Thinking back on the summer of 1929, when he was hanging out with the expatriate literary community in Paris, the novelist Morley Callaghan recalled how Ernest Hemingway’s lonely expression would change to a “quick sweet smile” whenever he entered a bar and saw friends. After their time together ended, Callaghan continued to follow reports of Hemingway’s life and watched as he became both a successful writer and a global celebrity.

In July 1961, Callaghan received a call from an acquaintance who worked for one of the wire services: Hemingway had died. Callaghan couldn’t believe it. “Don’t worry,” he said, “he’ll turn up again.” This response wasn’t as strange as it might seem. Several years earlier, in 1954, Hemingway’s death had been widely reported after a plane crash in Africa, yet he had emerged alive. The man on the phone assured Callaghan that this time, Papa really had died. To Callaghan, the news felt as though “the Empire State Building had fallen down.”

Ernest Hemingway left all of his property —“real, personal, literary or mixed”— to his fourth wife, Mary Welsh Hemingway, the subject of an in-depth and finely researched book by Timothy Christian. With Hemingway’s Widow, the first full-length biography of Mary, Christian reveals a fascinating woman, both for the part she played in Ernest’s life and in her own right as a pioneering journalist and war correspondent.

It was Lord Beaverbrook, the publishing magnate, who provided Mary Welsh with her first big break by bringing her onto the staff of London’s Daily Express, in 1937. Welsh had reporting experience from her time at the Chicago Daily News (where she had worked with Ernest’s younger brother, Leicester). But, like most other female journalists of the time, she had been relegated to covering society events. With Beaverbrook’s paper, she could do real news, beginning with an article on her first day about the disappearance of the aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart.

Together they found that rare thing.

