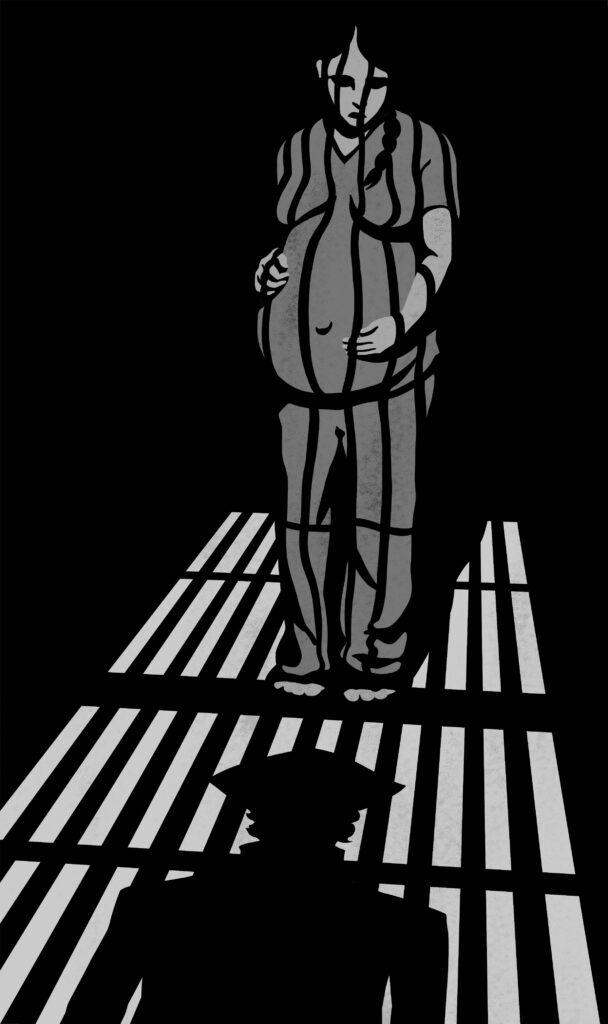

The allegorical figure of Justice, with her scales and sword, was first blindfolded in the sixteenth century, and today she is seen as an embodiment of impartiality: a weighing of evidence and arguments that is unmuddied by prejudice. But some detect a much less noble reason for Justice’s covered eyes: they represent the system’s blindness to abuses right under its nose. Robin F. Hansen would likely agree. With Prison Born: Incarceration and Motherhood in the Colonial Shadow, she examines automatic mother-child separation and highlights abuses both personal and procedural. In doing so, she helps loosen the tightly tied blindfold of racial and gender bias to show that such policies have “no place in a fair legal system.”

Every year, an estimated minimum of forty-five women in federal and provincial prisons give birth to babies they must then leave behind. The mothers are escorted back to their cells and sentences, and the newborns, with obviously no say in their fate, are mostly sent into foster care. Without due process, “the judge sentences the newborn.” Key here are the terms “estimated” and “mostly,” because consistent records are simply not kept — just as court decisions that incarcerate expectant mothers, despite the availability of non-carceral options, are often oral judgments rather than written.

Rooted in the case of “Jacquie,” whose appeal Hansen worked on in 2016, the book’s early chapters include a first-hand account of medical neglect, labour in leg shackles, and the traumatic prospect of having one’s baby taken by the state. (Alternative sentencing was eventually arranged for Jacquie, which allowed mother and child to stay together.) Hansen then broadens out, identifying and dissecting colonially entrenched and androcentric norms that compromise the fair treatment of Indigenous women, like Jacquie, who are so overrepresented in the “ ‘white’ settled space” of Canada’s criminal justice system.

Due process eclipsed by a colonial legacy.

M.G.C.

An associate professor of law at the University of Saskatchewan, Hansen is an expert on the construction of legal personhood. Many of her articles — in Canadian Journal of Human Rights, Global Jurist, The Modern Law Review, and elsewhere — concern trade and investment law, as well as the status and behaviours of multinational enterprises. Although we might hope we wouldn’t need to discuss legal personhood when it comes to actual persons in twenty‑first-century Canada, this book suggests that we still do.

Hansen began researching the topic of prison-born children in 2014, before ever meeting Jacquie. She had come across a case touching on the termination of a British Columbia correctional centre’s long-standing mother-baby program, which the provincial supreme court reinstated after concluding that the closure violated several Charter rights. Hansen, then pregnant with her second child, was “appalled” by the attempt to end the program: “These decisions showed a chilling disregard for children’s welfare, deep disrespect for women, and bald ignorance of what it is to care for someone during early infancy.” With both empathy and analysis, Hansen digs at the roots of this discrimination. While she uses systems theory and concepts of spatialized justice, readers don’t need to absorb specialized terms to follow her argument. Writing with the procedural, logical tone of a scholar ensuring that her points are solid, clear, and backed by evidence, Hansen traces how Canada’s legal system, despite ideals of impartiality, is grounded in “conceptions of space that deny or subvert Indigenous humanity.”

This “purposeful blind spot,” she wants readers to remember, is not in the distant past. Hansen makes sure to frequently reground us in the various biases that shaped Jacquie’s experience and the experience of others who have had their rights — and sometimes their lives — trampled by various elements of the justice system.

Systemic discrimination is about perception; it hinges on “ways of seeing persons and spaces.” How are Indigenous women and Indigenous parenting viewed and valued? Are criminally convicted women automatically deemed unfit mothers? Are Indigenous children still seen as better off under state care? What are the other options? Together, the legacies of residential schools, the Sixties Scoop, medical and nutritional experiments, and birth alerts reveal how deeply “the colonial lens dehumanizes Indigenous children as chattel for the taking.” The stakes for consciously changing perceptions simply couldn’t be higher: “The sanctity of human life demands it.”

In her final section, Hansen looks at which measures would actually pass the sniff test in the case of Jacquie and her son. “If colonial lens and androcentric lens expectations are rejected,” she asks, “is automatic newborn-mother separation actually legal in Canadian and provincial law?” Here she demonstrates a deep respect and passion for both people and process.

At times, it could seem that Prison Born misses opportunities to hear additional human stories: through the voices of women who had their babies taken or in a glimpse of a functioning mother-child prison unit and its benefits to all involved. But that’s not Hansen’s project. Drawing upon her legal training and multiple access-to-information requests, she methodically examines what’s happening, why it’s happening, and why it’s morally and legally wrong.

Such thoroughness builds convincing arguments, even if it slows down the reading. Peeling back the many layers of bias at play results in considerable overlap, often with overviews of well-known topics that risk making the impatient reader say, “Yes, we know that.” But this type of casual reaction should remind us what we likely know all too well: that these cultural thought patterns are so ingrained that we need to see them in the aggregate in order to recognize how insidious and harmful they are. The repetition, if we allow ourselves to be shown our own blinders, reinforces how much work still needs doing. As Hansen puts it, “The legal system exists only as we make it.”

The book’s dedication reads simply, “For the people who change this.” That sets a powerful tone: automatic mother-child separation is an unseen and unnecessary crisis that needs not just awareness but action, and readers must ask themselves, “Does she mean me?” Indeed, as Prison Born spotlights the need for procedural and systemic improvement, it challenges us as individuals to take off our own blindfolds.

Amy Reiswig writes on topics ranging from dance films to Faroese Viking metal.