When a conversation becomes a monologue, poked along with tiny cattle-prod questions, it isn’t a conversation any more.

— Barbara Walters

The black and white footage begins with a medium profile shot of the subject, who sits in an executive-style leather chair. A female voice asks a question from off-screen to the left: “Mr. McLuhan, do you like TV?” As the University of Toronto professor starts to answer, he gently spins around in the chair, while the camera dollies in and cuts to a jarring close-up. He answers laconically, “Oh yes, why shouldn’t I? Any reason why not?” The camera now cuts to a position behind Marshall McLuhan and slowly pans. In the background we can see a wall of flashing electronic panels, like in the final scene of 2001: A Space Odyssey. This is interview as science fiction movie, author talk as alien encounter.

The next question comes from a man’s voice off-screen to the right: “Have you ever taken LSD?” McLuhan responds at greater length this time. “No,” he says. “I’ve thought about it. I’ve talked with many people who’ve taken it. And I have read Finnegans Wake aloud at a time when takers of LSD said that is just like LSD. So I’ve begun to feel that LSD may just be the lazy man’s form of Finnegans Wake.” Cut to a shot of the studio audience, which is made up primarily of young people in jeans, T-shirts, and scruffy jackets. Laughter erupts.

I became somewhat obsessed by this clip during the lockdown of winter 2020–21. Ontario’s schools were closed, my young children were learning (or not) from home, and I was teaching my undergraduate classes on Zoom. My house was a mess, my emotions were scrambled. Even basic professional tasks like answering email felt like trying to read Finnegans Wake on acid. Just as billions of others were doing, I made up for a lack of social contact by diving headlong into the seemingly infinite depths of YouTube. Rather than becoming radicalized by extremists or hornswoggled by conspiracy theorists, I spent my time exploring a vast treasure trove of clips from old talk shows. Instead of the torrent of bile and invective and dark mutterings about secret pedophiliac plots orchestrated from pizza parlours in Washington — as the less salubrious corners of the internet would have it — I entered a halcyon world of charm and erudition, wit and glamour.

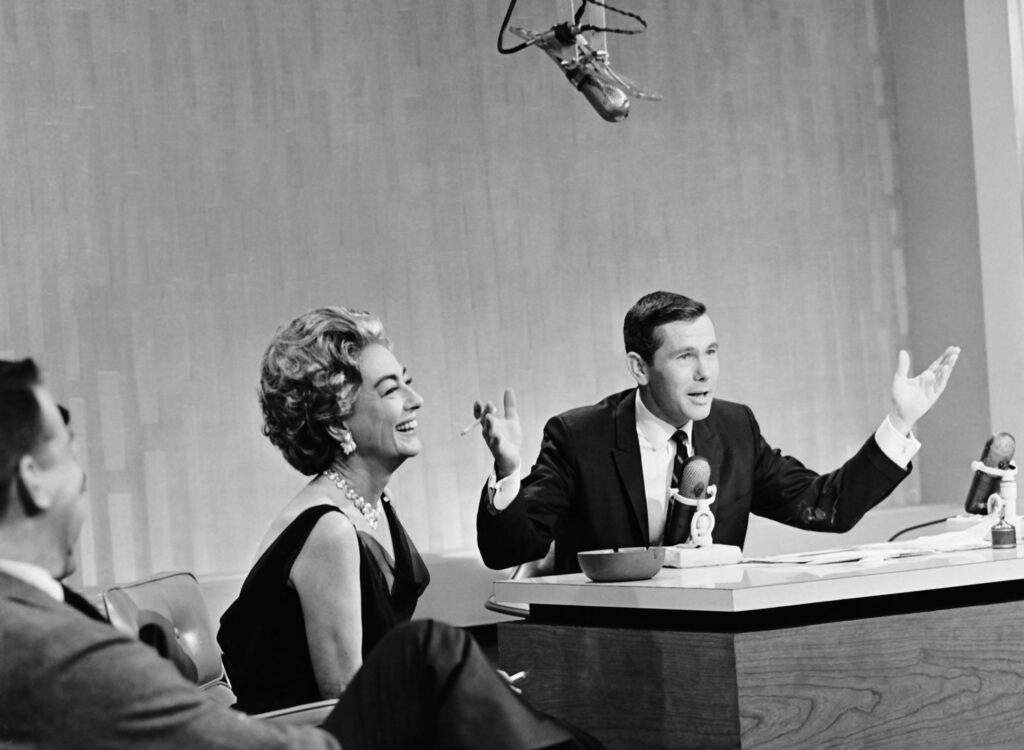

Joan Crawford and Johnny Carson on October 1, 1962, his first episode of The Tonight Show.

