A list of Margaret Atwood’s “shorter fiction” appears before the title page of her newest book. While it helps to locate the volume within her oeuvre, it also confuses other attempts at categorization. “Eclectic fiction” might be an equally fitting way to describe the eight listed works. And such are the fifteen stories in Old Babes in the Wood : reminiscences and histories of varying length, forays into myth and the future, explorations of other species and other ways of knowing.

Divided into three sections and moving between first and third person, these stories visit an array of landscapes, each rendered in Atwood’s characteristically apt imagery: of aging cottages in northern Ontario, of a farmhouse in rural Provence, of ancient Egypt, of a snail’s musing soul. “My Evil Mother,” the middle section of eight stories, is a particularly eclectic mix that is held together by a recurring plaintive tone and that connects the first and third sections, “Tig & Nell” and “Nell & Tig.”

Combined, the Tig and Nell sections comprise seven stories. Nell is an aging writer, while her partner, Tig, appears posthumously in most scenes. His presence is deeply felt indeed. In “First Aid,” Nell remarks that “revisiting sets in, after a time, after many times.” As she revisits their life together, Nell asks the large questions about justice and truth telling that they had always asked, though now with added poignancy — because she no longer fully trusts the answers. In “Two Scorched Men,” a survivor of the Second World War muses to her, “How do we know what is our purpose?” And in “Morte de Smudgie,” Nell notes that “grieving takes strange forms.”

This third story, ostensibly a eulogy to Nell’s cat and a brilliantly funny reworking of Tennyson’s Morte d’Arthur, might seem a departure from the book’s wistful tone. But then we come to the ending: “It hadn’t really been about Smudgie. It had been about Tig. She must already have known on some level that he was bound to set sail first, leaving her stranded in the harsh frost, in the waste land, in the cold moonlight.”

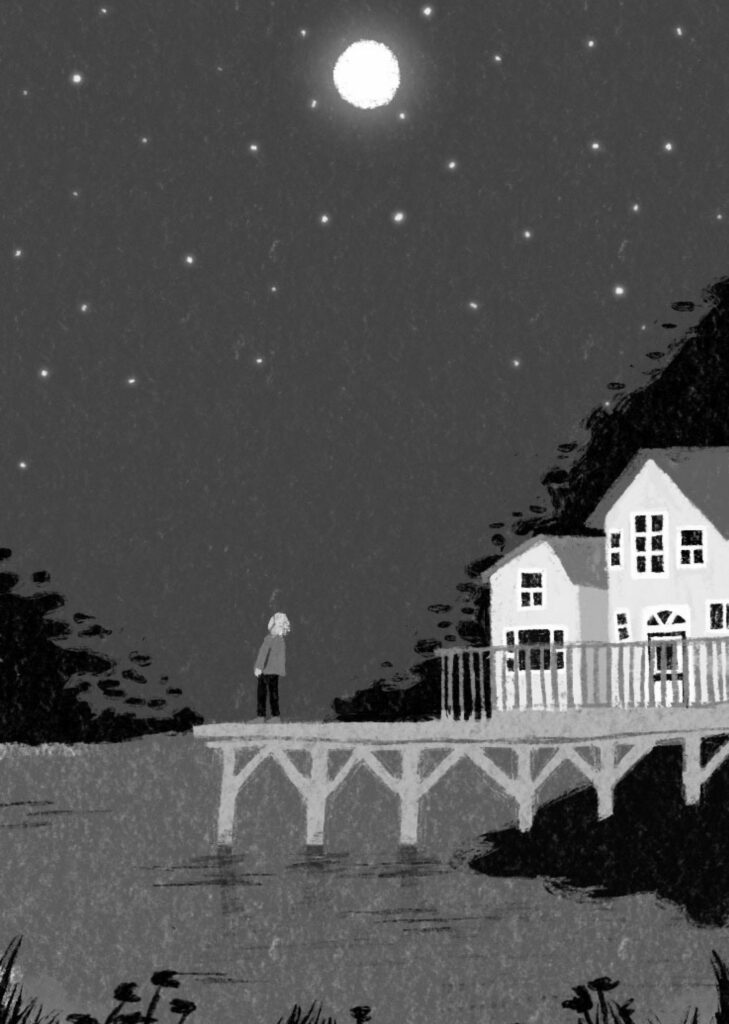

Lonesome nights at the family cottage.

