In the elegant -former palace of the Duke of Urbino in the hilly, green Italian province of Le Marche, the painting La Città ideale hangs on the wall of one of the second-floor rooms. The long rectangular painting displays “The Ideal City” like a stage set. A grand circular temple-like structure sits dead centre in the painting, facing a public square that we, the viewers, seem to be on the far side of. On either side of that temple, colonnaded square buildings, which manage to combine regularity with variety, line the streets that disappear toward the rear of the canvas.

The painting evokes serenity and order with its simple lines, elegant forms and muted colours. It is also completely devoid of people, sending an enigmatic message that makes it the Mona Lisa of city-landscape paintings. Does it celebrate the architecture and the pleasing geometrical arrangement of space that make a city beautiful? Or is it a sly comment, implying that a city can only be ideal without the messiness of real people intruding? Either is plausible for the Renaissance artist who painted it—either Piero della Francesca or Luciano Laurana—living as he did in a culture and epoch that searched energetically for the principles of good city design and of civic life.

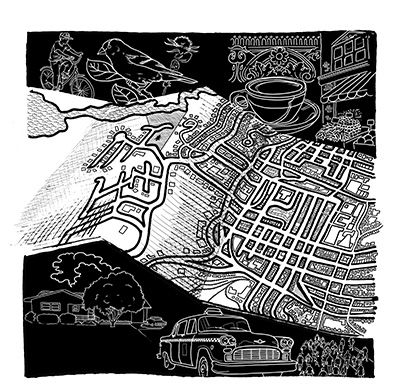

A similar enigma is at the heart of all books about urban design and planning, which have to grapple with two very different perspectives of the city. One is from the air, the bird’s-eye view that strips out the distracting activities of the people-ants moving around in it so that the observer can see the bones of the city: the pattern of buildings, open spaces, street networks. La Città ideale as a work of abstract art.

Greenberg’s book is the story of a life spent trying to design cities so that humans want to live in them.

John Fraser

The other is from the street. There, the city as an entity disappears and becomes instead the backdrop for the lives of real people who walk and drive around in it, shop, eat lunch in the park, gather for protests, buy houses or apartments, and only occasionally stop to admire its buildings and spaces. Even though cities now house more than half of the world’s inhabitants, people who live in them cannot see the overall designs that shape their daily lives. Writing about city building from both perspectives, then, is like being a surgeon writing about how to perform a complex operation while describing what it is like to be a blood cell in an artery in that body.

The picture on the cover of Ken Greenberg’s book, Walking Home: The Life and Lessons of a City Builder, shows a classic bird’s-eye view of The Ideal City. In this case, it is a computer rendering of the future Lower Don Lands in Toronto, a plan that Greenberg played a major part in developing. In spite of that, Greenberg writes from the point of view of someone who has designed cities (or at least pieces of them) from the street-level perspective.

Greenberg’s opening paragraphs bring us down to that level. “Think of Broadway as it follows New York City’s progress from the tip of Lower Manhattan up the Hudson River or Yonge Street running north, bisecting the heart of Toronto,” he begins, inviting readers to walk with him from the centre of any large city to its outskirts. In his imaginary trip, the downtown is lively and welcoming, filled with shops and activity. At the end of the walk, somewhere beyond the city limits, the landscape has become menacing. “As we trudge on through this hostile territory at the side of the road, we see that human activity has withdrawn from the street.”

Greenberg’s book is the story of a life spent trying to design cities so that humans want to live in them, not just designing cities that look good in an aerial drawing. He takes us briefly through his efforts to do that in Toronto—where he was hired to help build the city’s then-new urban design program in the late 1970s—and in some of the many cities where he has worked as a consultant, most of them after leaving his job with the City of Toronto in 1987, including Prince Albert, St. Paul, Boston (where he was interim chief planner for two years), Detroit, Brooklyn, Mississauga, Ottawa, Amsterdam, Washington and Caracas.

For those who do not know, Greenberg is a major star in the Canadian urbanist world, someone whose ability to create thoughtful designs and get warring parties to agree to pragmatic solutions generates respect among the planners and designers I know. (He is also someone I call when I am reporting on topics like how to create suburban downtowns or how to create mixed-use communities around transit.) This book also has forays into Greenberg’s own life story, the history of modernist urban planning, the political backdrop required for good city building, the legislation governing Canadian cities, the impact of gentrification, street design and much, much more—perhaps too much.

