Anyone who goes to Jasper National Park can gaze up at a 3,300-metre peak called Mount Edith Cavell, named in 1916 after a British nurse who was executed by the Germans for helping Allied soldiers escape from Belgium. Cavell never set foot in Alberta, let alone saw the mountain that now bears her name, but the memorialization reminds park visitors of both her bravery and the colonial connections between Canada and Britain, fondly referred to as the “old country” by many of the women who worked alongside her.

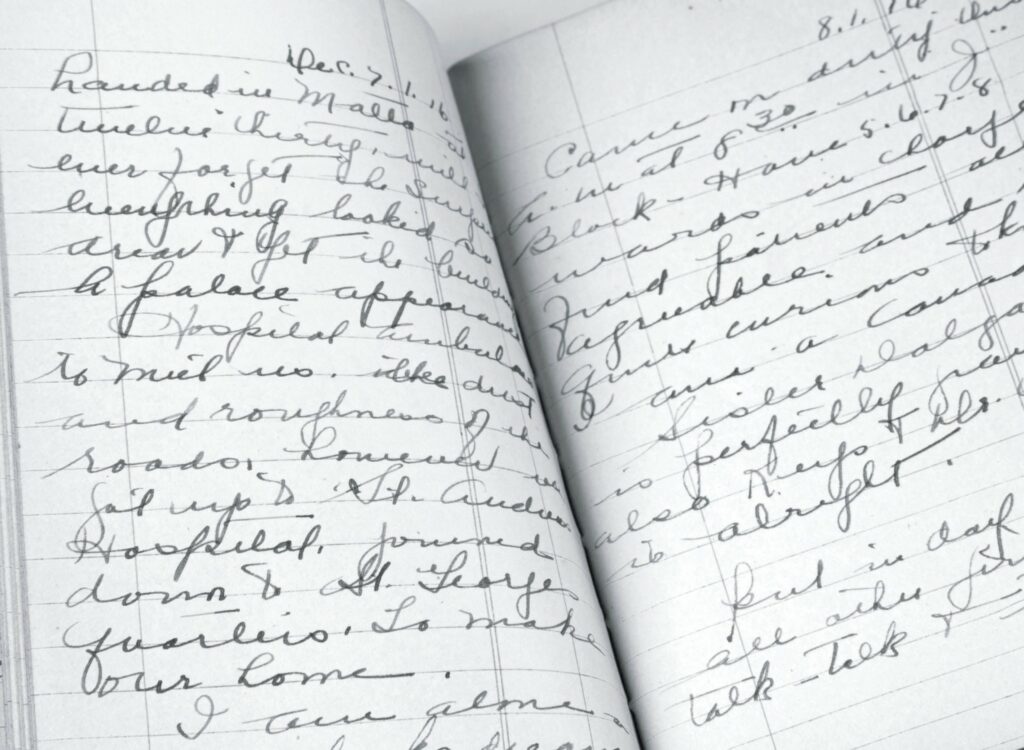

Ross Hebb turns to one such woman in A Canadian Nurse in the Great War. The pages of Ruth Loggie’s diaries “grant us a unique peek into a little-known moment of our history,” the Maritime historian writes. “While 420,000 men served overseas during the Great War, only 2,100 Canadian women served as army nurses.” Hebb details the relative silence of these women in the postwar period, when researchers started requesting information about the experiences of non-combatants. Reintegrating into Canadian life — settling down and finding employment — often took priority over talking about the recent past.

Those who had enrolled with the Canadian Army Medical Corps continued to receive little recognition as subsequent studies focused on battles and bravery, not women and wounds. As a result, there’s much we still do not know. “How did they cope? What were their thoughts as they lived through what they knew were world-altering events?” Hebb asks, before noting that Loggie “was but one nurse of hundreds in the CAMC, working in one of many Canadian hospitals in France as part of the Canadian contribution to the British Empire’s war effort.”

The accrual of mundane details can reveal a depth of emotion.

Luella Blanche Lee Fonds; Library and Archives Canada; Flickr

Hebb follows Loggie’s trajectory as a wartime nurse, beginning with her training at the Montreal General Hospital, which she completed in 1910. Originally from the small fishing village of Burnt Church, New Brunswick, she applied to the corps five years later, in 1915, serving in a unit formed by McGill University. The book includes a photograph of Loggie in her late twenties, “enjoying a relaxed moment” in Boulogne, France. The photographer was Clare Gass, her best friend, whose own journals help Hebb decipher the gaps in his primary text. When the diary ends abruptly on November 23, 1916, for example, he turns to Gass: “Given the extraordinary extent of parallel entries concerning each other, one would think that Clare’s diary would contain an explanation as to why Ruth’s diary ends as it does. Sadly, this is not the case.” Because of parallel gaps, he concludes something big must have affected them both, most likely a large number of admissions following the Battle of the Somme or increased illness among the hospital staff.

