Two and a half centuries ago, the French finance minister Anne Robert Jacques Turgot quipped that taxation is “the art of plucking the hen without making it cry out.” While variations on wording and attribution have circulated ever since (often it’s claimed that an earlier finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, was talking about geese), the lesson has remained consistent: the challenge in government is to find the sweet spot in taxation that will neither scare off investment nor leave a lot of money on the table.

Eric Cline, a former Saskatchewan politician and mining executive, argues in his study of Canada’s potash industry that for more than three decades, following the sale of his province’s publicly owned potash mining company, it’s the people of Saskatchewan who have been well and truly plucked.

Debates over the public ownership of Canadian industry have long been characterized, on one side, by fears that private control of major entities allows most of the proceeds to be siphoned off to global centres of capital and, on the other, by fears that government intrusion in the marketplace will frighten off investors and innovation and lead to stagnation and economic decline. Saskatchewan, which has swung between New Democratic and Conservative (or Saskatchewan Party) governments over the past fifty years, provides a case study of shifting perspectives on public ownership. Since the author was a cabinet minister in the NDP governments of Roy Romanow and Lorne Calvert (at various times overseeing health, finance, justice, and industry and resources), it’s clear where his sympathies lie. It’s also hard to dispute his numbers.

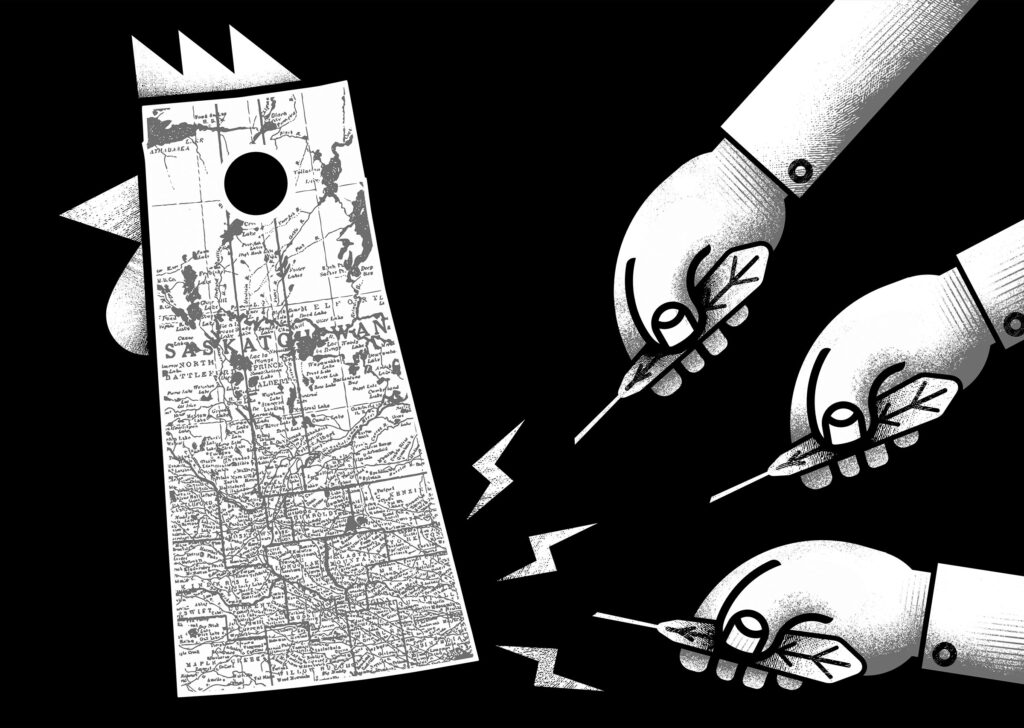

Saskatchewan’s citizens should have cried out when their potash mining company was sold.

Matthew Daley

In Squandered, Cline provides an introduction to the creation of the Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan in 1975 by the NDP premier Allan Blakeney, following disputes over royalties and accounting for extraction of the publicly owned resource: “The creation of PCS as a Crown corporation made it clear that Blakeney and his colleagues in government were people who acted out of principle — as they saw it — and stood their ground.” Over the next three years, PCS negotiated to buy four mines outright plus a majority stake in a fifth. These acquisitions made it a big enough player to have an influence on global markets for potash, which is needed to produce fertilizer for crops. Cline quotes a study, by the economist Nancy Olewiler, which showed that PCS provided after-tax returns to government of 23 to 34 percent per year from 1979 to 1981. “On an equity investment of about $420 million,” he writes, “it made profits of $78 million in 1979 and $167 million in 1980.”

