Among the many unfortunate aspects of the decline of the mainstream news media in Canada is the disappearance of regular labour coverage. Apart from one or two journalists who cover workplace issues — without focusing much on unions — full-time labour reporters are an extinct species. As a result, most Canadians know little about the contributions of unions to establishing and maintaining decent wages and working conditions, pensions, job security, health and safety measures, women’s equality, family leave with pay, and on and on.

We tend to take these benefits for granted, but all had to be fought for. As the colourful sign outside the Steelworkers building in Trail, British Columbia, proclaims: “Unions: The Folks That Brought You Weekends!!” And while labour history is stirring stuff, rife with struggle and sacrifice, it is a history we are losing. Not even academia pays it much mind these days. Thankfully, the field is not entirely barren: Ron Verzuh’s Smelter Wars and Earle McCurdy’s A Match to a Blasty Bough are welcome reminders of what working people are capable of, no matter the powerful forces arrayed against them. These books cover events in two very different eras on opposite ends of Canada: the resource-rich interior of British Columbia and the coastal fishing communities of Newfoundland and Labrador. Read together, their stories are that much more alluring.

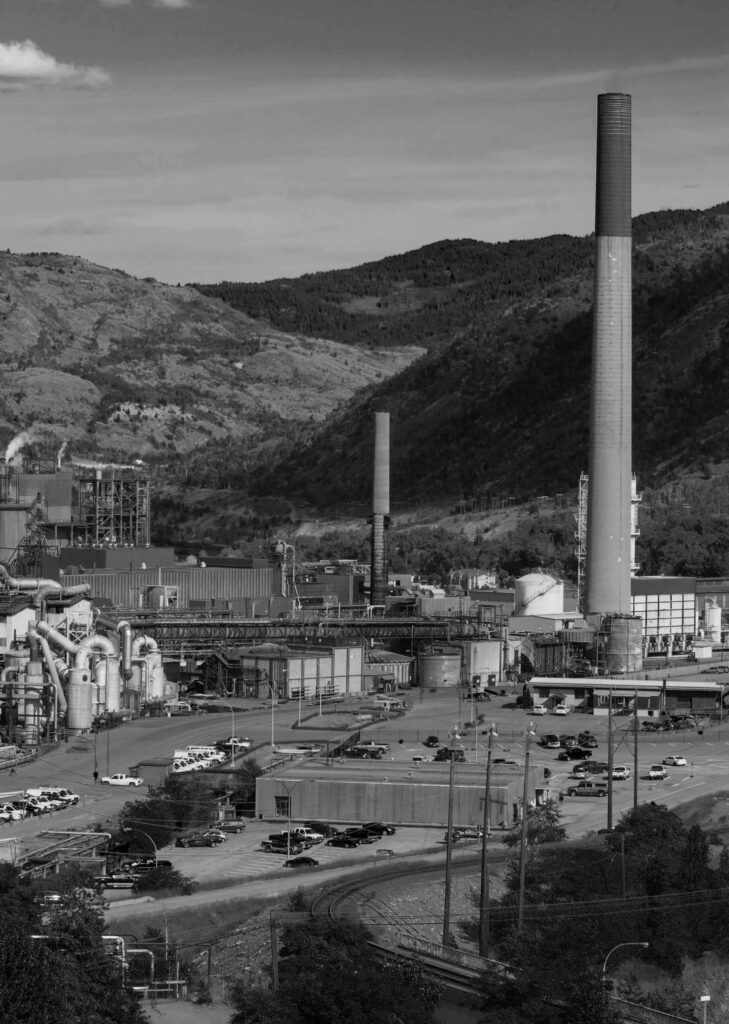

Scenes of a stirring history.

Murray Foubister; Flickr

Verzuh, whom I know as a fellow labour historian, focuses narrowly on the fierce ideological battle for the hearts and loyalty of workers toiling at what was for many years the world’s largest lead and zinc smelter, in the West Kootenay city of Trail. Amid the McCarthyism of the 1940s and ’50s, Local 480 of the Communist-led Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers was confronted by a raft of anti-Communist forces, including rival unions, RCMP agents, hostile media, the Church, and the powerful Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company — or Cominco — which was overseen by a rabidly anti-union president. Together, these forces mounted a relentless campaign to get rid of the Reds. There were no strikes and few disputes at the bargaining table. This was warfare of a different sort.

