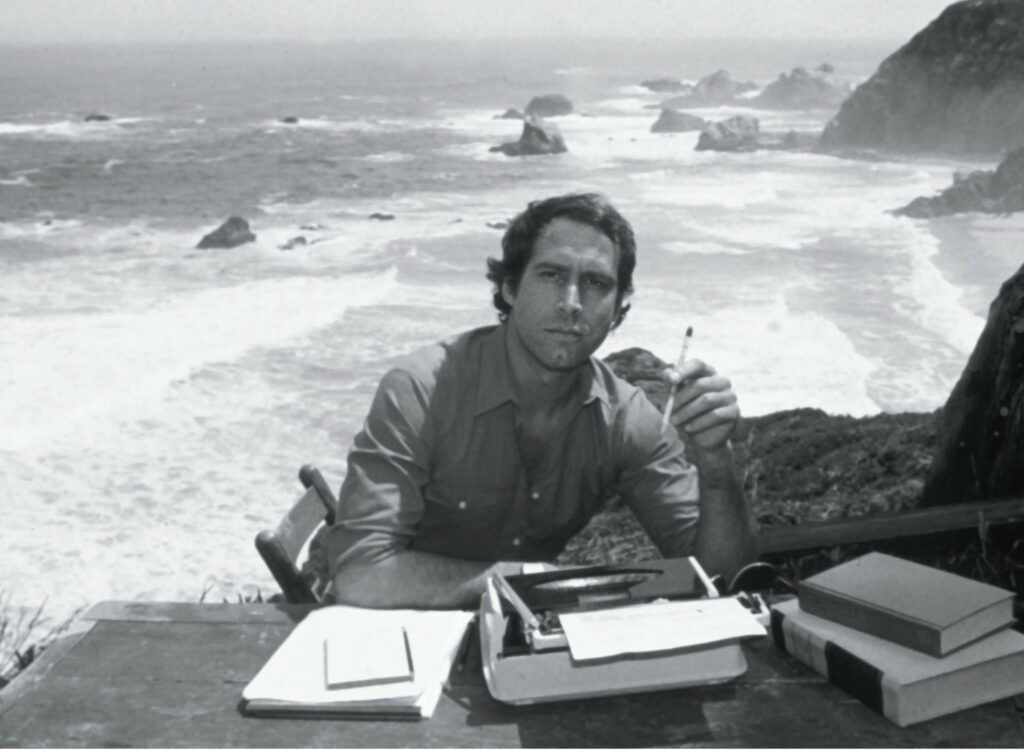

Seems Like Old Times, 1980; Photo 12; Alamy

Without fail, these titles fictionalize their authors’ decidedly non-literary careers. Presumably, the point is to capitalize on their status in order to cross-sell in an unrelated market. Disney fan? Buy some Mickey Mouse–shaped waffles. Metallica fan? Buy a T-shirt. Clinton, McLachlin, or Hadfield fan? Buy their books. You’d be hard pressed to find a better example of what the Marxist philosophers Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer called “candy-floss entertainment”: art that reflects the surface of social reality but embodies, at bottom, “the culture industry,” in which works become “just business.” The novel itself isn’t the point; the “absolute master,” the meaningful content of the creation, is the industry itself. Among the sweetest candy floss on offer, celebrity thrillers validate another existing order: the production of standardized entertainment for financial ends.

The novels’ premises reflect that standardization, which is to say they are serviceable, if predictable. In State of Terror, the newly minted secretary of state Ellen Adams tries to stop the detonation of three nuclear devices hidden across the United States. Denial follows the defence lawyer Jilly Truitt as she takes on the “absolute loser” case of Vera Quentin, a woman accused of the mercy killing of her mother, who had advanced bladder cancer. In The Apollo Murders, Kazimieras “Kaz” Zemeckis must lead his crew on NASA’s top-secret mission to the moon, Apollo 18, while staying one step ahead of his Russian rivals.

Each book hits the expected notes. There are betrayals to be explained; clues to be deciphered; bullets to be dodged. Tempers flare; rockets launch; and buildings inevitably explode. Even a few mysterious strangers appear along the way. This reliance on formulas can generate a winking form of enjoyment, as when Hadfield’s astronauts atop the Saturn V exchange knowing glances during the countdown to launch, in a nod to the film Apollo 13. Or when the prosecutors and defence lawyers in Denial ’s courtroom take turns shooting questions at the poor saps on the witness stand. But these tropes also mean that readers see major events coming long before they happen. It’s as if the action is generated by plugging in a series of variables, thereby short-circuiting any promised thrills. The only social responses such predictability will inspire are eye rolling, watch checking, and, during especially cringeworthy passages, wincing.