Hebb leaves Loggie’s diaries unedited, which is a generous and refreshing approach that allows the accrual of mundane details to reveal a depth of emotion that would be difficult to capture otherwise. On May 14, 1915, while crossing the Atlantic, Loggie wrote that “five torpedo boat destroyers quietly appeared from nowhere.” The next day, upon arriving in Plymouth, she commented on the Lusitania ’s sinking, which had occurred a week prior: “Terrible news of the Lusitania and we heard report that a report had reached here that we were torpedoed.” The real-time confusion — between what was happening and what was being communicated at any given moment — is haunting and memorable.

Hebb does add spare interjections to help situate key events and locations, such as Boulogne, “a place which is to figure prominently in the McGill Unit’s future.” He also notes “No entries” when Loggie was not writing, whereas many editors of letters and diaries skip past dates with no corresponding entries. By emphasizing the lacunae, he draws attention to archival silence, which can speak volumes.

Complete with Hebb’s precise commentary, A Canadian Nurse in the Great War is a valuable contribution to the literature of the First World War generally and women’s accounts of it specifically. This also is the type of book that makes one thankful for the small and independent publishers across the country that are helping to promote herstories and the experiences of marginalized people. And where else could a historian suggest that “tramping”— one of the many lively verbs used by Loggie — is a particularly New Brunswick idiom?

Martha Hanna’s Anxious Days and Tearful Nights shares a starting point with Loggie’s journals, in this case with a soldier boarding the Megantic from Montreal to Liverpool, a week after the sinking of the Lusitania. Writing in the present tense, Hanna imagines his departure:

Montreal. 14 May 1915. The Megantic is about to set sail for Liverpool, the men aboard bound for war. Ted Clarke is in a hurry. Before the ship weighs anchor, he needs to send his wife and children a postcard. Much to his regret, he had not been able to say goodbye in person when the troop train pulled out of the Oshawa station for Montreal.

A paragraph later, Hanna tells us that no trace of further correspondence remains.

Hanna, a history professor at the University of Colorado, in Boulder, creates arresting immediacy throughout her book, bringing anecdotes to life to demonstrate the psychological impact the First World War had on everyday lives. Frances Clarke was thirty years old, with five children, when she arrived from England in 1914, bound for southern Ontario. Saying goodbye to her husband just a year later was the type of experience some 90,000 other women shared.

Several tropes have prevented a full acknowledgement of the war’s impact on those left behind, Hanna argues, including the dominant soldier-as-bachelor narrative. Citing statistics from conscription, enlistment, and service records, she notes that married men actually formed a large part of the Canadian army — much larger than previously recognized — and that such research is essential for understanding the spouses who remained at home.

Hanna’s coupling of in-depth archival research and first-person correspondence brings to life the “anxious days and tearful nights” that lasted throughout the war. She draws upon the recurring communication between Laurie Rogers and his wife, May, for example. Before enlisting at Sweetsburg, Quebec, in February 1915, Laurie spent weeks arranging for his absence from the Eastern Townships. While away, he wrote May with guidance and advice, reminding her to collect wood for the winter and to clean the manure out of the barn, and suggesting she hire a medically unfit soldier returning from England as a farmhand. Though married, May had to confront the many “challenges of life as a ‘single’ woman in a small farming community,” Hanna writes. “The hired hand was obstreperous, a neighbour refused to pay his debts, the hen killed the ducklings, and the cats ate the chickens.”

Facing wartime turmoil to the point of destitution, some sought help from the Manitoba Patriotic Fund for supplemental support to feed the children. Hanna quotes an unnamed source who expressed gratitude for the emergency fund: “I want to thank you for your kindness to me. I am sorry I had to ask for it but as I could not see anything else to do. With it I am getting a pair of shoes for myself and paying a couple of small bills. Thanking you again for your kindness.” Even now, more than a century later, it is humbling to read of such sincere gratitude expressed toward a provincial institution.

Returning to the “old country” or heading there for the first time to stay closer to their spouses was a last resort for others. Alice Leighton, from Ontario, was one of many war wives who relocated to England, without knowing anyone there except her husband. She stayed at the posh Cecil Hotel and was able to experience the sights and sounds of London, but Hanna points out that Leighton’s experience as a “bedazzled tourist” was far from common.

Betty Mayse of Brandon, Manitoba, was “on the edge of a nervous breakdown” in April 1917, when she hadn’t heard from her husband, Will, who had been training for the “big show” at Vimy. While waiting for any news of him after the battle, reports of which filled the dailies, she went on a cleaning frenzy — painting the ceiling and stuffing the cracks — only to hear eventually that Will was quarantined on the other side of the Channel. He hadn’t made it to Arras, France, at all. “I don’t think I knew how much I had been pushing it, till your letter came,” Betty wrote him. “I nearly had a fit between the letter and the kids.”

Like Hebb’s A Canadian Nurse in the Great War, Hanna’s Anxious Days and Tearful Nights vividly captures the impact of a defining conflict on women who embarked on emotional and physical journeys, both at home and abroad. Few of them have mountains named in their honour, but as these two books show, their experiences and first-hand accounts make for an increasingly nuanced view of the First World War.

Shazia Hafiz Ramji is the author of the poetry collection Port of Being. She divides her time between Toronto and London, where she’s writing a novel.