Fame is a funny thing. People we don’t know will win Olympic medals in Paris this summer and suddenly find themselves at the very centre of things. In an instant, they’ll have become famous — but what’s the point of fame if it doesn’t last?

Nothing had prepared Percy Williams for the transformative moment, measured in fractions of a second as a sprinter’s victory must be, when he became an Olympic champion and a Canadian hero at the 1928 Amsterdam Games. By now we’re used to the idea that fame is a highly desirable commodity, as if it were the motivating factor in athletic performance and the ultimate destination of human achievement. But when the shy, slight twenty-year-old from Vancouver won both the 100 metres and the 200 metres, sudden global attention felt more like a burden than like a reward.

It was the era of the amateur in track and field, when love of the sport was the basis of the ennobled Olympic endeavour and no one could dream of sustaining a career as a runner through fast-food sponsorships or sports gear contracts. Glory was the one gift that an athlete could trade on and live off, the public measure of self-worth that sealed the human connection between a solitary individual in a maple-leaf tank top breaking the tape and the thousands of random onlookers turned suddenly into cheering, adoring fans.

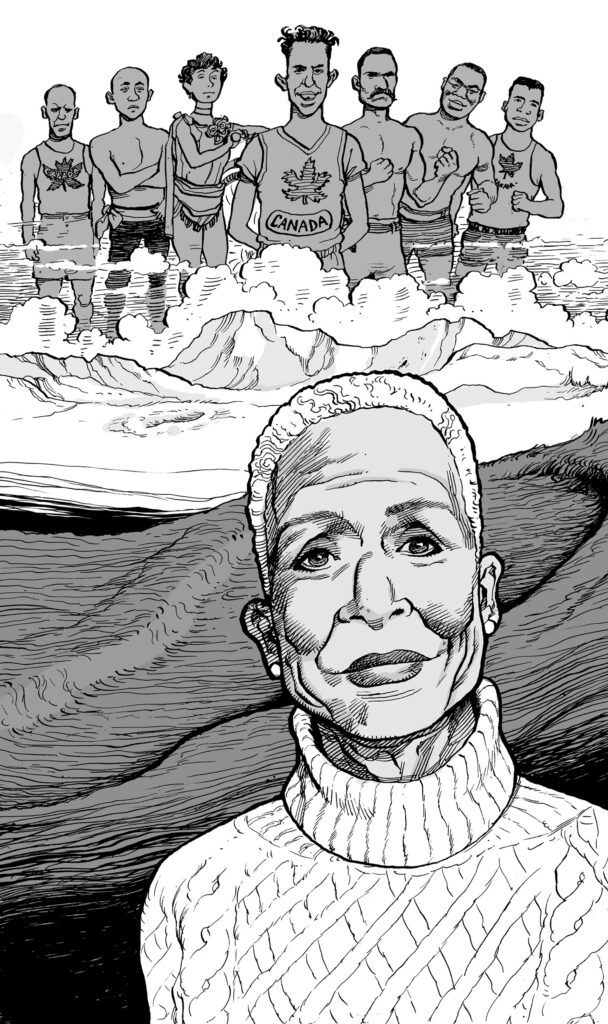

Valerie Jerome and other giants of sport.

David Parkins

How do you harness all that adoration to make it useful — and make it endure? The president of the United States Olympic Committee, no less a figure than General Douglas MacArthur, called Williams “the greatest sprinter the world has ever seen.” To the reluctant, self-effacing speedster, who was just a year away from competing in local high school track meets and ran merely to run, that burst of praise was just empty air. “Well, well, well,” he wrote rather helplessly in his diary after the first victory. “So I’m supposed to be the World 100 M Champion. . . . No more fun in running now.” The finish line was the end point in Williams’s focused, sheltered sporting life when it could have been — and by modern standards of fame, should have been — the beginning.

It wasn’t so much that fame eluded Williams: even in 1928, it was there for the taking. Just a few years later, Jesse Owens would become a legend in the same sport. But in the ambivalent athlete-fan relationship that Jason Wilson and Richard M. Reid describe in Famous for a Time: Forgotten Giants of Canadian Sport, Williams fled his exalted status almost as diligently as he pursued gold, engineering his own disappearance and gradual oblivion. He declined an invitation to attend a special event at the 1976 Montreal Olympics held to honour all living Canadian gold medallists. In 1982, using a shotgun he had been given as one of the few tangible rewards for his success in Amsterdam, he killed himself.