The quality of the text varies. McLachlin, who writes from the lawyer Jilly’s first-person perspective, does a fine job. She is at her best when she is drawing imagery, such as a dress that hangs off the emaciated defendant, Vera, “like tenting,” or a fiery trial speech that colours “the victim in strokes of virtue.” Hadfield’s attempts are less successful. Let’s just say that the first two lines of his novel —“Flat. Flat, as far as the eye could see”— turn out to be unintended metafictional commentary. His prose has the personality of a saltine. Clinton and Penny’s sentences are even worse; they have none of the flair one might expect from the originator of the line “basket of deplorables” or from the creator of Chief Inspector Armand Gamache. Take the initial description of State of Terror ’s protagonist:

In her late fifties, Ellen Adams was medium height, trim, elegant. A good dress sense and Spanx concealed her love of eclairs. Her makeup was subtle, bringing out her intelligent blue eyes while not trying to hide her age. She had no need to pretend to be younger than she was, but neither did she want to appear older.

While the book features a few engaging scenes, such as the tense countdown before a crowded bus blows up in Frankfurt and a feisty confrontation between Ellen and the Russian president, Maxim Ivanov (very obviously a Putin stand-in), such moments are tempered by example after example of astoundingly mediocre prose. At one point, when a group of American troops exit a helicopter, they “literally hit the ground running.” Charles Boynton is introduced as Ellen’s chief of staff not once but twice in the first four pages. Clinton and Penny seem to anticipate an audience stricken with either ennui or short attention spans (or both). Deplorable indeed.

Like State of Terror, the other two books feature some compelling plot points, including Jilly’s romantic reunion with an old flame, Mike, in Denial and the strangely moving “death” of the Soviet robotic rover, Lunokhod, in The Apollo Murders. Although the sales figures seem to indicate that these works are monumental literary achievements — State of Terror alone sold more than 61,000 copies in its opening week and was the top-ranking title in the BookNet Canada survey — each novel is, at best, a decent distraction. Clearly, the people want their candy floss — and they’ll fork over some $30 apiece to get it.

Beyond the famous name on the front cover, which is always presented in large type, the appeal of this type of publication lies in its very predictability. All soothing literature affirms and comforts; it is read, in Frye’s words, for “the quieting of the mind.” The celebrity thriller’s brand of comfort is unique, though, for its unification of elements from two opposing movements in the history of Canadian literature: sentimentalism and realism.

Like sentimental narratives, which follow the exploits of strong (and possibly silent) heroes, modest heroines, and evil villains, celebrity thrillers move quickly and are, for the most part, morally unambiguous. Like realist novels, these stories address contemporary political and social issues: State of Terror deals with nuclear weapons; Denial with euthanasia; The Apollo Murders with space travel (although Hadfield’s book is set in the 1970s, U.S.-Russia relations have become extremely pertinent again). In offering a veneer of seriousness beneath which hides a gooey centre, these titles provide the illusion of weight but no real substance. They create only a superficial picture of our complex present while actually catering to the existing order.

The books’ architecture demonstrates this layered relationship. Their protracted lengths — the three novels range from just under 400 to over 500 pages — belie brief chapters that average a mere six, seven, or eleven pages. Meanwhile, the easily identifiable plot and character trajectories transmute the “serious” subject matter into digestible comforts designed to warm the soul, not probe the intellect. Everything will be all right, they imply; the complex problems of today are reduced to an age-old equation that is easily solvable within the framework of our established values. As the poet Archibald Lampman might have said, they “go rattling like an empty nut.”

In the face of this analysis, it’s easy to take refuge in cynicism. But there’s no need to. It’s true that the literary output of prominent figures is first and foremost a profitable venture. It’s also true that what is produced is not profound — or even necessarily very good — art. But that doesn’t mean the authors aren’t well intentioned. Nor does the public’s appetite for these stories signify anything gross or sinister. Sometimes a little relief is welcome, if only to remind us of what we’re leaving behind when we make those steep and lonely imaginative climbs.

In a world that is often hostile and complicated, these titles generate plain and simple pleasure. When the very term “CanLit” is under fire for excluding a lot of what Canadians like to read, we would do well to pay more attention to the cultural cachet of popular works — warts and all.

Alexander Sallas can now collect his frequent flyer miles as Dr. Sallas.