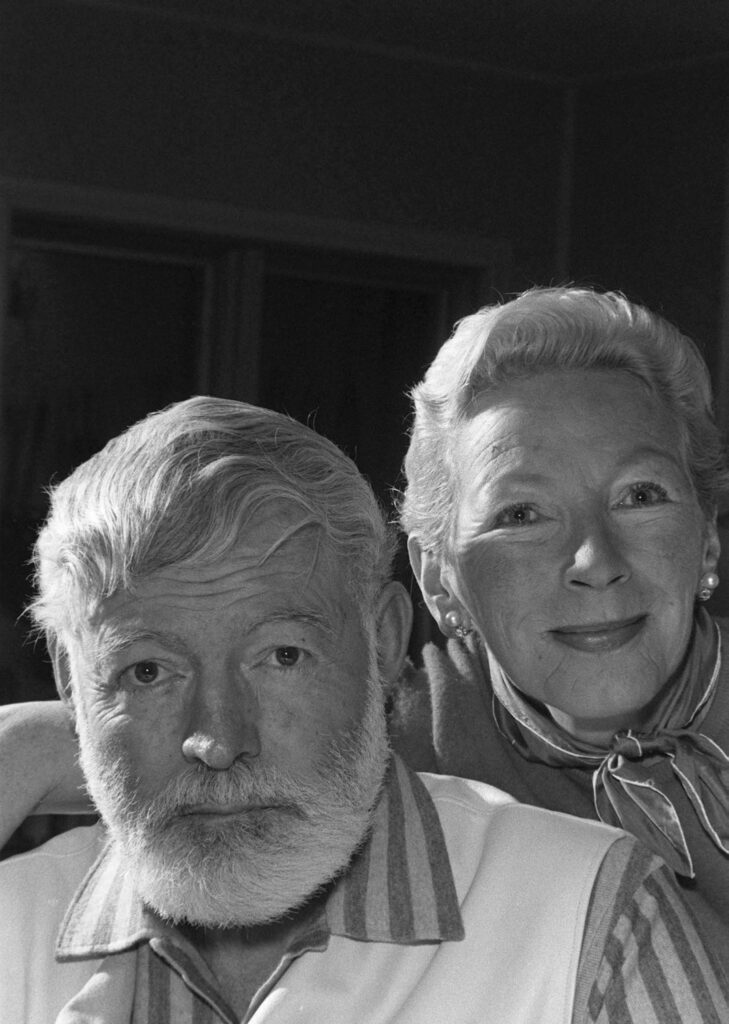

John Bryson, 1959; Getty Images

Welsh embraced the challenge of writing about world events, and she soon had major assignments, including an interview with the United States ambassador to London, Joseph Kennedy, a few months after Britain declared war against Germany. During the Second World War, she was accredited as a journalist with both the Royal Air Force (for the Daily Express) and the U.S. Army (for Time and Life). “Her identity card showed she was five feet three inches tall, weighed one hundred twenty pounds, and enjoyed the rank of captain,” Christian writes.

Welsh met Hemingway, also a war correspondent, in London in 1944. For him, the infatuation was immediate, and he proposed on an early date, when they were both still married. Although her current relationship appeared to be foundering, she was not sure Hemingway was the right man for her, especially since — as Christian attentively details — he could become verbally and physically violent when inebriated. But with poems and letters written while reporting on battles in France, Hemingway wooed Welsh and ultimately won her over.

During their time together — over a decade and a half — Ernest did some of his best work, assisted by Mary’s suggestions and support. In 1953, he won the Pulitzer Prize for The Old Man and the Sea, and the following year, the Nobel Prize. He also composed a memoir of Paris life, later edited and posthumously published by Mary as A Moveable Feast.

That same period, however, also included some of the author’s most devastating personal struggles. By early 1961, Hemingway’s immense talent was deteriorating alongside his physical and mental health. He was still just sixty-one years old, but when he attempted a tribute for John F. Kennedy, in honour of his inauguration as president, it took a week for him to draft a few sentences. “What does a man care about?” the anguished author asked a close friend. “Staying healthy. Working good. Eating and drinking with his friends. Enjoying himself in bed. I haven’t any of them.” On the morning of July 2, he shot himself.

Drawing on extensive research, Christian paints a portrait of a married couple who, whatever their difficulties, ultimately found in each other a rare thing: intimate understanding. With his background as a law professor, including at the University of Alberta, Christian carefully presents his evidence, especially in a compelling analysis of how Mary handled her role as the preserver of Ernest’s legacy.

By examining her letters and diary — and by comparing the published version of her autobiography, How It Was, with an earlier draft — Christian details numerous inconsistencies and, sometimes, lies. He also considers Mary’s version of events against those of living witnesses, including Valerie Hemingway (Ernest’s former assistant and, later, daughter-in-law) and Patrick Hemingway (Ernest’s son). While Christian properly criticizes Mary for some aspects of how she managed her late husband’s estate, especially with respect to his children, he also shows that, in key respects, Ernest’s trust in her was ultimately justified.

When the Library of Congress tried to convince Mary to leave Ernest’s papers with them, the directors took her down into the depths of the building to see where they stored valuable papers. She knew that her husband had felt most at home outdoors — fishing in Michigan, hunting in Africa, escaping on his boat into marlin-filled seas — and she “hated the idea of Ernest being stuck down in the ground in those dark corridors with so, so, so many other people.” On another occasion, she stood up to the Cuban leader Fidel Castro during a dramatic personal meeting at Finca Vigia. She was then able to return many of Ernest’s most important personal artifacts to the U.S. In the end, she entrusted the precious materials to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

In contrast with a marriage that ended in depression and despair, Mary’s commitment to preserve Ernest’s belongings can be seen as a powerful act of restoration. The stunning cobalt vista of Boston Harbor through the library’s windows evokes feelings of wonder — similar to those the couple would have experienced as they sailed the Gulf Stream together, at their happiest.

So perhaps Morley Callaghan was not wrong when he said on hearing of Hemingway’s death, “Don’t worry, he’ll turn up again.” The decisions Mary made as Ernest’s widow helped ensure his afterlife — in a place he would have loved.

Sharon Hamilton writes about baseball, literature, and Jazz Age cocktails.