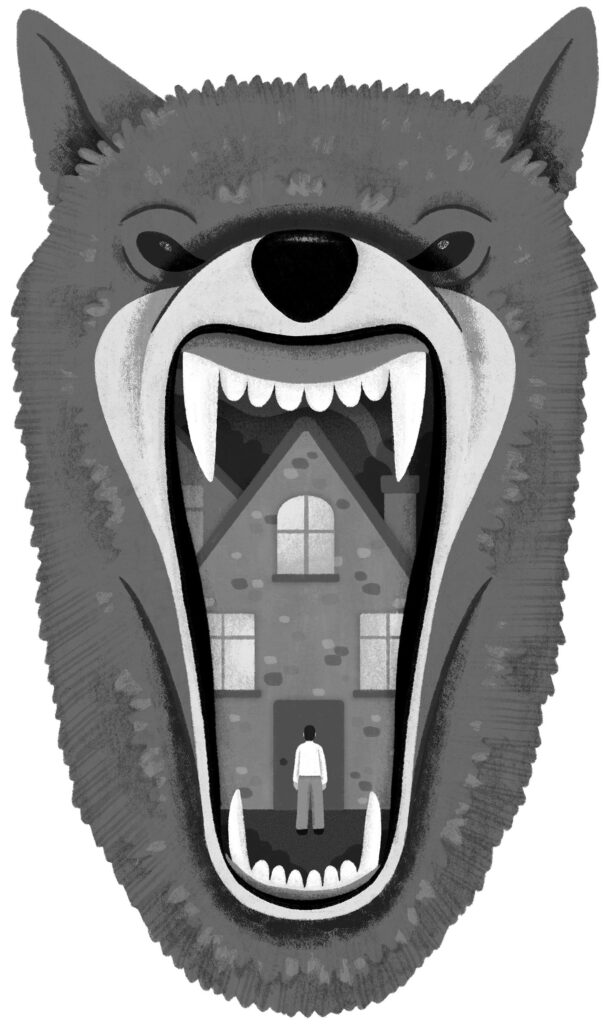

The unnamed narrator of Hides realizes his mother is dead by touching her. “It is not enough to say that the hand had grown cold, though it had, very cold, in fact,” he recalls, “but the veins themselves, the gentle throb of blood coursing across her papery, liver-spotted skin, seemed depreciated — flattened.” Rod Moody-Corbett’s remarkable debut is about the protective walls that go up as we age, grieve, and endure change. Throughout the novel, skin is fragile, tough, thin, smelly, “ragged and hairy,” peeled, and illusory. It is a faulty layer between the true self and the outside world. With this salient, sagging symbol, Moody-Corbett writes an unflinching portrait of male friendship as it ages.

The story begins in a moment of indecision. A middling academic in Calgary — whose rambling and florid prose reveals both his alcoholic and his literary tendencies — begrudgingly considers returning to his native Newfoundland and Labrador for an October hunting trip. Organized by his old friends Willis and Baker, along with Willis’s younger son, Isaac, the week-long stint at a backwoods lodge marks the anniversary of the death of Willis’s older son, Travis. The English teacher thinks hunting is an absurd way to commemorate Travis, who was fatally shot during his third year of university in Alberta. Although he has no kids of his own, he had taken to his friend’s son. Pacing in his apartment, he runs through memories: Travis’s arrival in Calgary, their errands around the city together, Travis running the 5,000m in the Olympic trials, the night of the shooting, the day of the funeral. “Does it have to be guns?” he pleads on the phone to Baker. But with no excuses beyond his mid-semester commitments to a few introductory classes, he reluctantly agrees to join.

Beyond the getaway’s hypermasculine facade.

