One evening late in summer 1963, a high school friend took me to visit an older acquaintance of his, already a student at McGill. I don’t really remember either one, but I do have a strong recollection of a small, dark, untidy apartment on University Street — it seemed so sophisticated that I was both intimidated and enchanted — and of the songs coming from the record player: “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “A Hard Rain’s A‑Gonna Fall,” “Masters of War,” “I Shall Be Free.” They were sung by a raw, raspy voice — original, oracular, more angry than sad and making none of the usual effort to seduce or entertain. But what really held my attention was the lyrics, for they expressed ideas and emotions that my fifteen-year-old self was feeling but hadn’t yet articulated.

The voice was, of course, Bob Dylan’s, and this album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, became my obsession. I memorized every word, every note. I bought a harmonica and tried to play along. I spent hours examining the cover photograph as if it might reveal clues to a complex puzzle I was trying to solve. I wanted to be that young man with the wild hair, wearing those jeans and that brown suede jacket, walking down that street in Greenwich Village on that wintry afternoon, with that woman snuggled against my side. Although I understood that the photograph was just another advertising gimmick to help Columbia Records push more product, I bought into its fantasy because I so badly wanted it to be real. Similarly, I accepted Bob Dylan as authentic even though I knew that “Bob Dylan” was the fictional creation of Robert Zimmerman, a middle-class Jewish kid from Hibbing, Minnesota.

Dylan’s genius enabled him to absorb songs and lyrics from a variety of grassroots traditions — Dust Bowl protest, Appalachian bluegrass, Western cowboy, African American spiritual, Dixieland jazz, sea shanties, union anthems — and reinterpret their hardships and sorrows, their fortitude and faith, for a young, modern, bourgeois, secular audience. Nor did he rely on musical talent alone. He was blessed with a fast mind, a piercing wit, and a native intelligence, which he supplemented with self-education in literature, poetry, history, and politics. These assets gave him a vast, subterranean pool of sounds and images into which he could drop his bucket and pull up “Girl from the North Country,” “Chimes of Freedom,” “The Times They Are A‑Changin’,” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.” And that made me follow him, just a ragged clown behind, through the smoke rings of my mind, in the jingle jangle of the morning.

There was much then that I didn’t yet know.