Greenberg’s book is the least interesting when he simply repeats the current mantras of urban design. As someone who has read more city–planner reports than I care to think about in my 15 years writing about development in the city and region of Vancouver, I would prefer not to hear about the necessity for “multimodal street design,” “incremental qualitative improvement of public spaces,” “varied building envelopes” and “walkable, mixed-use, transit-oriented neighbourhoods” ever again. Not only is the language difficult and abstract, but it also does not explain anything about how and where people like Greenberg turn these concepts into realities or what those realities feel like to average people.

The book also slows when it repeats the orthodoxies recycled in so many recent city-centric books about how the world developed. To wit: Cities used to be wonderful organic creations. Modernist planning between the 1920s and the 1960s ruined them. Evil governments allowed the car to run rampant. The suburbs are horrible, life-draining blights on the earth. Urbanist Jane Jacobs, who championed inner cities, is a goddess. Thanks to her, we are re-creating urbanism, new and improved. Copenhagen is cool. Yup, been there, heard that. Witold Rybczynski’s latest book, Makeshift Metropolis, does a more nuanced job of explaining Jacobs’s work, including her inability to grapple with the public’s preference for the suburbs. Edward Glaeser’s Triumph of the City provides more original research on the environmental and economic benefits of urban density.

Instead, Greenberg is at his most interesting when he gets beyond the clichés into new territory. Some of the new territory is simply his own life story: Growing up in Brooklyn. Participating in the 1968 revolutions at Columbia University, where graduate architecture students like him had their own specialist take (who knew?) on what was wrong with the establishment. He was part of a group that occupied the school’s architecture building where the protestors targeted the university’s gym being “shoehorned into a Harlem park”—“high-handed action our profession was widely guilty of.” And, beyond university, fighting with (and sometimes losing to) stodgy politicians and bureaucrats who were not prepared to try anything new with their cities.

Another bit of original work is his dissection of the national differences among urban-planning efforts throughout history. Faced with the squalor and confusion of cities as their populations exploded in neighbourhoods unchanged since medieval times, London’s elites chose largely to flee to the country in the 1800s while those in Paris chose to stay and remake the city, hiring Haussmann to create a new urban model. In the modernist era, he notes, France’s Le Corbusier chose to escape the messy metropolis by going up into towers, Britain’s Ebenezer Howard by creating self-contained garden cities, and America’s Frank Lloyd Wright through cities spread out over the countryside, where each family would have a one-acre plot.

But the most informative parts are Greenberg’s detailed descriptions of the elements needed to successfully remake a street, a neighbourhood or a city. He does not do it often, preferring to talk in generalities or to emphasize the need to collaborate with various partners in the system. But occasionally he gets right down to the ground level, like when he describes how Toronto created more pedestrian-friendly streets using protective trees, streetlights geared to walkers and not cars, and paving material in the crosswalks that made them feel like sidewalk extensions. Or how Boston reconnected itself to its waterways, right down to descriptions of the storage spot created for canoes and kayaks in the basement of one office building by the Charles River so that employees could use their lunch break to go paddling.

Like many people of his generation who fell in love with central cities, Greenberg is often dismissive of other types of urban settlement. When he writes about how his own childhood shaped his feelings about cities, he says, “I have never forgotten the Brooklyn neighbourhood where I was born. With time, this neighbourhood and many like it have proven to be incredibly resilient.” And his book’s opening walk through the city reinforces the perspective that only the dense, central city is worthwhile. In it, the downtown is a lively, interesting place, where people make eye contact and move around easily. The suburbs are represented by an ugly arterial road with traffic rushing by. Greenberg never walks through the imaginary suburb where the vast majority of Canadians and Americans live, one with cul-de-sacs where they played games as children among their family homes, schools they walked or biked to, and parks or wildernesses they had access to—places that also inspire fond memories and a sense of connectedness.

He may have more to say on the subject of suburbsas he helps redesign Mississauga, one of his latest projects. Perhaps then he can provide more revelations about the much-mystified task of urban design, where people like him have to perform constant Google Earth–like feats of magic, flying high above the city to reorganize it from a distance and swooping down to pick out just the right paving block on the street for the person walking on it.

Frances Bula has covered Vancouver city politics and development for the last thirty years. Her reporting regularly appears in BCBusiness and the Globe and Mail.