To modern minds, accustomed to the reassuring presence of hallowed veteran athletes in post-career puck drops, honorific induction ceremonies, and nostalgic advertisements that trade on the pleasures of glory-days greatness, this is not the way fame is supposed to end. Being famous, as a purposeful way of life, has become a lifelong project, a busy back-and-forth between athletes and their audience. Travis Kelce, who in his day job is a tight end for the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs, lays down the rules of the game: outsized personality — check; podcasts — check; SNL hosting — check; soup/sandwich/insurance/drug/credit score ads — check; disproportionately famous and omnipresent girlfriend — check. Fame now can be crafted and curated, and it can be sustained as a parallel vocation that is almost independent of sporting achievement.

We inhabit a fame-seeking era when self-generated celebrity has quickly become a be‑all and end‑all preoccupation — and a highly desirable one, to judge from the admiration heaped on people who strive to be not just well known in Warholian increments of renown but grotesquely ubiquitous. At a time when magnitudes of greatness are measured by views and clicks, when the defining human activity has become spectatorship to the lucrative performance art of self-aggrandizing megastars (and their influencer progeny), the connection between being famous and being fameworthy has been irrevocably blurred.

We may overvalue manufactured fame now and not just in crude monetary terms: the worshipful approach to celebrity can’t help but create a dehumanizing caste system for those outside the ropes, however much a Trump rally or a Beyoncé show sustains the illusion that they depend on us, the affirming faces in the crowd, for their success and status. But when we engage with the unpredictable and often unfathomable displays of sport at the highest levels, where extraordinary success and absolute failure are contingent on exceptional human qualities played out against the clock, we recognize from the way our hearts are pounding that we are not wasting our discerning adulation on some transitory TikToker. Spectatorship, at least in sports, is never passive, and that involvement is an essential part of fame’s give-and-take. Who can deny the thrill in seeing a fellow creature suddenly extend the limits of what’s possible? Or resist the breath-holding suspense that’s fundamental to watching an unscripted drama unfold in real time? Or suppress the weird but undeniable patriotic joy that comes from seeing one of our own, whatever that means, triumph against the odds?

That’s why victories and medals and records aren’t enough in the quest for lasting fame: celebrity is a collaborative process, in which an athlete needs to be an active and willing participant. If a javelin falls in a forest and there aren’t 80,000 spectators poised to cheer, isn’t it just some random spear?

Righteous cynics fool themselves into thinking that obsessing over celebrity is the characteristic derangement of technology-fuelled modernity. To the ancient Greeks, who supplied the model for Pierre de Coubertin’s self-consciously refined concept of the modern Olympics, larger-than-life victors deserved universal celebration. Poets such as Pindar, quoted in the epigraph to Famous for a Time, were kept on standby to hymn champions and immortalize their feats. Winners couldn’t — and wouldn’t — hide. Their greatness was fashioned for public display, was designed to be part of something larger and almost religiose: the human need to join in and find vicarious fulfillment in the nearly divine feats of a few.

For large parts of human existence, we’ve been more than happy to exist as patient observers of the fame chasers, watching them clobber a ball, break the tape at a finish line, climb a podium, prance around in a ring or on a stage, rouse a rabble — and this docility would be a disturbing indictment of our own diminished place in the greater scheme of things if it weren’t considered so normal and natural. Wilson and Reid chronicle the backstory of modern Canadian fandom, reclaiming the past glories of sports figures who once captivated the multitude and now — so famously fickle is fame, whatever we choose to believe during the athlete’s unforgiving minute — have bottomed out in the age of Q Scores and X followers.

