Like the rest of Canada, Quebec is experiencing a crise de conscience in relation to Indigenous people. The video of a dying Atikamekw woman named Joyce Echaquan in a Joliette hospital last September raised in harrowing fashion the question of anti-Indigenous racism, in a place that has not been very self-critical in this regard. François Legault’s subsequent denial that systemic racism exists in the province prompted a social media diatribe from a University of Ottawa professor who accused the premier of leading a “white supremacist” government, whose popularity only confirmed the widespread racism of Quebec society. Unhinged though these accusations clearly were, they prompted the Assemblée nationale to adopt a motion condemning the “hateful, discriminatory, and francophobic attacks of which the Québécois nation is the object within Canada.”

The rhetoric of outrage increasingly becomes the default position in this as in so many other issues of public debate. How can we move beyond it into a space at once humbler and more constructive? Since both the issue of racism — or, for that matter, “Quebec bashing”— and the urge to somehow undo it are so dependent on interpretations of the past, the writing of history can play an especially helpful role. In this regard, the publication of Gilles Bibeau’s Les Autochtones: La part effacée du Québec is timely. This is a book about both the province’s treatment of Indigenous peoples and the question of Québécois identity — and, indeed, it argues that the two issues are inseparable.

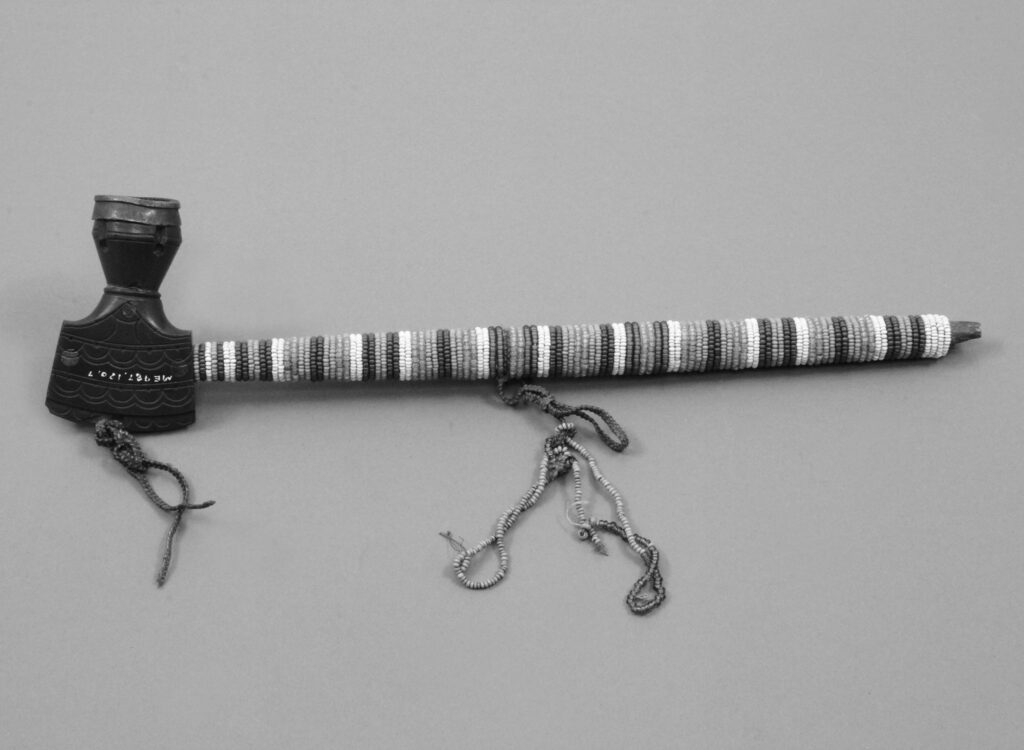

Drawing upon a more complex archive.

Anonymous, Nineteenth Century; McCord Museum

Bibeau, a professor emeritus of anthropology at the Université de Montréal, also holds a doctorate in comparative religion and speaks nine languages. For several years, he lived in Africa and published extensively on differing cultural approaches to illness and healing. His goal with Les Autochtones is to offer an account of the European-Indigenous encounter that is a history à parts égales, or a truly balanced history. This work might be seen in light of the challenge issued by David Hackett Fischer, in the introduction to his magisterial Champlain’s Dream, from 2008. Noting that a few generations ago, historians wrote of European saints and Indian savages, and then in the last generation they began writing of European savages and Indian saints, Fischer urged the current generation of historians to resist the siren call of “ideological rage” in order to “go beyond that calculus of saints and savages altogether” and write about both Europeans and Indigenous peoples “with maturity, empathy, and understanding.”