McCurdy’s book, on the other hand, seems to have a strike, protest, or occupation on every other page, as it recounts the dynamic fifty-year history of the Fish, Food and Allied Workers Union, from its modest beginnings to a pivotal role in Newfoundland’s 500-year-old fishing industry. Today, decision makers bypass the union, which McCurdy once led, at their peril. Forged in struggle, this is a union that, early on, adopted “Fighting back makes a difference” as its unofficial motto.

As a landlubber based on the West Coast, I confess that my own understanding of the FFAWU and its exploits was sparse beyond what I knew of the calamitous cod collapse and ensuing moratorium and the occasional highway blockade or boisterous rally that would sometimes make the national news. After reading McCurdy’s inspiring account, however, I venture to say this union, which embraces both economic and social roles on behalf of its diverse membership, has few equals as a fighting force in Canada.

Despite the precarious state of the cod stocks, Newfoundland’s fishing industry still hauls in more than a billion dollars a year, and the FFAWU has fought against centralization and consolidation to ensure this wealth is distributed fairly. The union has stayed true to the vision of its founding president, Richard Cashin, who declared in 1978 that it “has to go beyond the collective agreement, beyond the price of fish. It has to deal with the type of society we have.”

Cashin, a charismatic lawyer and former member of Parliament, set out in 1970 along with his friend Desmond McGrath, a socially minded Catholic priest, to smash the existing power structure of an industry that had been in the exploitative clutches of St. John’s merchants since the nineteenth century. Together, they sought a fair share for fishing communities and those who did the actual work. Achieving their goal did not take long. Cashin, who headed the FFAWU for its first twenty-three years, likened the response to “a match to a blasty bough,” the vivid phrase that McCurdy borrows for his title. At the union’s well-attended founding convention, delegates threatened to strike if fish harvesters were not given the right to negotiate prices — a right that West Coast salmon harvesters have never achieved. Legislation was passed three weeks later. The notorious truck system that had kept fishers in thrall to the fish companies for decades was gone forever. “The newly minted union was off to a fighting start,” McCurdy observes.

The next year, the members had their first strike. Plant workers in the outport of Burgeo took a stand for a contract against an employer who refused to recognize them. Defying a court injunction that limited picketing, they confronted strikebreakers and galvanized public opinion. In short order, the owner left town, the government nationalized the plant, and the workers had their first contract. “Never again will we beg,” proclaimed a triumphant picket sign.

McCurdy details breakthrough after breakthrough, as plant workers, inshore harvesters, and trawler crews united under the same banner. Confrontations were many, including, on one memorable occasion, a protest at sea to demonstrate against illegal fishing by foreign fleets, an event that brought international publicity.

In the midst of it all, catastrophe struck. The bountiful stocks of cod that had sustained Newfoundland’s vital fishing industry for half a millennium fell victim to years of greed and overfishing by efficient trawler fleets and virtually disappeared. It was, said Cashin, “a famine of biblical scale.” McCurdy’s account of the collapse, its impact, and the union’s prolonged, desperate fight for better programs and compensation is the highlight of the book. That fight paid off. Communities survived. When crab and northern shrimp rebounded — as a by‑product of the dwindling of cod, their dominant predator — the union battled successfully to ensure that inshore fish harvesters received a guaranteed share of the catch, which kept local plants open.

McCurdy spent thirty-seven years working for the union, with nineteen as president, but he says little about his long leadership role. What he relishes from his ringside seat is the battle-scarred members’ innumerable fight-backs. Yet his narrative never feels one-sided. His account is straightforward and enhanced by interviews and quotes from union members, befitting the work of an author who started off in journalism.

The setting for Verzuh’s book could not be more different than the small outports of Newfoundland. There is no bracing sea air amid the fumes and hot, miserable conditions of Trail’s sprawling smelter, which has loomed over the city from its clifftop perch like a Hollywood set for more than a century. Verzuh knows the place well: he grew up in the West Kootenays and put in shifts at the factory when he was eighteen.

In 1944, after a six-year campaign, Mine Mill Local 480 had finally overcome Selwyn G. Blaylock, the plant’s hard-nosed boss, along with his pet company union, to organize the workforce and negotiate their first contract. The next ten years, however, brought anything but peace. Postwar McCarthyism and Red-baiting were soon in full throttle, and Mine Mill came under incessant attack, not because it was a lousy union (it wasn’t) but because its leaders were Communist.

The union had already been kicked out of the mainstream labour movement for having the wrong political beliefs. At the heart of Verzuh’s interesting book is the decision the 3,700 smelter workers of Trail, few of whom were committed Communists, needed to make: whether to stick with an organization that was facing a barrage of outside propaganda and anti-Communist sentiment.

Even Pierre Berton joined in at one point. Verzuh cites an April 1951 Maclean’s article in which the popular writer warns Canadians that Cominco’s secretive heavy water plant, which played a role in the Manhattan Project, could be open to Soviet sabotage and espionage, since workers belonged to a union run by the Reds.

Like many of those in Newfoundland, the battle was a local one. But in Trail, it was also worker against worker: fought out in the bars, on the street, on the shop floor, at meetings, in the media, and sometimes at home among divided families. Verzuh details it all, with bonus sidebars on Mine Mill’s role in organizing a legendary concert by Paul Robeson at the Peace Arch border crossing, after the singer was refused entry to Canada, and the showing of the highly praised but banned pro-labour movie Salt of the Earth, written, directed, and produced by blacklisted members of the Hollywood Ten.

The charge to oust Mine Mill was led by the United Steelworkers of America, with its ties to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, whose membership included some of Canada’s fiercest Cold Warriors. The Steelworkers poured money and resources into a series of raids and urged workers to abandon a group they accused of being more aligned with the far-off Soviet Union than with local smelter workers. Heading Mine Mill throughout this period was its famed national president, Harvey Murphy, who was not without flaws but was nonetheless one of the era’s most skilled and capable labour leaders. A diehard Communist, he once described himself as “the reddest rose in labour’s garden.”

In the end, a majority of the workforce would not be stampeded by the Steelworkers, who eventually decamped in 1955. The workers stayed true to Mine Mill, because, Verzuh argues, they considered their left-wing leaders good trade unionists, who were focused far more on Local 480 than on opposing NATO or supporting Soviet-endorsed “Ban the Bomb” petitions. Verzuh is critical of the labour movement for ostracizing Murphy and Local 480 Communists. In so doing, he contends, “the movement lost its chance to effectively challenge capitalism’s hegemonic grip on the post-war economy.”

Smelter Wars and A Match to a Blasty Bough are significant contributions to working-class history. They outline events at the grassroots level and underscore the benefits unions can deliver to their communities when workers stand together. Thanks to the good wages negotiated by Local 480, for instance, Trail had, for a time, the highest per capita income in Canada.

Both Verzuh and McCurdy point to women as fundamental to union success. In the case of Local 480, a robust Ladies Auxiliary had its own campaign and refused to take a back seat to some of the more chauvinist leaders in pressing Mine Mill’s agenda — though Verzuh is critical of union leaders for doing nothing to save the jobs of hundreds of women who were laid off when the men came home from war. And in the fish plants, no battle was won without strong support from the female members, one of whom, Lana Payne, was recently elected president of Unifor, FFAWU’s parent organization and Canada’s largest private-sector union. McCurdy observes with satisfaction that in recent years, the percentage of women among those reporting fishing incomes has increased from 15 to 30 percent.

While the fishing grounds of Newfoundland remain relatively busy, Trail retains few vestiges of its storied labour past. The smelter is down to a thousand employees, while the Steelworkers are comfortably ensconced in Mine Mill’s old headquarters, the two bitter foes having merged in 1967. Verzuh laments the small city’s diminished working-class consciousness, seemingly a feature of a bygone era. But given the growing political challenges of today, he suggests the contemporary labour movement could do worse than “rekindle the spirit of struggle and resistance that Mine-Mill Local 480 displayed in Trail so many decades ago.” Perhaps he’d be cheered to know that very spirit remains alive and well on the other side of the country.

Rod Mickleburgh is a labour historian and host of the podcast On the Line: Stories of BC Workers.