NBC; Getty Images

Looking back from the perspective of today’s media landscape, that McLuhan interview, which the CBC aired in 1967, seems like a relic from a lost golden age. I would define this era of broadcasting as falling between the mid-1960s and the early 1980s, when viewers regularly watched such giants as Johnny Carson, Dick Cavett, William F. Buckley, and David Frost, as well as Joan Rivers, Barbara Walters, and Mavis Nicholson, who were less celebrated but no less capable. (In Canada, renowned figures like Tommy Banks and Barbara Frum hosted comparable programs, though clips of their greatest hits haven’t migrated to YouTube in quite the same way.) This was a time when a sixty-minute episode featuring an actor, a novelist, and a champion boxer might attract an audience of nearly 10 million. Guests were drawn from the realms of literature, science, and the arts, along with the glitzier reaches of Hollywood, sports, and current affairs. The mixture of personalities and viewpoints was part of the appeal.

Executives at ABC tried to scotch the first episode of The Dick Cavett Show before it was broadcast in March 1968, because “nobody gives a shit what Gore Vidal or Muhammad Ali think about Vietnam.” Thankfully, Cavett and his team stuck to their guns; as it turned out, audiences eagerly wanted to hear what Vidal, Ali, and their fellow guest that evening, Angela Lansbury, had to say about the Vietnam War — and about their childhoods, careers, tastes in clothing, favourite holiday destinations, opinions on art and literature and philosophy, and just about anything else that might come up in the course of an hour’s unscripted conversation.

It is not difficult to see why I found old talk shows so appealing during the long days of lockdown, with my kids roughhousing in the next room. Everybody was trying to escape from their immediate surroundings at that point of the pandemic, but even that doesn’t fully explain why I gladly spent hours at a time listening to Groucho Marx spinning yarns about the New York garment trade and to Noël Coward and Lynn Fontanne reminiscing about provincial repertory theatre. Indeed, classic clips of Carson, Cavett, Buckley, Frost, Walters, and Nicholson have been circulating widely on social media for years. The vast majority of comments that accompany these clips dwell not on COVID-19 restrictions but on the charm of the guests, the grace of the hosts, the high intellectual tone of the exchanges, and the way sharp disagreements were, for the most part, handled with respect and civility.

In our current era of junk culture and political polarization, the golden age of the television interview has become the stuff of prestige drama. Consider Peter Morgan’s stage play Frost/Nixon, from 2006, which earned an Oscar nomination when it was adapted for the screen two years later (with Michael Sheen and Frank Langella in the title roles). Audiences and critics alike took pleasure in the high stakes of six-plus hours of conversation between the British journalist David Frost and the former American president Richard Nixon, conducted in 1977 and broadcast to some 45 million viewers. (Though the audience proved unprecedented, the three major networks in the United States had turned Frost down. He had to sell his interviews to individual stations, including the three-year-old Global Television Network.) There is also something appealing about the idea that journalistic rigour — and an expert interviewer’s forensic technique — could play a role in shaping history. Similarly, the 2015 documentary Best of Enemies, about William F. Buckley and Gore Vidal’s heated on-air exchanges during the 1968 United States presidential election, was adapted for the stage in 2021 and played to packed houses at London’s Young Vic Theatre.

It is right to be suspicious of anyone who claims that some prior epoch was a golden age of anything, whether it be talk shows, family values, civil discourse, or whatever else they find lacking in their own time. Cultural nostalgists have been projecting their unfulfilled desires onto the past at least since Hesiod wrote Works and Days, which descanted upon the “golden age” of peace and harmony that existed in some mythical time prior to the poet’s degraded present. Even back then — some twenty-eight centuries ago — things seemed to have been better in the good old days. Nostalgia is a comfort, yes, but it can also be a trap that tethers the misty-eyed modern to the reactionary desire to make talk shows or family values or the nation-state “great again,” usually by ignoring the real conditions of history.