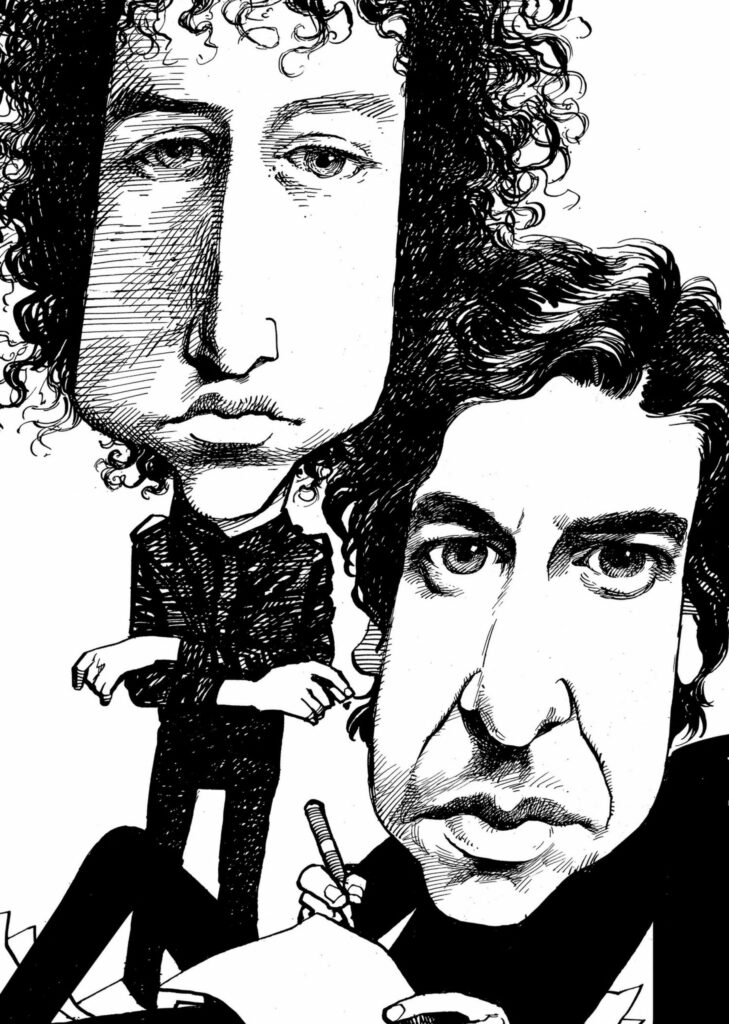

David Parkins

There was a lot of hand-wringing in lecture halls and the media when Dylan won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016. Was his work really literature? But I had no reservations. He had taken his name from the well-known Welsh poet, of whom the hundreds of thousands of boys subsequently named Dylan have probably never heard. He had drawn inspiration from Homer and the Bible, Virgil and Ovid, Provençal troubadours and English balladeers, Rimbaud and Whitman, the French surrealists and the American Beats. Then he had hitched the powerful locomotive of music to the long train of poetry and sped off down the tracks, leaving conventional practitioners waiting on the platform for the next train to tenure or giving readings to each other in a vintage parlour car shunted to a sidetrack in the rail yard.

He stole the limelight from Auden, Frost, Lowell, and the other aging lions of modern poetry, left Pound and Eliot fighting in the captain’s tower on Desolation Row, and reduced poor Allen Ginsberg to the status of groupie, playing finger cymbals in the chorus at the edge of the stage in a pathetic attempt to stay hip and famous.

Ultimately, Bob Dylan gained the kind of celebrity that belonged to Lord Byron when he published the first two cantos of “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,” in 1812, to the point where fans thought Dylan too would die young and, we hoped, for a cause as valiant and romantic as the independence of Greece.

I happened to encounter Dylan up close when, in November 1975, my friend Sarah and I found ourselves seated beside his table in a bar in Quebec City. We had gone to the city to see his Rolling Thunder Revue, which remains the most memorable concert I have ever experienced. I felt overwhelmed, as if I had walked into an alehouse in Elizabethan London and come across Shakespeare drinking with members of his company before an opening at the Globe.

Dylan was true to his reputation: tense, terse, suspicious, and solitary, despite the entourage of Black women and hip musicians too cool or stoned to speak to each other. He sat with his back to them, facing out to the talkative, excited crowd, most of whom were sneaking glances while pretending not to have recognized him. His fearsome stare, which seemed to be a dare but may have been mere introspection, acted like a spell that kept everyone from crossing the empty space in front of him, like the hypnotism by which a matador keeps a half-tonne bull at bay. His feet pumped rapidly and constantly from nervous energy or to music only he could hear. Joni Mitchell, who had joined the tour for a while, thought him an uncommunicative, cocaine-addled brat. “Is your silence that golden? Are you comfortable in it?” she asked in a song written two years later. “Are you really exclusive or just miserly?”

I saw Dylan differently after this encounter. I was literally disillusioned. However much I loved Blood on the Tracks and Desire, I now saw Dylan to be what he always claimed he was: a performer, not a prophet. Beneath the false idol that I had set on an altar in my mind, there was just another song-and-dance man, dragging his battered body from town to town, night after night, on a never-ending tour to promote his latest album, taking off the greasepaint after the show, counting the gate at the end of the day. By his own telling, it wasn’t Shakespeare the creative genius with whom he identified, but Shakespeare the theatre impresario. Was the financing for Hamlet in place? Where to get hold of a human skull?

Bob Dylan, I came to realize, didn’t possess genius so much as he was possessed by it. Like all shamans and oracles, he was a medium through whom the gods spoke, as unconscious of the truths he revealed as he was of the music he summoned forth. “All I’d ever done was sing songs that were dead straight and expressed powerful new realities,” he insisted in his memoirs. “I had very little in common with and knew even less about a generation that I was supposed to be the voice of.” No longer expecting him to mean anything more, I wasn’t disheartened later to see photographs of him playing golf in Las Vegas or hear him croaking Frank Sinatra standards or learn that he had become, for a while, an evangelical Christian.

