Collections are made of intentional exclusions and inclusions, but sometimes books are stolen, lost, or slotted onto shelves at random without licence or record. The whole is defined both by what it contains and by what falls outside of it — or down the stairs after a piano lesson.

One night last winter, on our way to my children’s music class, I thought I’d be clever by dropping into the Lillian H. Smith Branch of the Toronto Public Library to pick up some holds. Later, the books I’d borrowed went flying onto the sidewalk as I lumbered down the stairs of the piano studio with our wagon. I scooped them up, tossed them in with the children, and hustled everyone home, only to realize when we’d fed the kids and put them to bed — and I was ready to have a sit and a drink and a meal of my own — that one of the loans was missing. Tired and hungry, I headed back out into the night to retrace my steps and scour the dark and empty streets for a paperback that didn’t appear. Sometimes books escape the collection.

The buzz of chance encounters or the pleasure of deliberate collecting?

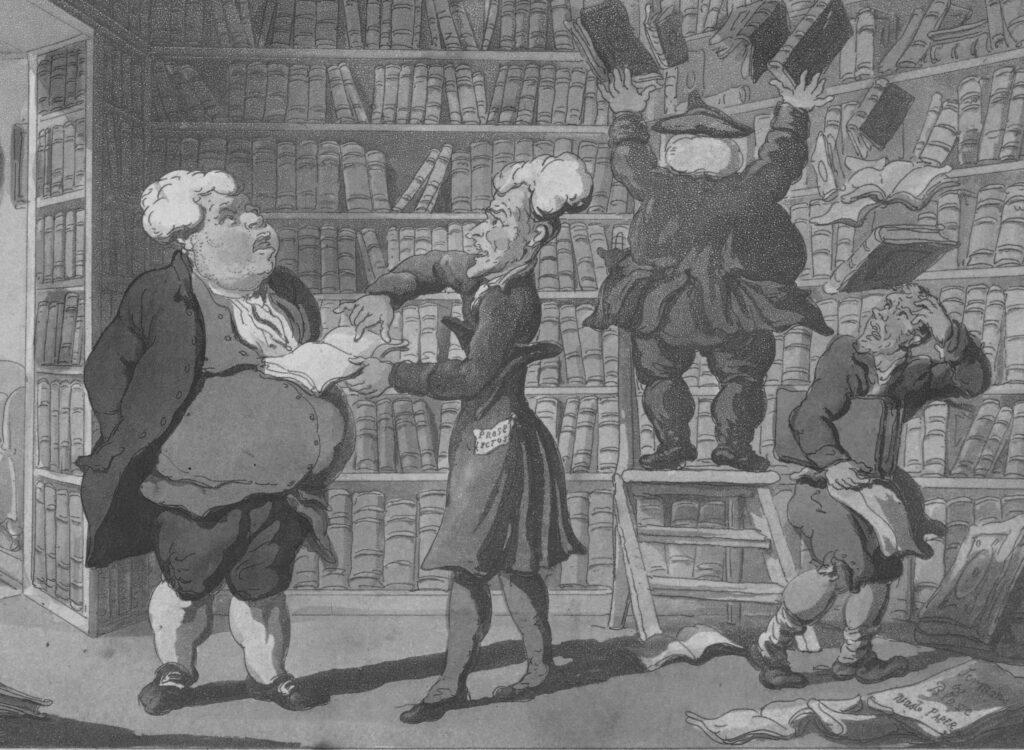

Thomas Rowlandson, 1815; Minneapolis Institute of Art; Minnich Collection

“A bookseller is not quite as surprised as he ought to be by the way objects move through the world,” Marius Kociejowski writes in A Factotum in the Book Trade, a pleasantly digressive memoir about his career selling second-hand books. “The history of the book trade is one of remarkable discoveries.” Kociejowski, a poet, essayist, and Canadian by birth, has worked mostly in England, but I recognize the world he describes from my time at Berry & Peterson, a used bookshop in Kingston, Ontario. Little stores like this, Kociejowski argues, demonstrate “how the character of a city is measurable through its smaller enterprises.” Like cities or forests themselves, independents with their uncatalogued collections are more random and wild than the controlled garden of the library.

