Hélène Dorion’s Not Even the Sound of a River arrives in English heavily garlanded. The author of more than thirty works of fiction, poetry, and non-fiction, Dorion has won a basketful of prestigious prizes within and without Quebec, including a Governor General’s Literary Award. A book of her poems, Mes forêts, is in the curriculum of France’s baccalaureate, making her the first living woman and Quebecer with this honour. The French version of Not Even the Sound of a River, published in Quebec in 2020 as Pas même le bruit d’un fleuve, was a bestseller and a critical success.

In this highly wrought, layered book, the chapter titles often reference other works — for example, “At the end of the suffering there was a door” alludes to a poem by Louise Glück — all of which are identified in an author’s note at the end. Dorion also created a companion Spotify playlist of the music she listened to while writing, from Laurie Anderson to Henryk Górecki. If that sounds intimidatingly or irritatingly precious, do not fear. The absorbing story of three generations of women moves back and forth along the St. Lawrence River, from Sainte-Luce-sur-Mer in 1914 to Montreal in 2018. Eva’s fiancé dies in the First World War, in 1916, and she settles for an unhappy marriage with Édouard, a mild-mannered alcoholic. Simone, the daughter of Eva and Édouard, loses her great love, Antoine, in 1949, and she weds Adrien, a man for whom she feels little or nothing. Their daughter, Hanna, becomes a writer. Eager to distance herself from her melancholy, elusive mother, she has a brief marriage and a string of broken romances.

Brought up by a parent who refused to reveal herself, Hanna believes that those closest to us remain “unfinished mosaics.” When Simone dies, Hanna thinks, “She took away everything, starting with the story that in a sense was my own.” But, unexpectedly, as the daughter sifts through boxes of papers and photos left behind, the mother starts to come into focus. “For her it was the end,” Hanna realizes, “but for me something was beginning.” The archive reveals the passionate love affair Simone had in her twenties with Antoine, a man old enough to be her father. After it ended tragically and mysteriously, she lived hidden in her sorrow for the rest of her life.

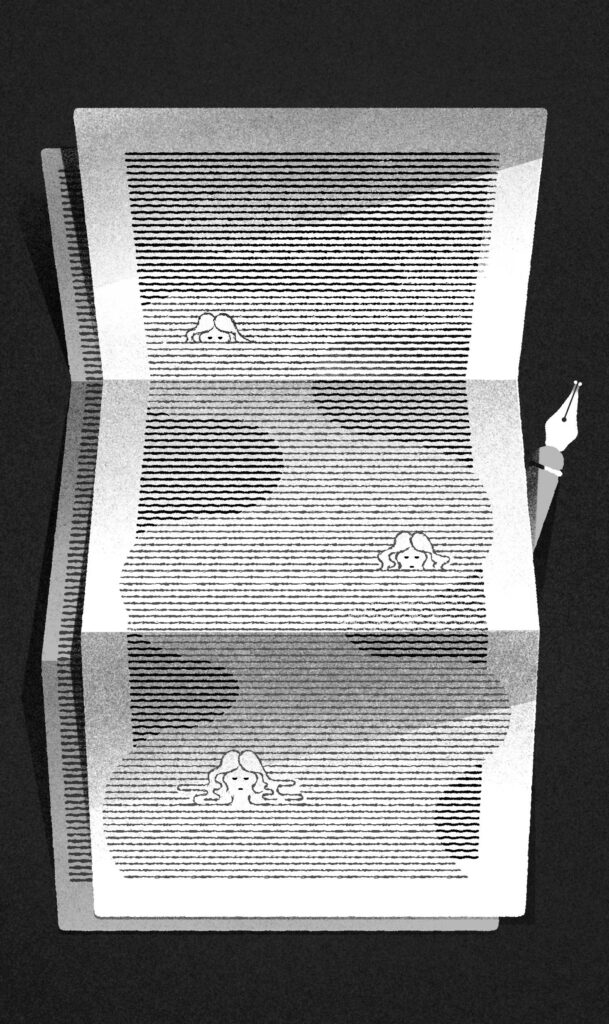

All that a family archive can reveal.

Karsten Petrat

Antoine had his own life-changing tragedy, which happened when the Empress of Ireland ocean liner sank in the St. Lawrence in May 1914. When a Norwegian collier, the Storstad, crashed into its side in heavy fog, opening the hull to thousands of gallons of water, it took only fourteen minutes for the ship to sink. It was a major catastrophe that was quickly overshadowed by the start of the First World War. Antoine’s parents were among the 1,012 people who drowned. Their four-year-old, one of only five children to survive, was forever haunted by the memory of his father’s face as he reached for his son before being swept away by a wave.

From the panic of the crash to the terrifying rapidity of its sinking, Dorion writes particularly well about the Empress of Ireland. Deftly she sketches in the young Corrigan family — Arthur, Emma, and their boy, then called Anthony — who were on their way back to England to finalize their immigration papers. The corpses recovered from the St. Lawrence were laid out in a shed on the Rimouski wharf, and a reporter described the still horror of the scene. “They had been removed from the water like a school of fish,” Hanna concludes from reading a newspaper clipping about the event, “then set out like slabs of flesh, logs now floating on an anonymous earth, confined to the silence they endured before dying.”

Although Hanna is the centre of the novel, Dorion enlarges her beautifully rendered protagonist through multiple points of view. (For the most part, Jonathan Kaplansky’s translation is fluent and tactful, though with occasional baffling awkwardnesses.) Images such as fog, swimming, and the colour blue recur, as well as resonant places, especially the shifting depths of the St. Lawrence River. Problems including alcoholism, sexual incompatibility, and inherited sorrow resurface across three generations. Two adopted characters wrestle with the feeling that they do not fully belong to their parents. And through it all runs the question: Can art save us or at least lessen the pain when our primary relationships are unfulfilled?

The only person we encounter outside Hanna’s and Antoine’s families is Hanna’s best friend, Juliette. Since meeting as children, the two girls have travelled on parallel tracks, with one becoming an artist and the other a writer. In my notes, I wrote, “What is Juliette’s role in the book?” The surprising and satisfying answer is revealed on the last page.

As Hanna nears the end of her search for information about her mother, she and Juliette journey together down the St. Lawrence to Simone’s hometown, Kamouraska. Simone refused to return with her daughter during the final days of her illness, but the friends make a pilgrimage there and to the brick house in Quebec City where Hanna grew up.

Once Hanna knows more about Simone’s story, she feels that she finally belongs to her mother. “This emptiness I never was able to touch, never able to name, I see the source,” she says to Juliette, as they drive back toward Montreal; “it goes back to a river of generations from my mother to my grandmother, and perhaps further still, the fear and sorrow of loss have entered me and begun to flow like blood from another body, from another heart connected to mine.”

Paradoxically, although this is a river of sorrow, recognizing it liberates Hanna. She understands that nothing can prevent us from loving, or from dying. She thinks, “We unravel, we repair what we can.” She will also come to understand that “writing does not repair rifts, it only opens the paths needed for us to reconcile with them.” Leaving her childhood house, where grief and silence had been contagious, Hanna closes her eyes. Instead of the red facade, she sees a blue ocean. Slowly and for the first time, she “rises to the surface of her life.”

The revelations in Not Even the Sound of a River are precisely calibrated but always organic. As the sky brightens and birds fly overhead, Hanna returns to her car. There she opens the last of her mother’s boxes and takes out a sealed letter from Antoine. Simone was never able to bear opening it, but it is the last piece of the puzzle. Carefully, Hanna breaks the seal and begins to read.

Katherine Ashenburg is a novelist in Toronto. Her latest, Margaret’s New Look, is out soon.