Bibeau’s subtitle makes his sympathies clear enough. He does not gloss over European guilt for the “effacement” of those who were here first, but he is not interested in mere expressions of contrition; rather, his aim is “to correct, in a way that is substantial and radical, the incomplete and biased account we have produced of the beginnings of our common history.”

The radical nature of Bibeau’s ambitious project has more to do with method than with ideology. While a well-intentioned historian like Fischer might be concerned to “understand” and “empathize” with Indigenous points of view, his reliance on written sources precludes genuine entry into them; he must filter them through the European writings, which tell us almost nothing directly about what these people thought, felt, and experienced in their encounters with Europeans. In his quest for a balanced account, Bibeau proposes that oral sources be given equal weight to the written ones. In doing so, he ventures on a different kind of project, one that incorporates ethnohistory, linguistics, anthropology, archeology, comparative religion, and literature. While it might not meet with the approval of many academic historians, the end result does not seem eclectic or lacking in rigour. Rather, it is deeply informative and richly suggestive.

Drawing mainly on his own field work within the Atikamekw nation in Wemotaci, as well as the oral traditions that anthropologists have collected among the Innu people of the Côte‑Nord, Bibeau identifies the principal forms of teaching that were shared among all the Indigenous peoples of northeastern North America who encountered the French explorers: the Huron-Wendat and the Iroquois, as well as the Algonquian-speaking Innu, Mi’kmaq, Anishinaabe, and Atikamekw. To these oral sources, he, in another bold move, adds the more recent publications of Indigenous and Métis literary artists — Naomi Fontaine, An Antane Kapesh, Rita Mestokosho, Joséphine Bacon, Yves Thériault, Robert Lalonde — who, through their mastery of written forms, function as mediators to bring centuries-old traditions into the present. Bibeau’s account of this rich body of poetry, fiction, and memoir brings to mind something the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin once wrote: “But where the danger is, also grows the saving power.” In this case, that’s the healing power of words.

Where does the Indigenous account of history begin? Certainly not with the arrival of Jacques Cartier in 1534. A momentous beginning from one perspective was from the other an episode in a civilizational story already more than 6,000 years old — an episode of some interest and concern, certainly, but no more than that. Its dire implications for a way of life that had developed over millennia were to become fully realized only gradually.

On the European side of the divide, there is all the archival testimony, especially the writings of Cartier and Samuel de Champlain. One episode in Cartier’s account of his travels stands out in particular. In July 1534, on the shores of the Baie de Gaspé and in the presence of several Iroquois, the French erected a huge cross, some thirty feet in height, that was engraved with the fleur-de-lys and the words “Vive le roi de France.” The French then fell to their knees with joined hands, and Cartier pointed to the sky, indicating to the Iroquois the source of their redemption. What might the onlookers have made of this strange ceremony? According to Cartier, after the French returned to their boats, the chief, Donnacona, had himself paddled out in a canoe from which he launched a “great harangue,” accompanied by signs that indicated all the territory surrounding them belonged to him. It seems Donnacona understood clearly, perhaps more clearly than Cartier himself, the real implications of the heady brew of territorial ambition and Christian justification that were to characterize the development of the “New World.”

After Cartier’s initial, inconclusive forays up the St. Lawrence, it was Champlain who laid the foundations of Nouvelle-France. Champlain has taken his share of hits from iconoclastic historians, but Bibeau’s judgment, while balanced, is favourable. Where Cartier erected crosses, Champlain created beautiful and accurate maps; where Cartier threatened with armed force, Champlain relied wherever possible on alliances and dialogue, which he helped make possible through his practice of having young Frenchmen live among the Indigenous people. According to Bibeau, Champlain’s writings manifest an ethnographic curiosity open to otherness, supported by an attitude of basic respect. It is likely due to the outsize influence of this one remarkable man that there is some truth to the claim that Indigenous encounters with the French were less toxic than those with the Spanish or the English.

Nevertheless, Champlain had his blind spots, especially where land was concerned. The partly deliberate ambiguity about colonialist territorial ambitions that marked Champlain’s tenure was to give way over time to an ever more explicit policy of dispossession, infantilization, and attempted assimilation. Bibeau’s unsparing account of this sad history is in line with authoritative Canadian studies, especially those of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, on whose findings he also leans.

