In Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, Septimus Smith has trouble crossing the street. Set over the course of one day, the narrative follows the shell-shocked veteran as he battles with flashbacks to the First World War. His wife, Rezia, chaperones him around London in search of a distraction. When a car backfires, pale-faced Septimus feels everything stop: “The world wavered and quivered and threatened to burst into flames.”

Adam Dumont, the protagonist of Fanny Britt’s Woolfian Sugaring Off, suffers from a shell shock of his own, though his PTSD stems instead from a distinctly modern episode. For the forty-seven-year-old chef and television host, a trip to Martha’s Vineyard quickly turns from a luxury vacation into a personal hell. While attempting to surf, he collides with Celia, a local teenager, leaving her with a severely dislocated knee and a hefty medical bill. In the following days, Adam oscillates between shame and anger, shifting the blame from himself to the victim and back again, until he finally asks himself, “Wasn’t she entitled like everyone else to enjoy the beach without wondering if some thrill-seeking idiot would have so little control over his board?”

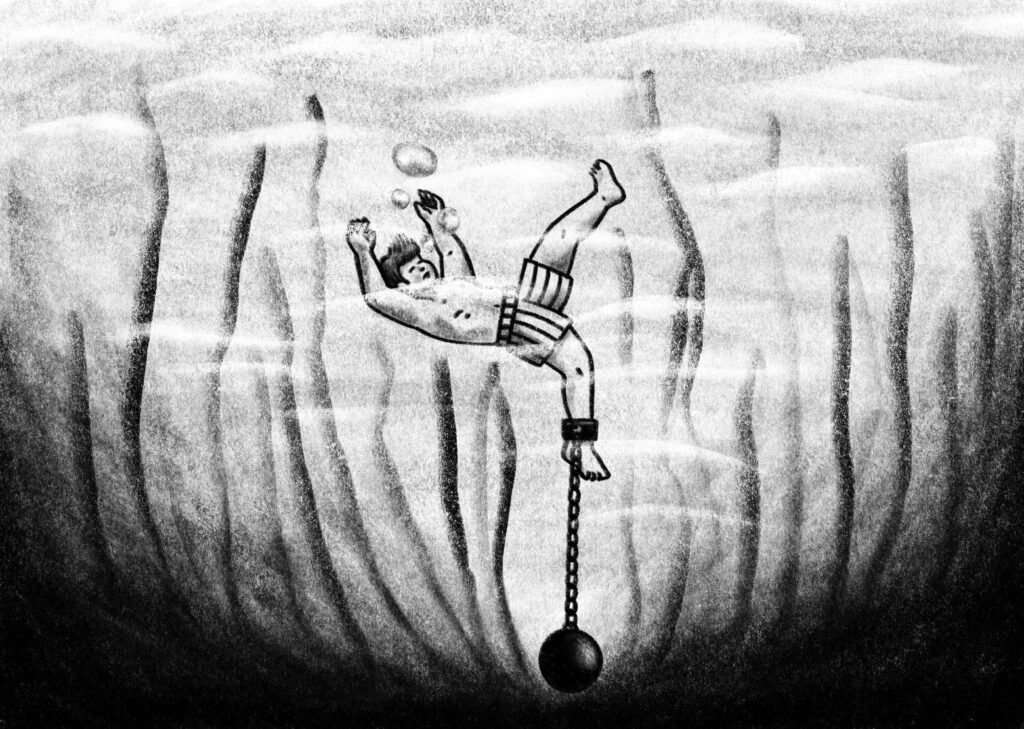

The beach collision catalyzes a mid-life mental breakdown. For weeks, Adam can’t sleep, work, or shake the “troubling sorrow that weighed on him.” He obsessively relives brutal scenes from the crash, remembering “the rough contact with the board, the wave that swept him under, the sand that slid beneath the lining of his bathing suit, the undertow tugging at his body, neither ocean bed nor surface for endless seconds.” In the aftermath, his remorse festers and worsens, fuelled by the realization that he walked away without any serious physical injuries.

Weighed down by privilege and guilt.

Gwendoline Le Cunff

Readers also gain insight into how Adam’s girlfriend, Marion, is affected. After the accident, she comforts Adam as he sobs. But she quickly tires of his dramatics, and her sympathy is replaced with bewilderment: “How had it come to this?” She refuses to see her boyfriend as traumatized; she thinks the incident was alarming but not worthy of the “loud, high-pitched sobs” he cried on the beach nor of the ensuing weeks of strange behaviour. As time passes, she feels increasingly alienated from his new, guilt-ridden personality. While Adam and Celia alternately question what it means to be a victim, Marion wonders what role we should play when a loved one is suffering.

Adam might be a purely sympathetic character if he were not the picture of excessive privilege. His flippant, uncritical relationship to wealth becomes obvious once he and Marion are back at their home in Hudson, an affluent suburb of Montreal. Standing in the kitchen of his upscale home, he looks down to the fields below and agonizes over a new power line that interferes with his view. As he does over the run‑in with Celia, he obsesses over this “disfigurement” and the loss of control it represents.

Britt deftly uses a stream-of-consciousness technique to explore the schism between people’s innermost thoughts and their actions. Her writing is introspective, with language that packs emotional heft while capturing deep interiority: musings, feelings, and anxieties that most people wouldn’t dare articulate out loud. Mid-conversation, Adam digresses internally, and the reader is privy to the difference between what he says and what he thinks. Upon meeting the kind owners of a family-run maple sugar stand, he’d like to open up to them. “I just about died this summer,” he imagines saying, “and ever since I’ve had trouble sleeping; I fall asleep exhausted, wake up with a start, terrified, on the verge of drowning, my heart racing.” Instead of exchanging niceties, he wants to tell them that he’s “acutely aware of the finite nature of things, the impermanence of any possible serenity, and that observation hurts.” But he struggles in silence.

In Sugaring Off, Britt examines the psychologies of Adam, Marion, and, to a lesser extent, Celia. The book could have been balanced with more from the victim’s racialized perspective, which is in stark contrast to that of the rich white couple. In addition to the bookending chapters focused on Celia and her recovery, there’s a short one toward the end that feels misplaced. In it, her life is quickly outlined: her excellent academic reputation, her absent father and sick mother, and the economic downturn on the island. This brief foray into her world before the accident is far less developed than Adam and Marion’s backstory. Without a thorough understanding of Celia, the seemingly climactic final chapter falls noticeably flat.

Still, Britt’s empathetic prose, translated from French by Susan Ouriou, makes a case for sympathy toward Adam despite his superficial advantages, while also showing the wide-ranging effects of trauma. The nature of his romantic relationship — and the role that guilt, complicity, and wealth play in it — is laid bare for readers to scrutinize and challenge. In Mrs. Dalloway, Rezia, while shepherding her husband through the city, is hopeful that Septimus might be healed by the beauty of something. “But beauty was behind a pane of glass,” Woolf wrote. Similarly, Sugaring Off reveals comfort to be an illusory commodity that, once gone, becomes nearly impossible to access again. No one is untouched by pain — physical, emotional, or any other kind.

As Adam’s tailspin progresses, Marion shifts her focus to herself, allowing a chasm to open between them. Britt’s astute character study of the couple underpins a criticism of class privilege that is as complex as it is incisive.

Emily Latimer is a freelance journalist based on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia.