Will Ferguson’s latest novel, The Finder, is cinematic in its twists and turns. The narrative globe-trots across three continents, threading together stories of far-flung characters linked by a shadowy figure with a knack for tracking down lost items and a reputation for ruthlessness. It’s hard to resist casting a movie adaptation. A mid-career Al Pacino would star in the title role, with Tilda Swinton as Gaddy Rhodes, the prickly Interpol agent obsessed with locating him. Jack Nicholson, in the Chinatown years, could be Thomas Rafferty, a burnt-out travel writer who becomes the Finder’s unwitting prey. And Jessica Chastain, at her most hard-boiled, would play the flinty photojournalist Tamsin Greene — Rafferty’s on-again, off-again lover.

It should come as no surprise that Ferguson studied screenwriting and film in his earlier life. But instead of pursuing a career in cinema, he became a writer. Before 419, his novel about Nigerian Internet scams, won the Giller Prize in 2012, he was best known for his travel memoirs. Travel writing is a natural fit for someone with movies in their DNA.

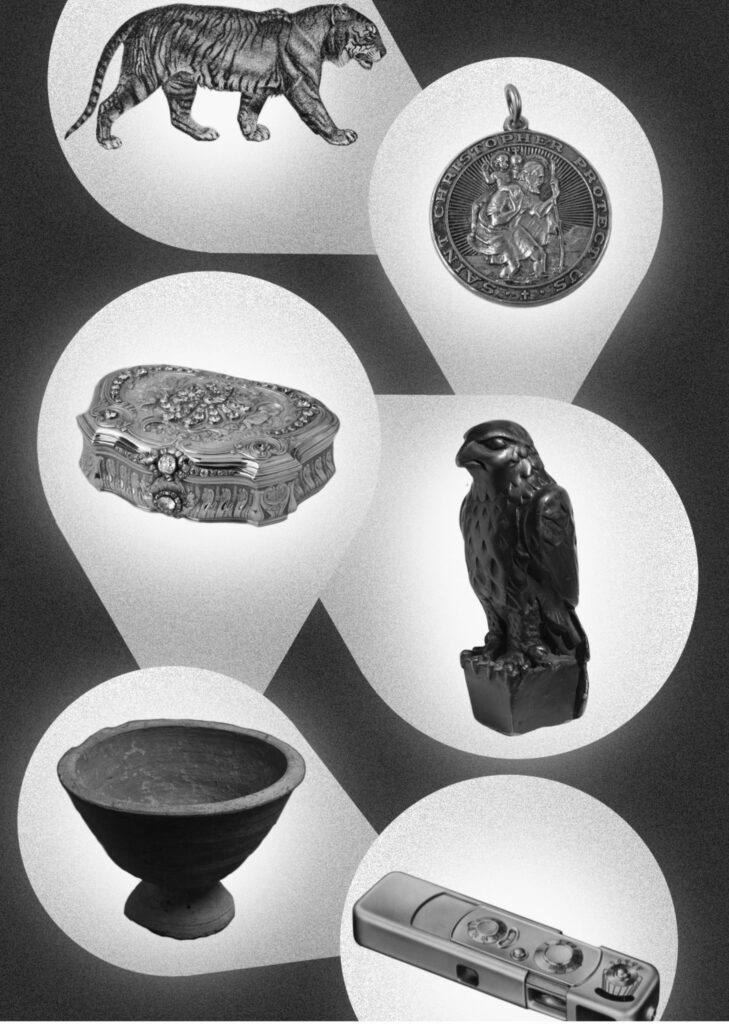

Pay no mind to the MacGuffins.

Brian Morgan

Descriptive passages unspool in The Finder like tracking shots. The story opens on the remote Japanese island of Hateruma, where a policeman’s bicycle “rattled down narrow lanes, past jumble-stacked coral walls. The wisteria was in bloom, faintly aromatic, and they hung over the walls, pink and blue and ripe, like grapes on the vine.” Characters develop in close‑ups: the mysterious central figure has a “faintly feline” face, “the way a fox seems more catlike than canine.” He is a “shadow cast by a shadow,” here one moment and gone the next. Over the course of his various escapades, paths cross and schemes collide as the plot doubles back through intricately woven flashbacks and cutaways. The book begs to be read in a single sitting. I finished it in two. All that was missing was the popcorn.