When we turn from the primary French sources to the Indigenous oral ones, we find that the question of territory, dramatically enacted in Donnacona’s gestures, is front and centre. Since it was the Innu who figured most prominently at the great tabagie at Tadoussac, in 1603, Bibeau draws especially on their traditions. The gist of their account of the alliance concluded at the tabagie was that, after some hesitation, they gave the French permission to “disembark” (using the Innu word kapak, which might be the origin of the name Quebec). The French “chief” (most likely Champlain) then made a speech, in which he explained their intention to stay in the area and live according to their own customs. This the Innu chiefs “accepted”— an acceptance furthered by an exchange of goods useful to both sides. Their understanding was that the French would live “along the shore of the salt water”; it seems they never imagined that the newcomers would end by dislodging them and taking away all their lands, even in the interior (the nutshimit).

From the beginning, the French were motivated by a mixture of desire for economic gain (the fur trade and the fisheries), imperial ambitions (the formation of colonies), and high-minded idealism (the Christian missions). And Champlain embodied this mixture fully. As for the idealism, Bibeau is not content to repeat the usual ideological commonplaces. One of the virtues of his book is the serious attention he gives to the religious question; he does justice to the complexity of intentions and understandings on both sides of the spiritual divide. Champlain, for instance, was a Protestant who converted to Catholicism; likely because of the bloody spectacle of religious wars in Europe, he embraced a humanist form of Christianity that saw all human beings as “children of God,” possessing therefore an innate dignity, as well as a capacity for conversion. Unlike the Spanish in the Americas, or indeed the Catholic powers in Europe itself, the French during the Champlain era eschewed forced conversion. The Jesuits, in particular, inspired by the example of Matteo Ricci in China, adopted a strategy of “inculturation,” living among the Indigenous peoples, trying to learn their languages and ways, and adjusting Christian teachings to their customs. The voluminous reports they sent back to their superiors in France, collected as the Relations des Jésuites, constitute a rich source of detailed observation about Indigenous life, without parallel in English-speaking North America.

While the Jesuits were often astute ethnographic observers, they usually displayed an ethnocentric blindness when it came to matters of religion. They consistently dismissed the Indigenous shamans as charlatans, their ritual practices as pagan superstitions, and their creation stories as, in the words of Paul Le Jeune, “irrelevant fables.” It seems that even educated Christians, such as Le Jeune or Jean de Brébeuf, refused to make the distinction between literal and symbolic meanings in Indigenous mythology, while being willing to apply the same distinction to their own Biblical stories. In the eyes of the Innu, with whom Le Jeune wintered, this former professor of philosophy and theology was a “man without great spirit.”

Perhaps the most remarkable figure to emerge from the Jesuit-Indigenous encounter of the seventeenth century was the young Iroquois woman Catherine Tekakwitha — or Kateri Tegahouita, Tegahkouita, Tehgakwita, Tekakouita. The alternative renditions of her name are to be found in Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers, which, despite its countercultural excesses, reflects a diligent reading of the relevant sources. Bibeau, referring to a French translation, gives the novel respectful attention as a “scatological fantasy that is at the same time a religious epic of dazzling beauty.” Beauty, certainly, if one recalls, for instance, the incandescent passage that begins with the question “What is a saint?”

The Anglo Jewish Montrealer also dramatized, memorably, the problem of the Québécois identity in its relation to the (mis)treatment of Indigenous peoples. Who are Cohen’s “beautiful losers”? Those represented by Kateri Tekakwitha and the narrator’s wife, Edith, a member of the A—s tribe, who has committed suicide? The Québécois people represented by F., the narrator’s best friend and a Mephistopheles-like figure, who blows up a statue of Queen Victoria in downtown Montreal? Probably both, and by extension all the other “losers” of Canadian history. As F. puts it, “The English did to us what we did to the Indians, and the Americans did to the English what the English did to us. I demanded revenge for everyone.”

Bibeau’s account of the French-Indigenous encounter undermines the prevailing grand narrative of Quebec nationalism in two significant ways. First, it takes away much of the moral high ground of the claim that the Québécois were the victims of British imperial oppression. The prevailing “social imaginary” of Quebec nationalism has identified the Québécois as a colonized people, who were not themselves colonizers. Bibeau acknowledges the degree of truth in the common view that the French fostered a relationship with Indigenous peoples that was somewhat more equal and benign in its consequences than the English equivalent, whether in the rest of Canada or in the United States. But this does not erase the fact that Quebec, in its origins as Nouvelle-France and its later development before and after the Conquest, must be judged a “typically colonialist nation.”