In many respects, the way interviewers and their subjects talk has changed for the better since the ’60s and ’70s. It is hard to imagine a guest on a chat show today having to put up with the sexist questioning that Helen Mirren faced in 1975, when she was asked by the BBC’s Michael Parkinson whether her large breasts were an impediment to her being taken seriously as an actor. And when watching Richard Pryor’s mordant look at the audience after the celebrity physician Lendon Smith, who joined him on Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show in 1979, joked about how he often lied to his Black patients when he was unable to identify rashes against their dark skin tones, one wonders how a guest in 2023 would deal with such racial insensitivity.

In fact, what makes Frost/Nixon and Best of Enemies so compelling is their subtle ambivalence about classic broadcasts, rather than their credulous nostalgia. On the one hand, they showcase the seriousness and eloquence of the better kinds of past programming; but on the other, they point out how the oppositional style of these now legendary interviews laid a foundation for the hyper-partisan nature of so much current affairs broadcasting today.

Vidal versus Buckley made for good television not because they eventually reached an amicable concord, nor because their conversations revealed some hitherto unknown truth. On the contrary, it was the conflict that was the main attraction: how the two speakers so clearly articulated opposing, perhaps even irreconcilable viewpoints. Infamously, when Vidal accused his conservative colleague of being a “crypto-Nazi,” Buckley lost his cool and hit back: “Now listen, you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi, or I’ll sock you in the goddamn face and you’ll stay plastered.” Buckley later regretted this outburst, and commentators tend to agree that his misstep constituted a victory of sorts for Vidal, who had, intentionally or not, drawn out the latent bigotry of the reactionary right. This moment of hot-tempered invective does seem to have been a sign of things to come. Passion and anger are essential parts of politics, but when raw animus is the dominant mood, the mass media becomes what the historian Richard Hofstadter once called “an arena for angry minds.”

Watching old talk shows on YouTube offers the same kind of pleasure as watching Matthew Weiner’s period drama Mad Men. We get to measure the cultural standards of our own age against a simulacrum of the recent past, which turns out to be just as much of a foreign country as more distant epochs. What is most strikingly different about the classic age of the talk show is not the garish fashions (Joan Crawford’s pink tutu, for instance, or Lee Marvin’s flared suits) nor the smoking habits (from Anthony Burgess and his thin cigarillos to Orson Welles with his fat Cohibas) but the way people speak. We see a spontaneity and openness that seems sorely lacking on television today. Yes, the guests were there to sell a product, most likely a book or a movie but often simply their own charismatic celebrity. Yes, the hosts and their teams of researchers prepared for each show and guided the conversation with an eye on the ratings. Before the advent of modern media training and the suffocating dominance of the PR industry, however, there was more room for surprise on air. And more time for it.

True, the flow of conversation might have been interrupted at twelve-minute intervals by ad breaks. But today where could you find an entire hour-long TV show dedicated to conversation with just one or two artists, as Dick Cavett had with Ingmar Bergman and Bibi Andersson in 1971 or William F. Buckley had with Jorge Luis Borges in 1977? Long-form interviews can still be found on CBC Radio and, especially, among the vast number of podcasts that have sprung into existence in the last decade or so. Much of this content is excellent, though it is impossible to replace the language of gesture and response afforded by the visual medium of television. Gone, too, is the sense of occasion that once accompanied the rare presence of people like Bergman and Borges.

In the highly artificial but also curiously intimate arena of a host’s set, a certain kind of celebrity talker thrived. Gore Vidal, Truman Capote, James Baldwin, Muhammad Ali, Katharine Hepburn, Mary McCarthy, and Maya Angelou all bewitched audiences with various combinations of poise, intelligence, and subtle self-dramatization. Particularly charming or enlightening guests became regulars, honing their craft with each appearance. Some even enjoyed second or third careers as chat-show performers. During his late doldrum years, when he couldn’t get a film completed to save his life, Welles directed his gargantuan talent toward telling shaggy dog stories on late-night. Vidal quipped of Capote that as his celebrity increased and his literary output dwindled, he “more and more mastered the art of the astonishing interview.”