Like any commodity industry, the potash business goes through ups and downs. High prices have prompted investors to open new mines, leading to increased supply and lower prices. The industry might make big bucks one year and be in the doldrums a few years later, and neither result can be attributed to the quality of management decisions. Cline is harshly critical of a 2017 study by the right-leaning Frontier Centre for Public Policy that examined the effects of privatization of Saskatchewan’s potash industry. In it, the analysts Mark A. Moore and Aidan R. Vining compared four years of PCS’s operation as a Crown corporation, during a time of depressed potash prices, with twenty-one years as a private business, during a time of steadily increasing global demand. “On this strange basis,” Cline writes, “the authors conclude that privatization increases efficiency and profits over time.”

The defeat of the Blakeney government in 1982 brought Grant Devine’s Conservatives to power, and with them came an ideological opposition to public ownership. Devine and his colleagues left PCS “under the thumb of its competitors,” in a consortium known as Canpotex, hampering the company’s ability to expand its market share. A larger market share was necessary to justify a planned mine expansion.

After seven years of operating under a provincial government that Cline says hamstrung its effectiveness, PCS was unloaded in 1989. A public corporation with “assets with a replacement cost in the billions of dollars was sold by the Saskatchewan government for approximately $630 million,” he writes. As time went by, the deal looked more and more lopsided. By 1997, the now privately owned PCS was worth $4.5 billion (U.S.). In 2010, the Australian mining giant BHP offered nearly $40 billion (U.S.) for it in an unsuccessful hostile takeover bid.

While potash continues to support the Saskatchewan economy, through 5,100 industry jobs and through royalty fees for the publicly owned resource, the chasm between the sum the province received for PCS in 1989 and the company’s later value supports the use of the word “squandered” in the book’s title. Cline quotes Erin Weir, an economist for the United Steelworkers at the time, who estimated that by 2011 foregone revenue as a result of privatization had cost the people of Saskatchewan between $18 and $36 billion: “Weir argues the 1989 sale of PCS ‘was the worst fiscal decision in the province’s history.’ ”

Cline also details insult added to fiscal injury. The privatization deal was meant to ensure that PCS’s head office stayed in the province, but it appears to have been a Potemkin C‑suite. The CEO sold his “sprawling riverfront home in Saskatoon” in 2002 and moved to the Chicago area, where a majority of senior executives lived by 2010. At one point, the CEO claimed a modest company-owned Saskatoon condo as his residence in order to prove the company’s Saskatchewan bona fides.

Despite having a minimal head-office commitment to Saskatchewan and Canada, PCS waved the Maple Leaf at both the provincial and federal levels when BHP attempted its takeover, prompting government opposition to a deal. Years after that failed bid put the value of the company at $38.6 billion (U.S.), PCS accepted an offer for about a third of that amount to merge with the Calgary-based fertilizer manufacturer Agrium. The $14-billion (U.S.) deal led to the formation in 2018 of Nutrien, headquartered in Saskatoon.

After tracking the rise and fall of publicly owned potash mining and demonstrating the bonanza that followed for the investors who paid Grant Devine’s fire-sale price for PCS, Cline delves into the income lost to Saskatchewan since potash prices began rocketing skyward. After selling for $286.71 per tonne in 2007, potash bounced between $373 and $809 over the next fourteen years. A huge jump in 2022, up to $1,334, was fuelled in part by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“Clearly, increased profits to potash producers after 2007 occurred mainly because world market prices rose, not because of increased investment, assumption of risk, or increased output from the potash companies,” Cline writes, arguing that the windfall should have gone first to the owners of the resource: the people of Saskatchewan. Instead, the province’s share of revenue generated by potash sales has varied from 37.7 percent in 2016 (a down year for the industry) to 24.6 percent in 2022.

As Cline notes, Canada is the world’s largest exporter of potash, producing and selling more than 30 percent of the global supply annually (compared with Russia’s 20 percent and Belarus’s 18 percent). In 2022, Canada produced $18 billion worth of the mineral. He contrasts the bargain royalties that Saskatchewan charges to the way Norway has handled its petroleum reserves: its government-owned oil company, Equinor, contributes to a sovereign wealth fund now worth some $700 billion (U.S.).

Given the supply, quality, and accessibility of its potash reserves, Cline argues, Saskatchewan should have played hardball. Companies simply cannot afford to be shut out of the province.

In his discussion of forfeited profits, Cline cites the concept of “economic rent,” defined as any payment in excess of the amount needed to bring something into production. In classical economics, profits made through economic rents are considered unearned, unlike those made through productive effort or innovation. If mine owners were able to cover their costs at $286 per tonne, for example, the extra money they made when prices rose would be economic rent: unfair gains for investors.

Cline certainly doesn’t come across as Hugo Chavez in a Roughriders jersey; he’s not calling for the province to seize back control of the mines and their profits. But after reading the long lists of company profits and provincial revenues from this spectacularly valuable industry, it’s hard not to agree with another politician, Jimmy McMillan, a perennial candidate in New York City. McMillan’s all-purpose political slogan — and the name of his party — is “The Rent Is Too Damn High.”

Bob Armstrong is the author of Prodigies, an award-winning Western, and, since 2002, the speech writer for Manitoba’s lieutenant-governor.