As a social history of sports amnesia, Famous for a Time offers a litany of forgotten lacrosse players, cricketers, cyclists, high jumpers, and even snowshoe racers who once wowed crowds and who defined the robust image of a young country in search of its distinct identity in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It could serve as a textbook for ambitious competitors seeking their fame and fortune at the upcoming Paris Games — be careful what you wish for, or, less Delphically, have a Plan B — but it is also a stimulating jog through the lost stories and discarded heroes of a sports-loving nation that perpetually moves on from the past. The periodic shifts Wilson and Reid describe in the varieties of individual achievement and collective enthusiasms are rooted in broader sociological trends, political calculations, business priorities, and cultural preferences, and they are interpreted for students of history through the clarifying corrective lenses of race, class, and gender politics. That sounds like heavy going, and a certain self-congratulatory academic attitude to ancestral biases sometimes intrudes on the storytelling. But these gregarious, fame-courting characters of old-time sports are too raucous or quirky to be reined in.

There’s Louise Armaindo, who, after trying out careers as a trapeze artist, circus strongwoman, and race walker, remade herself into a champion high-wheel cyclist, zooming her penny farthing in six-day endurance races before clamouring fans on tiny indoor ovals, beating not just the continent’s best men but even a team of (non-cycling) horses. Or the three Black boxers from the Maritimes who found celebrity and fortune in the pugilistic hotbeds of the fame-friendly United States, becoming the emblematic rags-to-riches headliners of their brutal, lucrative sport: George Godfrey, a former porter and meat carrier, was saluted as “the heavyweight champion of the colored race.” George Dixon, once a photographer’s apprentice, became a featherweight and bantamweight titleholder (interracial matchups in lighter weight classes were considered more socially acceptable) and starred in his own vaudeville show while generating additional income by taking on local tough guys in “come‑all” exhibitions. And Sam Langford, a skinny child janitor and runaway, won the heavyweight championships of Mexico, Britain, and Spain while featuring on the famed “Chitlin’ Circuit” of Black-owned clubs (he was good enough and famous enough that Hemingway claimed to have sparred with him).

And above all there was Walter Knox, often described in the early years of the twentieth century as Canada’s greatest all-round athlete (now perhaps Canada’s “greatest forgotten athlete,” in Wilson and Reid’s words). Knox’s longing for public acclaim led him to enter six different events at the 1907 Canadian Track and Field championships. He won five of them, only to be disqualified because he was discovered to have violated the sacrosanct rules of Olympic officialdom. The modest purity of idealized amateurism didn’t pay the bills, and Knox supplemented his work as a shingle splitter by hustling small-town heroes in high-stakes races before big-betting crowds, defying gun-toting gamblers while competing under assumed names to avoid recognition and elude the arbiters of regulated sport. Before one race in Nanaimo, British Columbia, he was poisoned, but he still rose from his sickbed to best the betting favourite. The losing side twigged to his true identity — such is fame, even when deliberately obscured — and beat him unconscious.

Knox was a rogue. As a coach for the 1912 Olympic team, he predicted a gold medal in the 200 metres for John “Army” Howard, Canada’s first Black Olympian, and then immediately got into a fist fight with his protegé. But Knox’s talent spotting and determination couldn’t be denied. Canada underachieved at the Olympics when its best professionalized competitors were left at home, and the high-minded authorities finally succumbed. Knox was hired by the Ontario government to improve the standards of physical education in the province through technical clinics and training camps, more scientific coaching, and enhanced competition at the elite level, in women’s sports as well as men’s. At the same time, business interests discovered the value in creating sports clubs for their female employees as a way of boosting corporate loyalty in a rapidly evolving marketplace through what was chillingly termed “industrial recreation.” A young woman’s workplace, as Wilson and Reid observe, “became, in every way, central to her life.” Sports was rapidly transformed in step with urbanization, and casual fans became devotees, tracking irresistible success stories as media coverage expanded to feed off the athletes’ bid for fame. By 1928, Canada had become an Olympic powerhouse, winning fourteen medals, and poor Percy Williams was the toast of a nation.

What made Williams such an outlier, sadly, is that he couldn’t bring himself to play to the crowd. But in his prolonged post-Olympic afterlife, when he wasn’t feted with the reverence he felt he deserved, a young admirer appeared who was well placed to appreciate Williams’s conflicted relationship with fame. Not surprisingly, he was a fellow Vancouver sprinter who experienced the vicissitudes of greatness himself.