With its chatty plethora of references, A Factotum in the Book Trade displays the prose style of someone who takes inordinate delight in the unlikely conjunctions afforded by such places. Kociejowski pinpoints the joys of bookstores for readers and booksellers both, while sketching a miscellany of the personalities he has encountered throughout his career in London. In one story, Leonard Cohen, unrecognized, is thrown out of a shop for asking to see works on astrology. In another, Allen Ginsberg nearly buys a volume of Kociejowski’s own poetry, thinking he is a major Polish writer, and then, realizing and reflecting for a minute, puts it back. Kociejowski often dwells on strategies for buying, selling, and coveting books. As he writes, citing one colleague in the trade, “Booksellers are individuals who solve problems caused by books.”

To borrow Gertrude Stein’s line on words, I like the feeling of books doing as they want to do, and they never seem happier to me than when they are gathered in the more or less orderly jumble of a used bookstore. Kociejowski’s avowal that “there is nothing else that can replicate the thrill of going into an unknown bookshop for the first time” reflects my own sentiments. “I want dirt,” he explains. “I want chaos; I want, above all, mystery. I want to be able to step into a place and have the sense that there I’ll find a book, as yet unknown to me, which to some degree will change my life.” Of one shop in Notting Hill, he writes, “It was always there that I’d find the book I didn’t know I wanted.” In my experience, that is the only and best book you’ll ever find in a used bookstore.

You never know what you’re going to get, but it’s all peering out at you from boxes and under piles in an enchantment of juxtapositions: all life’s variety squished onto the head of a pin and happening at once. Libraries are never the same — except for the returns shelf, perhaps. To me these collections reveal the sedimentary snail trails left by the thoughts of thousands, each volume a record in the bedrock of whims, connections, voices, and ideas that overlap in time. All of it adds up to an archeology of thrills and sentiments that puts mystery itself on display.

It’s hard to describe the frenzy I sometimes feel on stepping into a used bookstore. Entering means balancing the buzz of chance encounters with the deliberate pleasure of collecting. The feeling is amplified if time is tight. Fifteen minutes left on the meter before we absolutely have to go — but let’s just pop in. Inevitably the time is spent rushing about before leaving with an armload of titles that I don’t know if I’ll ever have time to read but that I absolutely have to have — though I had never thought of them fifteen minutes before now. No matter if you never read the books, says Kociejowski, so long as you do read.

Besides the surprise of conjunction, what you’re really shopping for — as I’ve learned by working in bookstores new and used and by watching others and myself browse their shelves — is time. What we can’t quite bring ourselves to put down is the chance to imagine dwelling with any or all of these books for as long as it would take to read each and every word of each and every one. A kind of immortality abides in the idea that we might have all the time in the world to make our way through each and every pile. It’s this feeling we covet and can buy in used bookstores, even more than particular titles. I can still see one of my co-workers raising an eyebrow and shaking her head slowly when asked if we had a certain volume, without first checking to be sure. If a customer wanted it by name, we never had it. Only fools would think they could find something so specific in a shop that just sold time itself.

With A Factotum in the Book Trade, Kociejowski memorializes what could be an ending world. “Bookshops are magic places,” he writes. “And with every shop that closes so, too, goes still more of the serendipity which feeds the human spirit.”

Maybe readers are prone to nostalgia — the feeling that books are always already disappearing — because it’s easy to feel we’ve lost so much time while reading. Shops are indeed closing, and habits are changing as much as streetscapes. Nostalgia always begs the question of whether the object of its mourning matters. Maybe too much importance is placed on spaces that are being swallowed by new technologies. Surely, we would still browse if all the bookshops closed — and maybe that’s mostly all we do now online anyway, always browsing even more than choosing, because you never have to leave the internet to go home.

Being able to look things up online puts into question whether and why we might need a physical book, and the internet has certainly dissipated some of the hunger for ownership. As Kociejowski mentions, online searching has drained the antiquarian trade of profit. Collections have always been the product of chance over time, but building them is no longer about the thrill of the physical chase. Dealers will tell you that prices used to be higher before the internet allowed buyers to compare copies and costs. You had to nab a sought-after edition whenever you happened to see it, so the total included a premium for chance itself.

“Scarcity and value have never intrigued me as much as the improbable directions things go,” Kociejowski writes, remarking on the unlikely trajectory that landed a James Joyce collection in Tulsa, Oklahoma. “Where would we be,” he asks, “without the wonderful journeys books make through the world?”