Perhaps, in some roundabout way, it was the low esteem in which artists and intellectuals held the still relatively new medium of television that lent their on-air performances such verve. Noël Coward, one of the period’s iconic raconteurs, observed that “television is for appearing on, not looking at.” Vidal added a dash of libertine glamour to Coward’s aperçu when he advised young writers to “never pass up a chance to have sex or appear on television.” Both comments suggest that while TV might offer cheap thrills, the true sources of cultural value lay elsewhere.

On-air critics and intellectuals seemed less eager to please back then, more confident that audiences would rise to their level rather than demanding a lowering of the tone. But some could be downright difficult. On two episodes of The Dick Cavett Show in 1980, Jean-Luc Godard expressed horror at his host’s willingness to tolerate the banal persiflage of guests night after night. The filmmaker took long, awkward pauses before responding to questions and repeatedly drew the audience’s attention to the artificiality of the set and camera equipment that encircled their conversation. His very appearance was an experiment in media criticism, a live deconstruction of the televisual by a master cineaste. (No wonder the segments are now staples of the online Criterion Collection.) When Anthony Burgess came on the show in 1974, he praised Cavett as “the only person on this kind of business who is concerned about words” and lampooned the late-night competitor over on CBS, “Vermin Griffin.”

The kind of long-form, free-range conversation that flourished in the ’60s and ’70s is vanishingly rare on late-night television today. Hosts like Stephen Colbert and Jimmy Kimmel command large audiences and often make the news with their satirical monologues, as did Trevor Noah before he left The Daily Show in December. But their interview segments are comparatively short, and most guests are too cautious or well coached to say anything genuinely interesting. Change the channel to cable news and the set-up is even less edifying. On CNN, MSNBC, and Fox News — as well as the BBC and the CBC — the quality of discussion seems to be of less importance than maintaining a hyperreal spectacle of “civil discourse,” which seems to unfold as though it were scripted by a not very competent artificial intelligence. Pundits and commentators are selected to represent “both sides” of political issues of such complexity and scale that they stymie all attempts at simplistic analysis. Politicians turn up armed with party-approved talking points and workshopped sound bites. Concerns that were first aired back in the ‘90s about “spin” and a new brand of slick media politics practised by the likes of Bill Clinton and Tony Blair seem positively quaint.

Thankfully, some public broadcasting stalwarts continue to fly the flag for serious conversation. When I moved to this country in 2010, I learned basic Canadian civics and got a pretty good sense of the cultural landscape by watching The Agenda with Steve Paikin on Ontario’s educational network, TVO. Paikin is a masterly interviewer, a calm and steady questioner of his guests’ views, a welcome contrast to the preening attack dogs I used to watch on the BBC when I was growing up. The Agenda, with its own YouTube treasure trove of content, performs a hugely important public service and is worth every penny of its relatively modest provincial subsidy, but even with all the best intentions, it is also (whisper it) a bit staid. A dash of pith and vinegar, a little salt and spice, to season the meat and potatoes of earnest debate would be welcome.

When PBS fired Charlie Rose in 2017 over sexual harassment allegations, the TV chatosphere lost one of its last links to the freewheeling style of Cavett, Frost, Rivers, and Nicholson. Although Rose hosted several world leaders and numerous other politicians around his famously low-lit table, his interests always seemed to lie beyond policy and current affairs. That intimate, smoky style of his was best suited to the more open-ended conversation of artists and thinkers. Rose’s interviews with David Foster Wallace and Spike Lee, among others, are masterpieces of the form.

It hardly needs pointing out that all conversation today takes place — to adapt a phrase from George Orwell’s classic essay from 1940 — inside the whale that is the internet. All of our public speech, whether it be on network television, on radio, or in a university lecture hall, occurs in a fully digital culture where everyone has the means of publicity and where constant commentary is the norm. Anything we say could end up on Twitter, Reddit, or RateMyProfessor. Whether we like it or not, our voices have been extended in space and time in unprecedented ways. The words that we utter, in speech or in writing, have the potential to traverse the globe in an instant and then live forever in Google’s data banks. The effect is twofold: A new kind of caution, a low-grade anxiety and self-surveillance that lead us to weigh all of our statements against their potential misconstruction by unseen audiences. And an ill-tempered lack of patience with the prissy strictures and artificial formulas that guard against such eventualities.