Harry Jerome, a constant and calming presence in his sister (and fellow Olympian) Valerie Jerome’s painful, brooding family memoir, Races: The Trials & Triumphs of Canada’s Fastest Family, remains better known than his gold-medal precursor. Although his best result over three Olympic Games was a bronze medal in 1964, he tied the 100‑metre record in 1960 when he was just nineteen and went on to become the 100‑yard record holder as well. A larger-than-life statue of the powerful athlete in full flight is a landmark for runners and Instagrammers alike along the Stanley Park seawall. Tracks and track meets, award programs and scholarship funds, recreation centres, and an emerging residential neighbourhood in North Vancouver are all named after him. As a role model for Black youth — one who refused to let racism or disadvantage slow him down — Jerome has attained an immense posthumous stature.

In his short, disordered life, things were not so simple, as Valerie Jerome makes all too clear. The five Jerome children grew up in extreme poverty, neglected and derided by an abusive mother who passed herself off as white despite having a Black father in her rewritten past — and that father, quite amazingly, turned out to be the Olympian Army Howard, an inconvenient truth for a woman who laid claim to being Caucasian even if the family genes helped explain Harry’s and Valerie’s precocious abilities. Fending for themselves from an early age, they had no choice but to face up to the casual racism of postwar Canada on an almost daily basis, only occasionally connecting with their loving but itinerant father, one of a legion of underpaid Black porters who serviced Canada’s passenger trains. The grim setting of their lives, in Valerie’s itemized recounting, is a North Vancouver equivalent of Frank McCourt’s Angela’s Ashes, minus the redeeming mother figure who might have rendered misery more bearable. Valerie’s younger brother, Barton, was intellectually disabled and suffered violent seizures; she long believed his condition was the result of her mother smacking him in the head with a saucepan during an argument. He was institutionalized and sterilized while still a boy. It was a childhood that could have defeated anyone, and Valerie’s amazing attempts to emulate her older brother’s athletic success — at the age of fifteen, she finished fourth in the 100 metres at the Pan-American Games, steps behind the great Wilma Rudolph — were too often sabotaged by crippling anxiety and paralyzing self-doubt.

For all the fine athletes who are forgotten, there are many more who could have and should have been contenders for greatness. Something was missing in Valerie, and it wasn’t talent. Harry called it toughness, the vengeful strength he drew on to power through the barriers life placed in his way. Even at eighty years old, Valerie feels the wounds of racism at every turn. And who’s to say she’s wrong? Harry may have shared her experiences and then some, as a strong, proud, single-minded man of colour, but any anger he felt was distilled into primal motivation. It’s a recognizable trait of top athletes, revving themselves up into an adrenalin-fuelled fury meant to overawe opponents, but Harry Jerome took it to extremes. When he toed the starting line in the 100‑yard dash before a sparse crowd at Vancouver’s Empire Stadium in 1962, no one could have guessed that a fierce argument with his young wife just hours before had left him trapped and struggling under the weight of their U‑Haul trailer. So powerful was his rage after being released by friends that he stormed off to the stadium without his spikes and had to race in a borrowed pair — and he set a world record in the process. “With extraordinary grace of movement, so relaxed and fluid,” Valerie observes, “Harry had taken the energy of an ugly confrontation and used it to accomplish something beautiful. To me, he seemed superhuman.”

And so he was, which was the problem in an environment of constant media encroachment, where everyone wanted direct access while expecting and demanding that he elevate his superstar status to even greater heights. Like Williams, Harry Jerome was too distant and detached to be turned into an everyday Canadian hero, and it became a journalistic trope to describe the world’s fastest man with the resentful and racially charged adjective “aloof,” pointing to a characteristic kind of athletic focus that Valerie viewed more clearly as “the blocking-out mechanism he used to cope with our mother.” Most observers didn’t share her psychological astuteness. When he tore a tendon in the 100‑metre semifinal at the 1960 Rome Olympics, he was quickly labelled a quitter by anonymous team officials and hostile journalists. The empathetic writer Peter Gzowski, no stranger himself to accusations of aloofness, took issue with this smug denunciation of the young, impoverished student-athlete. “It might be pointed out,” he wrote in Maclean’s just before the 1962 Commonwealth Games, “that the men who criticized him are paid to write about what Jerome is NOT paid to do.”