I’ve never been more surprised by how objects migrate than the time I went to get the soles of my boots mended at a tiny below-grade shop in Chinatown and behind me in line was a woman hoping to repair the same flaw in her set of the same boots. We even wore the same size. The footwear had drawn us through Toronto to this precise spot, shelved us in line together through the logic of the chance encounter, the Dewey Decimal System of happenstance, as though the boots themselves were in charge. We overlapped in one particular square inch of the city by simultaneously wearing the same shoes to the same point of disrepair and bringing them to the same little place at the same time. Clearly, it seemed in that moment, we are not all so different: just extra copies of the same book, sometimes a different edition or imprint, here and there a few variegated traces of reading left on our spines, some copies with a few more trips through the checkout system, but everything more or less in common.

Convinced that having already walked in each other’s shoes meant we might already be friends, we went for coffee, only to find we had nothing to talk about but boots. We were as mismatched as a reader and a book paired at random.

The great thing about reading is that you can pick strangers to talk to and befriend. Faced with so many options, though, how do we choose? Why do we pluck some titles off the shelf and not others? Sometimes people toss books out of the collection for fun, just to see where they land. I’ve had this happen.

Not long ago, when I’d thought I was long past having things happen to me in bookstores, a well-dressed stranger bought me a book at Berry & Peterson, where, twenty years before, I’d completed a final credit for my high school diploma by organizing four cases of literary biography. “This is a great book,” an elegant lady in red said to my old boss, as I stood behind her, waiting to pay for my pile.

“Wonderful,” he agreed.

“Do you know it?” she asked, turning to me. “I’ve given it to everyone I know.”

She insisted on giving me the copy when I said I’d never heard of it, despite my protests that I was headed to a cottage and had a lot of reading to do already. “Just leave it there,” she said, clearly delighted at the idea of her favourite book finding yet more strangers by being planted somewhere new.

The world is divided into two groups: those who read every book they’re given, and the rest, those destined to infuriate the others. I have often fallen into the latter category, but I don’t want to say always, because a person can change — so I read the book.

Published in 1977, A Time of Gifts is the first volume of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s trilogy about his time trekking through Europe in 1933. It’s a glowing and nostalgic view of a series of landscapes and communities about to be destroyed by the Second World War. I’d never heard of Fermor before the lady in red handed me his book, and I opted not to google him until I’d read most of it.

“Not many Americans go for Fermor,” Kociejowski writes, because, he suggests, there “may be just a bit too much Harris Tweed in his style.” Reading those words made me feel very American. In fact, Kociejowski references Fermor several times. He’s one of the many voices whose once intense popularity has faded, whose names were known and then forgotten, leaving their works sitting quietly in the corner, physical relics of their literary fame, waiting to be picked up again by chance in a bookshop — or a cottage.

I wondered about the lady in red through my whole blind date with Fermor’s book. I wanted to know what it meant to her and why, which worlds it opened for her — so vivid that she’d given away a small library’s worth of copies. Fermor’s placid voyage never caught my interest. Even his mother is happy for him when he announces he is giving everything up to march across Europe, walking though he’s wealthy enough that he doesn’t need to, assuming his readers will find his class tourism romantic. Everyone Fermor meets gives him gifts and offers him places to sleep. Everyone is wonderful, despite the occasional Nazi he encounters: most people, he implies, were not like that. This rose-tinted narrative tries to move past the war by seeing the common good and humanity in everyone, as though memory itself had no complexity or peril.

I think many readers find the sort of travel diarist’s cataloguing of real-world characters that Fermor undertakes less appealing now, maybe because a single person’s perspective on others seems less credible when many of those others are broadcasting themselves daily on social media. Everyone being online all the time diminishes the rarity of the unique characterization. Or maybe it’s because of reality TV, which has transformed the idea of real-time life into something a camera crew can catch better than a writer. For whatever reason, it’s easier today to roll one’s eyes about twentieth-century travel and adventure writers delivering their experiences and encounters as though all the individuals they introduce can’t speak for themselves.

Maybe I wasn’t taken by this book for the same reason bookstores themselves are struggling: the revelation of the rare character or book is obviated by the huge tide of perspectives online. “You want voices?” the internet says. “I got them. Next?”

But I did like that one of the gifts Fermor receives on his journey is a book, because it opened a window onto the stranger who’d given me his and the lesson she’d taken from it. The book I held contained the answer I’d thought I could find only by discovering the lady’s identity. What she’d drawn from A Time of Gifts was clear from what she’d done with it: she mobilized its message of giving to strangers by giving them the book itself. The gift marked one little chance encounter in a bookstore as a way station on a longer journey, the books themselves just moored in port a little while before sailing on their way. She’d chosen one in particular and unleashed it, to make the point she’d drawn from its own pages.

