At its core, Transplant is a book about humility. The title references both Arvind Koshal’s work in heart transplant surgery at the very birth of this specialty in Canada and his somewhat unanticipated immigration from India. When Koshal travelled from Raipur to Ontario in 1975, to enter a residency program in general surgery at the Ottawa Civic Hospital, he fully intended to go back, eventually, to work as a surgeon. But then his commitment to his surgical training and his skill caught the attention of the chief of cardiac surgery, Wilbert Keon.

Keon had recently founded the University of Ottawa Heart Institute, where, a year after he arrived, Koshal became the first trainee in cardiac surgery. He went on to become a staff surgeon at UOHI, when his new field was still in its infancy. In 1991, Koshal became the chief of cardiac surgery at the University of Alberta Hospital in Edmonton. Throughout his career, Koshal has valued the fact that patients in Canada receive care in an “egalitarian” manner, with no regard to their social status, in contrast to what he had seen growing up in India. Along with others, he lobbied for what would become the Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute, which has provided expert cardiac care to both adults and children since 2009, increasing access for people across Western Canada and the Far North.

The tale of how Koshal — with curiosity and skill, plus a little luck and fortunate circumstances — helped build robust cardiac surgery programs in both Ottawa and Edmonton is also an immigrant story. He recalls his own “transplantation” to Canada with a tremendous amount of modesty and humour. Koshal is a natural storyteller — and a charming one at that.

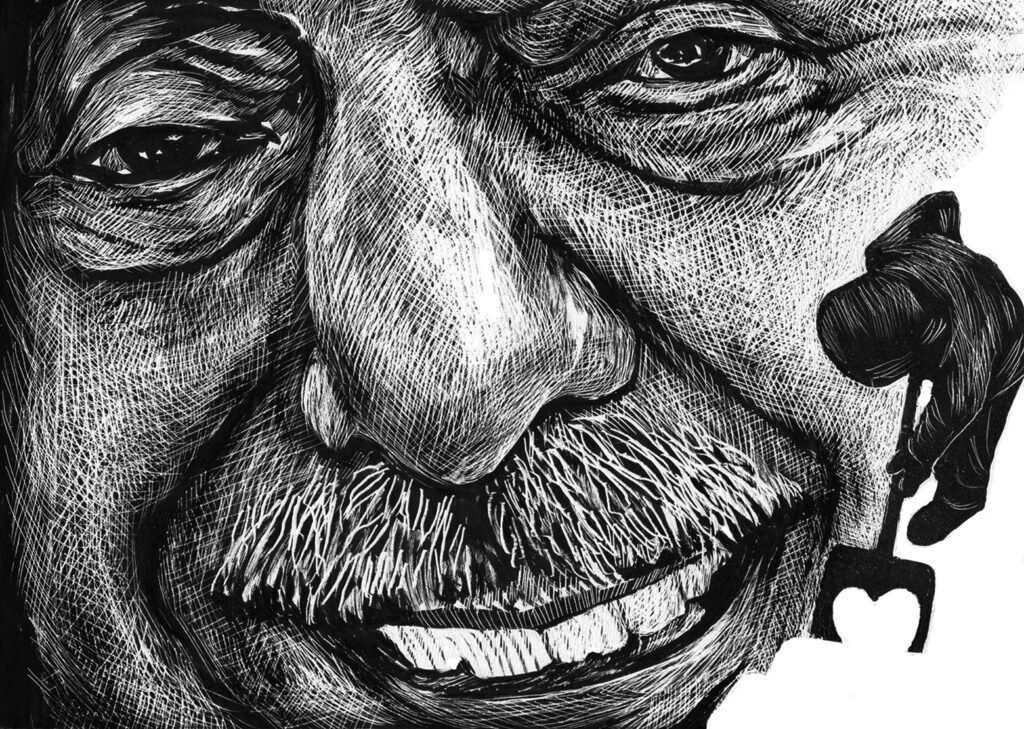

The immigrant who helped clear the way for modern cardiac surgery in Canada.

Silas Kaufman

The strength of this memoir resides in the author’s appreciation for those he has encountered in his life and his palpable determination to accept opportunity when it presents itself. He begins by describing the simplicity of his childhood in Gwalior and Jabalpur, recounting memories of his mother and sister as well as his father, also a surgeon. “In line with the prevailing customs of well-educated households,” Koshal writes, “we employed two full-time maidservants.” Although paid workers, these women “became integral members of our family.” Notions of class and, especially, mutual respect recur throughout the book. “When you become a cardiac surgeon, you have to set the rules,” Koshal remembers telling a resident years later, after the younger man snapped at a nurse. “You can’t be rude to the staff. It’s unacceptable.”

Integration into Canadian society did not always come easily for Koshal and his wife, Arti. In relating how they became successful “transplants,” he captures the amusing inelegance that often accompanies the migrant experience, from learning how to navigate Ottawa’s public transportation system in “menacing” weather to shovelling a driveway for the first time. “What did I know about snow?” he recalls.

Although less humorous, Koshal’s history of cardiac surgery in Canada is an astonishing one. He recounts the implementation of various technologies as well as the human ingenuity that went into providing novel forms of care for patients in an era that is all but unimaginable for many medical practitioners today. Indeed, the courageous work undertaken in the 1970s and ’80s constituted the building blocks of what would become ubiquitous surgical strategies to arrest cardiac disease. Koshal rightly praises the purposefulness that went into building our current system, especially “the dedication, expertise, and unwavering commitment” of its people.

Particularly captivating is Koshal’s retelling of the first artificial heart transplant in Canada, on August 15, 1986. Koshal was part of the team that kept a forty-one-year-old patient, with a “total blockage of her left main coronary artery,” alive with an implanted Jarvik‑7, “an extraordinary invention.” Koshal recalls that initial operation and the subsequent human heart transplant with a disarming style, conceding some seat-of-the-pants moments, like an episode in which he had to outsmart a hospital security guard skeptical of a cooler and its “precious cargo.” This is less an arrogant surgeon convinced of his own powers and more a self-aware pioneer navigating undiscovered terrain.

Like Arvind Koshal, I had South Asian parents who taught me the importance of education, hard work, and making a difference. I also grew up in the developing world, where housekeepers were common and extensions of our parents, where fresh fruits brought as much excitement as celebratory holidays. We both left our home countries and immigrated to Canada to study and work in health care. Like Koshal, I have enormous gratitude for having been able to do both. And I take tremendous pride in my work with patients at Koshal’s former hospital in Ottawa.

While people are not necessarily bound by geography the way previous generations were, we remain defined, in so many ways, by the culture we grew up with. An immigrant’s challenge is to understand what portions of their homeland’s culture they should preserve and what portions of their new country’s they should adopt. The adversity that many experience along the way can diminish overall well-being and life satisfaction. In other words, immigration and vulnerability go hand in hand, and in this sense Transplant is not unique. What is unique is how Koshal presents his groundbreaking work as a cardiac surgeon once he got here: not as a story of struggle but as one of transformative opportunity.

Menaka Ponnambalam is a nurse practitioner at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute.

Related Letters and Responses

Marc Ruel Ottawa