The larger realization was that the great gift bestowed upon him at birth had been a curse rather than a blessing. It certainly hadn’t made him wise or happy or even nice. I mean, who would want to be Bob Dylan? What a living hell to be a mere mortal trapped inside the statue of a golden calf before which millions prostrated themselves and prayed for some kind of healing. How asphyxiating. How infuriating. No wonder he sounded so angry, so desperate, in outbursts such as “Ballad of a Thin Man” and “Idiot Wind.” No wonder he compared himself to Homer’s Ulysses, condemned to wander, drugs dropped into his wine, the wrong woman in his bed, spellbound by magical voices, come so far and blown so far back by an ill wind that blows no good.

Dylan came to my attention too late for me to have seen him perform in Montreal in summer 1962, only four months after his obscure debut album, when he played to sparse audiences in a couple of small clubs. So I hastened to nab a good seat for his concert on February 20, 1966, at Place des Arts, the new, 3,000-seat auditorium built primarily to showcase symphony, opera, and ballet. However inappropriate the hall’s elegant decor and plush seats, the superb quality of its sound allowed close listening, particularly during the first half when Dylan performed alone, with just his acoustic guitar and harmonica as accompaniment. After the intermission, he returned with the Hawks, a five-man group of rockabilly musicians out of Toronto who later gained fame in their own right as the Band. Unlike the negative reactions he encountered elsewhere on that tour, there was a perceptible thrill when he picked up his electric guitar and launched into powerful versions of “Positively 4th Street,” “Leopard-Skin Pill‑Box Hat,” and “Like a Rolling Stone.”

By chance I was in the same row as two prominent Montreal poets, the bombastic Irving Layton and his protégé Leonard Cohen. Even to speak of “prominent poets” is to highlight a difference between then and now. However marginal, poetry was still alive in the early 1960s. Robert Frost read at Kennedy’s inauguration. Yevgeny Yevtushenko was on the cover of Time. Lawrence Ferlinghetti and the other Beats were household names. Sylvia Plath’s death made the news. Enthusiasts, young and old, turned out in large numbers for public readings in university auditoriums and coffeehouses. Poets were given respect, and whether or not their work was any good, it often acted as a love potion. In 1965, the National Film Board of Canada considered Leonard Cohen important enough to be the subject of a forty-five-minute documentary, based on little more than the thirty-year-old’s four slim volumes of verse and his exceptional charm. Long before Cohen attracted an international following, he was that most enviable of men, a local hero.

Ladies and Gentlemen, Leonard Cohen, a black and white exercise in early cinéma-vérité, made a deep impression on me, and Cohen began to weave in and out of my life until his death in 2016. I was seduced by the archetypal portrait of a poet’s life: scribbling lines in a squalid room while smoking an Old Port cigar, partying with his demimonde friends, reading his work to rapturous audiences, hobnobbing with the literati, wandering the midnight streets of Montreal alone in search of inspiration while his muse, a Norwegian blond, awaited him in Greece. Here was a poet, maybe even a great poet, who wasn’t dead or old or brushed by the wing of madness. Here he was in my city, drinking in Le Bistro, eating a smoked meat sandwich at Ben’s, walking past the burlesque houses on the Main. While I struggled over an essay or crammed for an exam in the McGill library, I used to see him stroll in and leave an hour or so later, invariably with a pretty woman at his side.

Like me, though thirteen years older and Jewish, Cohen had grown up in the wealthy Anglo-Quebec neighbourhood of Westmount, played in Murray Park, joined a fraternity at McGill, and known the pressure to study law or enter the family business. “I don’t like the way the evidence is building up,” he teased the off-camera interviewer in the NFB film. “I’ve got Westmount, I’ve got the chauffeur, I’ve got the fraternity, I’ve got the politics. All I have to tell you now is that I was good in sports, and I’ve completely ruined the cliché of the poet forever.”