I appreciated the circularity of how her gesture repeated and extended her reading experience into the physical world. Maybe I’m telling this story to thank her and to push the gift one more time around the spiral, by placing the book into your hands. Here: Consider Patrick Leigh Fermor’s A Time of Gifts. Read it — or not.

The lady in red tried to apologize for the fuss and commotion of giving away a book as she bought it. “Not at all,” my old boss said, as we all stood around intrigued, unaccustomed to milling about and chatting, like books pulled off the shelf of eighteen months of pandemic. “This will be memorable.”

So much of reading is, in fact, social. Often it’s a conversation we have with ourselves, through the text an author created for someone to overhear, but we all need to have questions for the books we read. The lady in the bookstore had no idea whether I would like the Fermor, but I knew when she offered it to me that I wouldn’t love it in the way she hoped. I knew from my bookselling days. You can’t just give someone a book to read and tell them it’s good. They won’t buy it.

Bookselling, the craft, involves talking to a person enough to learn what their gut craves — just a little but enough — and knowing your stock well enough to pick something quickly that satisfies the call. You don’t want to talk so long that you become a social outlet. The goal is just to find a book the customer wants to talk to by reading, so that when they’re done, they’ll come back for help buying another.

My co-worker Lucinda taught me to hand-sell books when I worked at my uncle’s former shop, Pages Books & Magazines, on Queen Street West in Toronto. Choosing a book to read, she said, is a very personal decision, like choosing what to eat. Bookselling is about watching your customer and listening to them interpret what they’re hungry for. Ask them about what they like and the last book they loved, then lead them to the one that’s next on the web of interest they’ve described (again, you’ve got to know the collection). Put it in their hands — they need to hold it to know they want it — then step back. Give them space to decide whether to bite. Repeat the process if need be. The first berry you pluck may not be right. They need to feel it’s their choice to eat it or not. (But, with room to decide, who could resist such a juicy treat?) Make them feel heard, and they’ll buy the book. They’ll want the conversation to continue.

The craving that pushes individuals to buy and read specific books drives the growth of libraries and archives, too. “Collections are profoundly symbolic of various types of longing,” Concordia University’s Jason Camlot observes in Unpacking the Personal Library: The Public and Private Life of Books, citing his co-editor, J. A. Weingarten, of Fanshawe College, in London, Ontario. Or, as Susan Sontag once put it, a personal library is something of an “archive of longings.” (I discovered a new angle on such longing as I checked the University of Toronto Libraries website weekly for much of the past two years to find out when I could go back. Once the branches reopened, I bided my time before visiting. The fantasy of entering the library, the yearning for it, was more powerful when its promise was forbidden.)

Unpacking the Personal Library is a beautiful edition of sharp academic essays on the intricacies of owning books — an academic work most likely to appeal to students and scholars of information science and book history. Its primary mission is situating the personal book collection within the public library, to explore how such idiosyncratic and storied gatherings fit within broader institutional assemblies of volumes. This is, in short, rarefied turf. The contributors draw out how public collections bear witness to private reading. Ultimately, works in public libraries, Camlot argues, “are all private to some degree insofar as they are the objects of experiential encounters with individual readers.”

Like an edited volume presented as a whole, the voices of grouped books sound together, like the lasting notes of an orchestra playing all at once, a harmony only the collector can hear. Sometimes the notes seem to replicate each other, though, and how many clarinets do we really need playing that C sharp? The question recurs in librarians’ efforts to remove excess copies of a particular title. As the University of Virginia’s Andrew Stauffer points out in his essay on print holdings, however, “we don’t know enough about our collections to de-duplicate with confidence.“

Individual copies of books are not identical enough to view as interchangeable. They’re not coins, and our systems are not detailed or accurate enough to record their real differences. Even trying, Stauffer warns, might backfire, as “developing criteria now for what counts as significant in a particular book risks winnowing the historical record to what we already know how to recognize.” Pulling on this thread leads him to an intriguing logical end: even if we overlook “the outright errors in the scanned pages” of a digitized text, the “ ‘content’— what books contain — goes far beyond words in a particular order.”

The word “content” here is telling. It’s now used less for books than for ideas and creation fed us through the internet, where the walls of the codex have fallen down and a new variety of substance endures. Yet books remain containers for content that can, unlike digital creations, enjoy peregrinations through the physical world that may last longer than their readers. Stauffer’s line of questioning made me think about how readers let out whatever the books contain, and how books leave whichever buildings and boxes contain them.