As audiences for traditional television dwindle, the function of contemporary talk shows is increasingly to provide short clips to be shared. The back and forth of sustained dialogue is cut up into one-sided rants and killer put-downs that are posted online and filtered by proprietary algorithms to suit the preformed opinions of distinct groups. Step inside the filter bubbles, and we find parallel communities with opposed but entangled world views. In the outer reaches of progressive social media, negative speech is cast as a form of violence. Online activists block contradictory voices as a pre-emptive strategy to avoid “harm.” There is a hyper-concern with the politics of representation, a kind of jittery, bad-trip version of that literary theory seminar you once took in university. Flip the polarity, and the online right is a rabble of faux-Nietzschean provocateurs and contrarian traditionalists, the strength of whose opinions is in direct proportion to their distaste for their opponents’ attitudes and beliefs. On the one hand, we have critical thinkers who de-platform their adversaries; on the other, we have free speech advocates who seek to ban books.

Of course, no one lives completely inside a filter bubble, and only a fool would assume that a 280-character tweet is an adequate statement of anyone’s actual beliefs. Just as people in the ’70s and ’80s occasionally switched off the tube and went for a walk in the countryside, most of us spend at least a couple of hours each day interacting with our fellow human beings and enjoying the strange pleasures of the immersive environment traditionally known as “real life.” The spectre of polarized online mobs is an abstraction, just like McLuhan’s claim that sixteenth- and seventeenth-century readers were “mesmerized” by the new technology of print or Walter Ong’s complaint that his students had been turned into zombies by their television sets. Media shapes our perceptions and influences our behaviour, but it is only ever part of the picture, a sub-routine of the total operating system of life.

Nevertheless, it is impossible to deny that we are currently amid a shift of profound significance. Just as the invention of the printing press helped to create the conditions for — not necessarily causing but making possible — the Protestant Reformation and the Scientific Revolution, so too are computer networks helping to usher in a new phase of human history. Maybe, somewhere over the horizon, a glorious age of knowledge and enlightenment will emerge from this transformative infrastructure. But right now we are more likely to have the sense that the expansion of digital media is creating a paradoxically shrunken conversational space, that our public dialogue is becoming clotted and congealed in warp-speed communication.

While it would be a fool’s errand to try to recreate the narrow, more cohesive broadcasting landscape of the ’60s, ’70s, or early ’80s in this age of digital fragmentation, there are lessons we might learn from the past and principles that we might apply in the future.

Many of the best talk-show hosts were humanists who combined an eloquence learned from classic authors with the brighter, sharper kinds of speech required for their medium. David Frost, for instance, read English at Cambridge in the 1960s. His tutors F. R. Leavis and C. S. Lewis, two of the giants of mid-century literary criticism, despaired that their pupil spent more time writing and directing comic revues with the drama society than preparing for his exams. In the end, he scraped a pass and went straight into studio, where he deployed his intellectual polish to hugely popular ends on the satirical show That Was the Week That Was.

Mavis Nicholson, one of the unsung masters of the interview form, was the daughter of a crane operator from working-class Port Talbot, Wales. She left to read English at Swansea University, where she was tutored by Kingsley Amis, who became a lifelong friend. Supposedly Amis, a noted conservative, coined the term “lefties” in reference to Nicholson and her husband, who regularly hosted boozy soirees at their North London home. In the words of another friend, “They invited people for an argument and threw some food in.” It is possible to detect the traces of both the spirited Welsh disputatiousness and the metropolitan literary polish in Nicholson’s interviewing style, which managed somehow to be both firm and soft at the same time. Her interviews with such figures as James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, Liberace, and David Bowie are exemplary for their curiosity, intelligence, and warmth.