Nicole Iu

Numerous breaks help to shape these stories. At one point, Nell observes her changed perspective on time, now that she’s in her eighties. “There are portals in space-time, opening and closing like little frog mouths,” she explains. “Things disappear into them, just vanish; but then they might appear again without warning. Things and people, here and then gone and then maybe here.” Any sense of security also disappears in the visual gaps on the page.

A persistent search for the right words suggests a kind of purpose, however. Perhaps if the writer could only find ways to describe her experience, she could uncover fuller meaning in it. Myrna, for example, a retired linguistics professor in “Airborne: A Symposium,” confesses that she is “obsessive about words.” She is one of several aging feminists —“obsolete and uncool”— who are outlining the terms of a new endowed chair that will support “younger creatives.” These same women have, at times, felt “scorched” by the words of new feminists. Understanding that they are amid “regime change,” they toast to “rising above it” at the story’s end. “Like the soul leaving the body in the form of a butterfly,” thinks Myrna kindly.

In “Death by Clamshell,” Hypatia is a leading mathematician and adviser to the rulers of fourth-century Alexandria, before she meets an agonizing end: torture by excoriation and having her eyes gouged out. Speaking in the first person, she presumes a reader today might ask, “Was it worth it? My life.” She has yet to find those right words: “I can’t answer that.”

A devotion to finding the right words is also central to the book’s longest piece, “A Dusty Lunch,” which opens the third section. Upon Tig’s death, Nell inherits the papers of her father-in-law, who served as a young brigadier in the Second World War. His experience with the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade emerges through a letter from the war correspondent Martha Gellhorn and “the manuscript of an article on the breaking of the Gothic Line by the assembled Allied forces.” Nell searches for the right “adjectives” for the American journalist: “Practical, sentimental, tough, empathetic, determined. Fearless, though no one is fearless really.” Ultimately, she describes Gellhorn’s reporting as “so fresh, so immediate.” She admires how “the young woman reaches for the right words, how to say it, how to say the unsayable.”

It’s somewhat odd that Nell considers the adjectives “sentimental” and “determined” when thinking of Gellhorn — odd because Nell herself feels that she must battle sentimentality throughout these stories. Can determination adequately balance excessive tenderness?

Tenderness is anything but excessive in “Bad Teeth.” A former magazine writer, Lynne has, over the years, described her friend Csilla as somewhat “underhanded” and “ruthless.” Even as they disagree on memories of the 1960s, Lynne ultimately concedes, “You’re my very dear old friend, and I love you.” Csilla wonders if there’s a “but” coming. “ ‘No but,’ says Lynne.”

In the title story, which also concludes the book, Nell and her younger sister, Lizzie, now both elderly, share days at the old family cottage, where they have spent countless hours over the years. Still fully grieving Tig’s death, Nell states that her heart is broken: “But in our family we don’t say, ‘My heart is broken.’ We say, ‘Are there any cookies?’ ” Making her way carefully to the dock on a clear night to view the stars as he used to do with “such joy,” she feels “only grief and more grief.” But she immediately tells herself, “Don’t be so fucking maudlin.”

Atwood herself appears in “The Dead Interview,” speaking with George Orwell via a medium. Known for (and at times criticized for) his extreme care with diction, the late writer remonstrates: “Change the name of the thing, and in many cases you change the thing.” In a happy diversion at the interview’s end, Atwood cites a recent book by Rebecca Solnit about Orwell’s keen interest in gardening, calling him “enthusiastic about living, full of plans,” and noting that the rose bushes he planted in 1936 are “still alive! Still blooming, every summer.”

Tears come at moments when words fail — not unlike the scent of orange blossoms that appears occasionally or the image of Orwell’s redolent rose bushes. They suggest in wordless ways what Lynne is finally able to articulate: Old Babes in the Wood is a collection of love stories, as mournful as the finest of their kind often are.

Shannon Hengen is a literary critic in Regina.