Sometimes a book found at random is the perfect one, correct as matching boots. The feeling is like seeing a book placed in order on its shelf, findable as it should be, despite the chaos of the world that is always tugging everything out into disorder, disintegration, inexplicable randomness, nonsensical fragmentation. Sometimes the book really is right, fits the slot, and makes a satisfying thunk into the pile, the sound a pat on the head for the good borrower who for once returns loans on time.

In the pandemic, socializing often meant taking out a book and reading it outside or on your phone, in the rain and cold, or not. Rediscovering jumbles of people has been part of the intoxicating return to bar life, a reminder of what weird connections can be made when strangers gather and talk. Like those strangers at the bar, not every book you read at random is the one you were looking for, but it’s still interesting to take a look at the cover, skim the back, flip through with a pause at the beginning, middle, and end for a view of why it might have been this one and not another that spilled itself out from the throng.

As curious about people as I am about books, I can find it hard to accept their anonymity. But now, when strange things happen, as with the boots or the lady in red, I don’t try to determine exactly who the individuals are or what it means that we were thrown together in these unlikely ways. We’re all just books lost in the crowd of the collection, unknown faces in the city whose characters are a bit revealed when we’re gathered together at times and then released. I’ve learned that we aren’t always meant to know each other well; more often we can simply accept the weird gifts of happenstance as anonymous bounty thrown up by the churn of urban life, the collection renewing itself by tossing up some members and then letting them dive back in.

The winter morning after I lost that book, before emailing the piano teacher to ask if she’d found it, I checked the public library’s website. Somehow, Luminous Ink: Writers on Writing in Canada had arrived back at the Lillian H. Smith Branch just a few moments or hours after I took it out, as though the library itself had pulled it home. Little did I know that the same day I lost the book, my daughter had been exposed to the virus at daycare; even as I frantically searched the streets for a missing paperback, my week was about to become a lot more troubled because a tiny virus found us. Circulating in cities means we affect each other as often anonymously as knowingly, as slips and scraps of the material world pass between and among us. Sometimes — oops — we pass a bit of virus to a family member, or sometimes we push a book back in the slot to do a solid for a stranger. The piano teacher told me it wasn’t her.

The book I lost was very briefly out in public — uncontained in the wilderness of Beverley Street, with its hazards of slush and salt and tires. A truly public library would be a paradox, an ordered collection of such footloose titles out on the sidewalks. The real-time digital update on the book’s whereabouts is a feature of what Camlot describes as our current “fortuitous intersection of still-expansive material book holdings at public libraries and fast-developing digital tools for tracking the meaning of such collections.” In fact, we’re all of us poised in this crosswalk, as though online profiles, like entries in a catalogue, made us fully knowable, each of us released in a print run of one but practically interchangeable in the absence of the IRL edition.

There is a weird and secret intimacy in returning a stranger’s library book. I hope that other person with a thing for books somewhere in Toronto felt pleased about their good deed. I would certainly like to thank them for their little gesture of repair of the world and of the collection, for their willingness to pick up a book and carry it to where it needed to go. I briefly wondered whether they were tempted to keep it, but we know enough from the art of bookselling at this point to know they weren’t. Sometimes the wills of people and books just coincide. Writing of a train trip spent reading Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, that famous incunable, Kociejowski describes the “mysterious pleasure when one is able to complete a book within the precise time frame of a long journey.” Sometimes the voyage inside a book reflects the one outside. Sometimes the book travels on its own.

That book I lost wanted to go home, and whoever returned it made its wish come true. That person is my ideal reader, an unknown presence whose impact is felt against all odds, like that lady in red busying herself by buying A Time of Gifts for strangers — an anonymous agent in this moment of broadcast identity on social media, when we’ve all become faces on postage stamps, often messaging no one but ourselves, hoping someone might hear anyway.

The thrilling din of strangers’ voices is what makes bookstores, like cities, so captivating. But sometimes the books themselves gather real-life strangers to each other, sometimes without even letting them meet. I’ve said this before and I’ll say it again: books show us what we have in common with strangers — whether authors, the characters they describe, or the readers you don’t know but agree with anyway. The effort to get out from our own social worlds, our own mindsets, is sometimes matched by the urgent volition of the books themselves to jump out from the collection — and then back in. The crowd reabsorbs its own, the book returns to the library, the unknown person who carried it rejoins the anonymity of the city, and for a moment we can see all the collections of collections upon collections, with each of us just units within them, parts of a bigger whole.

Jessica Duffin Wolfe is a professor of digital communications and journalism at Humber College, in Toronto.