There existed and may still exist in Canada a presumption that no one of Cohen’s background could be a genuine artist. He lacked, as he said of his first encounter with Allen Ginsberg in New York in 1957, “the right credentials to be at the centre table in those bohemian cafés.” Moreover, in a community as provincial and practical as postwar English Montreal, the desire of a privileged young man to be a poet, a painter, a novelist, an actor, or a composer was viewed as a phase at best, a pretension at worst.

I too suspected something phony about Cohen or, at least, about his image, something of the poseur, the pseud, the false lover: “The world was being hoaxed by a disciplined melancholy,” he hinted in A Favourite Game, his first novel. There were scenes in the documentary in which he pretended to be asleep in his bed or alone on a walk despite the obvious presence of a camera and crew. Even when he scrawled “CAVEAT EMPTOR” on the wall while being filmed taking a bath, it seemed less a subversive message to alert the viewer that Cohen wasn’t “entirely devoid of the con,” as he put it, than yet another trick to charm us with his candour.

My suspicions seemed confirmed when, exiting the Dylan concert in February 1966, I overheard Cohen arguing with Layton that we had just witnessed the future of poetry, that poetry had to get out of the cellar and into the marketplace. He had made the same point a month earlier to F. R. Scott, a founder of modern poetry in Canada and the leading light of the Montreal literary scene for decades. “Dylan’s already making a million dollars a year!” Cohen marvelled, prompting Frank Scott to rush out in the middle of his own party to buy a couple of albums to see what all the fuss was about. After listening to “The Times They Are A‑Changin’,” Scott quipped, “Eight Canadian dollars for an American cliché.” The other older poets in the room were aghast at the caterwauling they heard coming from the record player (or so Scott told me when recounting the event years later), and they recoiled from the notion of sending Calliope, Euterpe, and Erato out into the streets to whore for a living.

In crass terms, Leonard Cohen needed to find a way to make money if he wanted to escape a future in business, law, or teaching. Poetry was never going to pay the rent, and he had begun to suspect that he would never be among the greats, regardless of the early acclaim and the occasional good poem that made “the whole dismal enterprise” worthwhile. Nevertheless, whatever his ulterior motives — whether money, women, or fame — he was right. The traditional forms of poetry were dying and being reborn as popular song.

Barely six months after seeing Dylan at Place des Arts, Cohen headed off to New York, where he succeeded in selling his first songs to Judy Collins, who turned “Suzanne” into a hit. By the end of 1967, he came out with his legendary first album, even though his voice was funereal and his playing was limited to a few chords based on the folk songs he had learned at camp, the cowboy songs he had played with the Buckskin Boys at university, and the basic six chords of flamenco that he had picked up from a Spaniard he happened to meet in a Westmount park.

“To address people with song was always what I wanted to do,” he once told me. “Things might have been better if I had a job and written in the evenings, but I doubt it. At some point you have to embrace your own destiny.”

Songs of Leonard Cohen became the soundtrack to my last semester at McGill, most fully expressing in words and music my own yearnings for love, freedom, and truth. At the same time, it transformed the familiar into the universal. I knew the place near the river where Suzanne had fed him tea and oranges. I knew the sailors’ chapel in Old Montreal with the statue of the Virgin, her arms raised in blessing, overlooking the harbour.

Though his second and third albums made as deep an impression as the first, I couldn’t shed completely my doubts about Cohen’s authenticity. Perhaps it was another case of a prophet being without honour in his own land but, from certain angles, he appeared manipulative as a seducer, cloying as a romantic, and vain as a spiritual seeker. There was a narcissistic studiousness in the way he constructed his public image, from the dapper suits and signature fedora to the poses in front of a mirror and the self-referencing in his songs. There was his cowboy period in Nashville and his dabbling in Scientology. Worse, there was Death of a Ladies’ Man, the overproduced album that came out in fall 1977.

In spring 1984, Saturday Night commissioned me to review Cohen’s latest collection of poetry, Book of Mercy, which came with an opportunity for a half-hour interview in a Toronto hotel room. I had run into him a few times at various book launches and social events, but this was to be our first and last serious conversation. Unfortunately, I happened not to care for the poems, fifty formal supplications to God in the archaic style of Biblical rhetoric. They struck me as literary exercises or private prayers, and even when I accepted the elegance and sincerity with which they had been written, I felt there was something untoward about the poet wearing his sacred heart so conspicuously upon his sleeve in order to fulfill a contract with his publisher.