Then the rigours of Jerome’s explosive sport derailed him once more. Having regained his world-record speed, he ruptured a thigh muscle, an injury so severe that he had to spend a post‑operative month in traction with a cast that extended the full length of his otherworldly leg. “Jerome Folds Again,” read the headline in his hometown Vancouver Sun. Amateurism was still the rule on the track, and he had no income to support his wife and newborn daughter. The University of Oregon, where he trained under the legendary coach and Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman (who designed homemade shoes especially for his prize sprinter), stripped him of his scholarship because he was no longer useful. Even his closest supporters assumed his career was finished. After two hard years of rehab and retraining, however, he was the bronze medallist in Tokyo. What drove this driven man?

It definitely wasn’t the rewards of fame or the adulation of uncritical fans. Jerome loved to compete, but, more important, he hated to give up. The gold medal was always in his sights, a tangible link to the reclusive Williams, whose own lifelong aloofness had been softened by the exceptional performance of his young counterpart. In 1959, after eighteen-year-old Jerome broke Williams’s high school record in the 220‑yard dash, the two sprinters were photographed together in the Vancouver Province. Their paths would continue to cross — no surprise when both belonged to the exclusive club of world’s fastest men — and Jerome, perhaps contemplating the fragility of his own future legacy, campaigned to get the publicity-shy gold medallist the recognition he deserved.

Oscar Wilde, who chased fame as a way of life and yet understood its disappointments all too well, said in The Picture of Dorian Gray (or Monty Python’s Flying Circus, depending on your references) that “there is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” Mere mortals are hardly in a good position to understand the mentality of athletes like Jerome and Williams, whose values were so out of sync with the expectations of the crowd, who wanted to let their achievements speak for themselves. But even they must have understood at some point that the cheering stadium didn’t just energize them and give a practical purpose to their highly specialized brand of superiority. It actually validated them. What becomes of Olympian gods when they no longer have worshippers?

Mutual admiration was not enough to sustain the two athletes in their inevitable decline phase. When Williams died by suicide in 1982, Jerome was in a desperate state himself. It wasn’t just that his post-competitive career had ended with a series of mundane disappointments in the drab hallways of sports bureaucracy or that he couldn’t sustain personal relationships or manage everyday tasks with the discipline and zeal and focus he had brought to the track. Worse, for a man whose identity and renown were based on his prodigious physicality, Jerome’s body had broken down. At the age of forty, he began to experience violent seizures and bleeding on the brain, a result, the neurosurgeon speculated, of blows to the head. (Valerie, filled with shame, could not bring herself to tell the doctor about their mother’s violence for decades.)

The seizures worsened. Jerome roused himself from his hospital bed to attend Williams’s funeral — the tribute of one world’s fastest man to another in the afterglow of greatness. A few days later, Jerome was dead himself, choking to death on his own vomit after a final violent convulsion.

The Harry Jerome who is remembered and revered now is in large part a post-mortem creation, a constructive response to his shocking premature death that is at the same time a correction to the dismissive narrative so dominant in his glory days. His fame has been restored, you might say, even if the iconic version necessarily lacks the human qualities that now make this superhuman athlete feel like one of us. Valerie Jerome likely understands why a reader of her book would gravitate toward the most famous member of her family — she is the memoirist who puts her brother at the centre of her story — but her self-effacing manner is as deceptive as Harry’s perceived “aloofness.” She was an Olympian herself, after all, hanging out with the fighter then known as Cassius Clay in Rome’s athletes’ village. Later, she was an inspiring teacher and a hard-working political activist. However much she plays down her own achievements in comparison with his, Races argues otherwise. Her memories of trying to lead a happy and meaningful life in the wake of so much physical abuse, personal cruelty, demeaning racism, and infidelity are almost too painful to read, and that’s why they should be read. So few people who have suffered through the childhood she endured come out the other end able to tell their tale so vividly and eloquently and disturbingly. And if she finally gets to settle a few scores in the process with an all too human sense of triumph, so be it. It’s the privilege of the long-lived memoirist to win her own race.

John Allemang has lost his way in many great cities but now strays closer to home in Toronto’s parks and ravines.

Related Letters and Responses

Valerie Jerome Vancouver