Paige Stampatori

Between thoughts of Travis and wading through his own inner turmoil about going home, the sessional lecturer browses a creepy website for the “chaperoned hunting” packages offered by the Castle, an upscale self-sufficient compound. The expedition, selected and paid for by Willis, will be somewhere in the Castle’s 200 square kilometres of distant wilderness, with a wide range of game (harvesting overpopulated coyotes is gratis). Their jumping-off point will be the Castle’s seafront resort, a centre for luxurious off‑grid living —“less hunting lodge than bougie meditation retreat.” He peruses the arsenal of available weapons, “marvelling at the raw eroticism of break and bolt action rimfires”; scans the celebrity endorsements (Werner Herzog is a frequent visitor); and reads about the eccentric founder, Judith Muir, and her sponsors. Don DeLillo’s influence is felt throughout Hides but perhaps most notably in the opening pages, in which a magnificent, dangerous institution intrudes upon the life of a character who is as intelligent as he is anxious and self-destructive.

The narrator arrives in St. John’s a few days early to see his father — with whom he’s had a strained relationship since his mother’s death. His misgivings about his dad mirror his diminished connection to his home province. He strives to keep his life (and mediocre career) out of view from his friends and family, explaining that “living away, and staying away, keeps me — or to press the matter with a degree of finitude: the idea of me — safe.” On his first night in town, he goes on an impromptu bender with Baker, who, unbeknownst to his enabling friend, is trying to stay sober. Baker ends up in the drunk tank, and the next morning he drops out of the trip altogether. To the chagrin of the narrator, his father steps in to take Baker’s prepaid spot. “The unvarying maleness of our expedition, oppressive from the first, had grown ever more unsettling in light of this latest Lear-like charade,” he says. “There was too much nature in this, altogether too many fathers and sons.”

Existential, geopolitical, and environmental anxieties converge at the Castle, producing an atmosphere of distrust and claustrophobia. The hunters cede their phones on the evening of a federal election. After an afternoon at the shooting range, enigmatic Judith reveals to the uneasy narrator that some of the small animals running around are actually surveillance tools equipped with cameras. The next day, the founder herself leads them to a cabin in the bush, where they begin their multi-day hunt. One evening, after some pressing, she reveals that a major oil spill, along with the demise of her first marriage, motivated her to build the intensely disconnected complex. She wanted to create an environment that existed outside of destructive male-dominated systems — one that would be entirely self-sustaining, even if that seemed apolitical. “There is nothing, no election here, no politics. The absence is itself political, obviously,” she tells the group between inhales from her signature wooden pipe. “But this is not a heavy absence, not a weight. It’s the absence of men’s power, that’s the thing. A refuge from those patriarchal manacles.” The former ornithologist recalls the distinctly man-fuelled rage that drove her away from her career and into isolation. “The spill was man-made, was male,” she says. “All spills, all wars, are.”

Judith’s monologue marks a shift in the novel. The hypermasculine facade of the cabin crumbles and gives way to a nuanced critique of masculinity, while the narrator feels his own shoddy exterior wearing down. The hunt culminates in a fight in which Willis lays bare his friend’s insecurities and faults — from his addiction issues and temper to his personal and professional failures. He trembles in response, unable to explain why he hasn’t been more supportive since Travis’s death. Willis punches him in the face and leaves him bleeding in the forest. Later, the struggling intellectual realizes his friend is right about the violent effect of his apathy: “ ‘There’s something sinister in you,’ Willis had said; I wasn’t sure I disagreed.” He reflects on the pathetic state of his life, his dark and deleterious behaviour, and his futile attempts to hide from his loved ones. “I’d hardened, grown steadily more cynical and remote. On this Willis wasn’t wrong,” he finally admits to himself. “Where once I infused a sense of calm, soothing feuds and mending frayed feelings, now I seemed a perilous agent of chaos, an agitator of abject brawling, silence, and spite. What’d happened to me?”

Despite feeling, at times, overrun with metaphor, Hides is a staggering exploration of the way indifference festers, solidifies, forces us into exile — be it physical, moral, intellectual, or otherwise. From the perspective of an unforgettable narrator, Moody-Corbett considers how we age into complacency and, more importantly, what it takes to heave oneself out of it.

Emily Mernin is an associate editor at the Literary Review of Canada.