Despite its title, The Finder is a meditation on loss. Atsushi Shimada, the Japanese police officer whose discovery of a body gets the plot rolling, laments vanished ancestry. Thomas Rafferty’s anguished quest to track down his ex-wife inexorably pulls him into the protagonist’s orbit. Greene, the photographer, craves the adrenalin rush of faraway conflicts — and the moral absolution of a camera placed between herself and the suffering of others. On a sheep farm in New Zealand, where the Finder takes temporary refuge, an erstwhile inventor and his daughter mourn the death of a wife and mother. The Interpol agent Rhodes tracks the elusive protagonist to the ends of the earth to fill the void left by a failed marriage. Ferguson’s point: To be human is to live with loss. We’re all searching for something.

The title character begins life as Billy Moore, the eagle-eyed son of a single mom living on the “dreariest stretch of the dreariest street in the dreariest part of Belfast — and that’s saying a lot.” He earns his moniker in later years, when he proves himself able to locate anything — Buddy Holly’s glasses and Muhammad Ali’s Olympic gold medal are among his reputed finds — and stop at nothing. But the item he covets most, a keepsake medallion from his childhood, is the one thing he can’t recover.

While a novel about loss might not be an obvious choice for a pandemic read, Ferguson’s wit courses through the book. He has a flair for sinewy turns of phrase. Inspector Rhodes is “brittle as a bag of pigeon bones.” A Kiwi wine is “as dry as a mouthful of crackers.” A ramshackle town in the Australian outback “looked like a dresser drawer that had been upturned and picked over, a garage sale at the end of the day when all the good bits are gone.” The dialogue similarly snaps and crackles; tempestuous exchanges between Rafferty and Greene bring to mind the screwball thrust and parry of Tracy and Hepburn.

Ferguson assures readers in his author’s notes that he’s visited all the book’s locations and that his depictions of boozy travel writers and their “squalid existence” are authentic. He recalls penning a budget guidebook to Japan that directed tourists into the ocean. “Anyone looking for parallels between myself and Thomas Rafferty will be richly rewarded,” he says. In case readers haven’t already twigged to it, his notes also indulge his inner cineaste and his kinship with one filmmaker in particular: Alfred Hitchcock. He claims to have hidden “almost a dozen” references within the text. While he divulges a handful, he challenges readers to go back and find the rest —“a treasure hunt, as it were.” The author naturally makes a cameo in the story.

Seen through the rear-view mirror, the nod to Hitchcock bolsters the impact of a scene halfway through the novel. The setting has shifted to New Zealand, where the Finder, wounded by a gunshot, hovers near death in a barn while Catherine, a friendless and misunderstood teenager, secretly tends to him. Their chemistry bears an eerie resemblance to the dodgy relationship between uncle and niece in Shadow of a Doubt. Delirious and oddly confessional, the Finder tries to make Catherine understand who he is and why he chases “objects that are valuable mainly because they were lost.” To better describe his stock-in-trade, he turns to MacGuffins: items that might not have much significance in the grand scheme of things —“a secret code or a diamond tiara. Wasn’t important”— but serve to set events in motion. Then the penny drops: this story is all about MacGuffins. Each character is tethered to one — Rafferty’s fixation on an old love letter, Rhodes’s grief over her long-lost wedding ring. Their yearnings harden into the kind of obsession that formed the grist for classics like Vertigo.

The final scene could have been scripted by the Master of Suspense himself: a pub on the shore of Loch Lomond, in Scotland, “the weather drumming restlessly outside, the amber glow of a fireplace within.” Two men are at a table. One has been poisoned and is dying. The other, remorseless and identified only as “the small man,” opines at length on local history, whisky, ancient saints, Viking treasures, and the fact that, by the way, there are certain people you should never cross. He wipes away drool from the corners of the dying man’s mouth and steps out into the cold rain, realizing, to his own amusement, that he’s lost something: his umbrella. Fade to black.

David Wilson bought his first car, a 1965 Plymouth Valiant, for $75 in 1980.