A second important implication of Les Autochtones has to do with the ancestral roots of the Québécois. The prevailing nationalist image has been of a people who are an island of French language and culture struggling not to be drowned by the surrounding Anglo-Saxon sea. Yet there is recent evidence of a major shift in this view, which has fuelled a debate in the op‑ed columns of Le Devoir about the value of américanité. The concept, put forward by the sociologist Gérard Bouchard, calls for a change of focus in discussions of Quebec identity from France to the Americas, to an acknowledgement of the américanité of the Québécois people —

not, of course, as “Americans who happen to speak French” but as a people who, through time, have become uniquely North American. Yet what constitutes this uniqueness, other than the speaking of French, especially now that Quebec has shed its defining Catholicism? Bill 96 in the National Assembly is the latest political recognition that language is indispensable to the expression of culture, but since it alone can’t provide the content of culture, the question remains.

Bibeau’s book offers a compelling contribution to this ongoing self-examination about américanité. When looking to the past for the Québécois identity, we normally encounter the image of the obedient French Catholic habitant, who faithfully farms his strip of the seigneur’s land along the St. Lawrence; but we also encounter that other image, really a counter-image, of the free-spirited coureur de bois, who roams the untamed forest, hunting, sometimes fighting, answering to no one, remarkably like a New World version of a French aristocrat. Those coureurs de bois, who at one time were the majority of young men in early Quebec, interacted regularly with the region’s Indigenous people. It is not known to what extent they fulfilled the dream Champlain enunciated during a visit to the Huron in 1615: “Our young men will marry your daughters, and henceforth we shall be one people.” But despite the understandable absence of precise statistics, Bibeau does not hesitate to speak the great non‑dit : that what some call the souche pure of francophone Quebec is in reality a métissage, both cultural and biological. As he puts it, “It’s true that our French roots define us, but we are also mixed”— he uses the word métissés —“really and symbolically, with the blood of the Indigenous peoples.” This métissage has become the place of a collective repression within the collective consciousness of the Québécois; and, together with the exclusive claim to victimhood, it has stood in the way of a mature and balanced grasp of their relationship to the Indigenous other in their midst.

Such implications for the question of Quebec’s identity seem highly applicable to the rest of Canada. As Beautiful Losers is intent on saying, in its feverishly apocalyptic way, history itself is a vast mechanism for generating victims. A great many of these have found their way to these shores, making us a country of diaspora peoples, the oppressed and dispossessed, who find it especially difficult to recognize themselves as dispossessors in their turn. And as for the phenomenon of métissage, one might think of John Ralston Saul’s assertion, in A Fair Country, that “we are a métis civilization.”

Societal symbolism is a key to collective self-understanding, so grand symbolic gestures can be important, even if they don’t solve everyday problems (access to safe drinking water, for instance). Toward the end of his history à parts égales, now with the whole of Canada in mind, Bibeau argues for officially designating June 21 as a national statutory holiday dedicated to Indigenous people (similar to what’s currently observed in Northwest Territories and Yukon). While writing the book, he was perhaps unaware of plans for Bill C‑5, which would designate September 30 as a National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. And although Bibeau would not dispute the need for a suitable commemoration of the victims of the residential schools, he envisages a day with a rather different emphasis. It would not be limited to federally regulated workplaces, for one thing, and it would not be primarily an occasion of atonement. Rather it would be a celebratory day for all Canadians, “entirely dedicated to the Indigenous peoples, in official recognition of their ancient presence on Turtle Island and . . . their symbolic connection . . . with the great order of the universe.”

There are already, in effect, two different national birthday celebrations that reflect two distinct foundings, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day on June 24 in Quebec and Canada Day on July 1; this new one would recognize the original Indigenous presence in what became this country. Being ahead of the other dates, June 21 would be especially appropriate as the first in a threefold series of summer fêtes. Moreover, it would be truly Canada-wide. The two currently celebrated foundings exist in a tension of duality, neither entirely united nor entirely distanced (even in their festive dates). Such a new observance, at least in symbolic form, might join them as a mediating third.

Bruce K. Ward is the author of Redeeming the Enlightenment: Christianity and the Liberal Virtues.