To make matters worse, I was fighting a particularly severe flu and had to drag myself from two days in my sickbed, pale, weak, still feverish and shivery, with rheumy eyes and nasal congestion. I felt nervous and thick-headed, but Cohen could not have been more gracious or sympathetic. Did I want a cup of tea? Did I want a glass of water? Did I want a box of Kleenex? With his precise, almost ceremonial courtliness, his dark suit and tie, his famous voice speaking in a slow, quiet, solicitous tone, he behaved more like an obsequious valet than an international celebrity.

He answered my questions, even the barbed ones, with the same care and formality, as though he had never heard any so original or insightful, and he disarmed me even more by surrendering to my skepticism. While insisting that these psalms had been the only way he could penetrate what he described as “a silence not only of words but also of feelings,” he no longer identified with the emotions that had inspired them. “Now people of a more constant religiosity approach me in a way I can’t respond to,” he said, “because that isn’t my natural mode. Disloyalty develops toward the book in my personal behaviour, and it becomes just an object that can be sold.”

As if to demonstrate that disloyalty, he turned his attention to the housekeeper who had come to tidy his room while we were talking. “Did you see her? Did you see how beautiful she was? Did you see her uniform?” Then there came the impish smile, the bad-boy laugh. “Yeah, I guess I’m still in the same mess. But there’s a certain perspective on the mess now, some kind of light on the matter.”

After the tea and sympathy, I felt like a traitor with my negative review — especially when an editor subtitled it “What happened to his talent?” But the old doubts had resurfaced. Hadn’t Cohen undercut his own book in the interview, or had that been just a false modesty by which he appeared to be giving a journalist the straight goods? Similarly, though I had basked in the warmth of his attentiveness, there was an exaggerated, passive-aggressive unnaturalness to his good manners, as if, by making my needs his first priority, he had been trying to hide or repress a darker, chillier, truer self. Replaying the tape, I realized how rehearsed and honed by repetition had been the answers that I thought so intimate and intended only for me. The secret of hypnosis, they say, is that the subject wants to be placed in a trance, and Cohen learned at a very young age how to use the gravity and pace of his voice to get his family’s housemaid to take off her clothes.

There was much then that I didn’t yet know or appreciate about him: the periods of paralyzing depression, the hours of laborious thought and craft that he dedicated to every verse and word, the years of rigorous meditation in a cabin on Mount Baldy. No poseur could have sustained that much serious, studious, solitary discipline over so many decades. Indeed, I now would argue, later Cohen produced political anthems with more bite and resonance, including “First We Take Manhattan” and “Everybody Knows,” than later Dylan. And when Cohen was forced reluctantly back on the road in his seventies after being swindled out of his life savings, he capped his reputation with a series of extraordinarily moving, generous, almost shamanistic concerts. It was as if he had finally grown into the image he had wished for himself as a young man.

As for me, tentatively, warily, like an explorer setting out into unknown territory, I followed Leonard Cohen off the mountain. I expanded my walking range from the predominantly English-speaking downtown core along St. Catherine Street to the Jewish delis on St. Laurent Boulevard and onward to the working-class districts of French Montreal, which I had been warned as a boy were too dangerous to enter by day or by night. I heard Gordon Lightfoot and Muddy Waters perform in small coffeehouses, Gilles Vigneault and Monique Leyrac at the Théâtre du Nouveau Monde, and Frank Zappa at his zaniest during a two-week gig at the New Penelope. And though my Anglo background, my stammered French, and my fundamental shyness hindered me from entering more fully into the Quiet Revolution, I embraced the high spirits and creative vibrancy it unleashed. I gave up beer for wine, switched from hamburgers to croque-monsieur, swapped John Stuart Mill for Jean‑Paul Sartre, exchanged Simon & Garfunkel for Jacques Brel and Charles Aznavour, smoked Gitanes, wore turtleneck sweaters, and pretended.

Ron Graham is an award-winning journalist and the author of The Last Act: Pierre Trudeau, the Gang of Eight, and the Fight for Canada.