And Cavett, once described as “a sensitive intellect of the talk shows” by the Globe and Mail, was known as the only man on TV who had read the complete works of Henry James. Occasionally, he would invite onto the stage his old philosophy professor from Yale, Paul Weiss, whom he likened to Socrates reincarnated. In one classic appearance, Weiss discussed racial politics with James Baldwin, arguing that the writer overstressed contingent social differences of race, class, and gender to the exclusion of the universal human task of striving for self-mastery. “The problem is to become a man,” Weiss stated, giving a TV-ready paraphrase of Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Spirit and the necessary process of Bildung. Baldwin responded by insisting on the inescapable presence of history in all men’s lives but most particularly in the lives of those who have been oppressed by the weight of injustice and social stigmatization. “I was discussing the difficulties, the obstacles, the very real danger of death,” he argued, “when a Black man attempts to become a man.” Unfortunately, Baldwin’s flow was interrupted by a commercial break, which underlined just how far Cavett’s set was from the graduate seminar room, let alone the Athenian agora; nevertheless, the segment offered the kind of robust but respectful difference of opinion that is all too rare on TV today.

The mid-century culture wars played out live on broadcast airwaves, rather than on partisan cable news or in the silos of social media. It was not just a matter of hosts and editors giving time to the tribunes of second-wave feminism, Black power, and the hippie counterculture; their guests — actors and writers, entertainers and star athletes — also interacted with one another, often to combustible and highly entertaining effect.

When he appeared on The David Frost Show in 1970, the activist Jerry Rubin took tokes on a spliff and observed, as his hippie comrades in the audience flooded onto the stage, that this on-air performance embodied the values of “the new society.” Perhaps Bette Davis had such a breach of decorum in mind when, on The Dick Cavett Show the following year, she reminisced fondly about the more refined manners of pre-war Hollywood: “As these beautiful people go, you know, it’s going to be a new world.” In many respects, it wasn’t party politics so much as the politics of conversation, the ethics of how to address and respond to others, that was up for grabs during the golden age of the chat show. Where the old guard tended to espouse the values of tact and civility, the younger, groovier, more bearded generation valued authenticity and expressiveness.

Buckley, one of the great figureheads of postwar American conservatism — and a man who once described his political stance as standing “athwart history, yelling Stop”— talked racial politics with Stokely Carmichael, Irish nationalism with Bernadette Devlin, the Vietnam War with Noam Chomsky, and psychedelic drugs with Allen Ginsberg. The quality of their discussions and the clarity of their views remain striking. Today, the conservative intellectual star is an exceedingly rare species, but Buckley saw it as his duty to argue face to face with his opponents and to respond to the best version of their arguments as expressed in their own words. The fact that Buckley’s Firing Line, one of the longest-running current affairs programs in history with over 1,500 episodes, aired on PBS rather than one of the major networks tells us something important both about the host’s cultivated bona fides and about the failures of commercial media.

For the most part, the conventions of civil discourse held firm. In 1970, Cavett hosted a testy encounter between Hugh Hefner and the feminist writers Susan Brownmiller and Sally Kempton. Over the course of their discussion, Hefner smoked his pipe and stressed his liberal credentials as a campaigner for abortion rights, while Brownmiller and Kempton argued for a form of female autonomy that wouldn’t require the support of soft-core gentlemen’s magazines. Hefner’s playboy liberalism was met by Brownmiller’s sharp but terribly earnest put-down: “The day that you are willing to come out here with a cotton tail attached to your rear end . . .”

But on occasion, the limits of both decorum and format were tested. In 1972, for example, Lily Tomlin simply walked off Cavett’s stage when her fellow guest, the actor Chad Everett, stated that his household was composed of three horses, three dogs, and a wife —“the most beautiful animal I own.” Tomlin knew that some people are simply not good-faith interlocutors. In 1980, Grace Jones, strung out after a long photo shoot and a heavy weekend of partying, lost her temper with the supercilious British host Russell Harty, resorting to what classical rhetoricians called the “argumentum ad baculum,” literally the argument to the cudgel. After Harty spent most of the show with his back to her, focusing his attention on his male guests, Jones started to physically beat the foppish (and chauvinistic) host.

The only example of de-platforming that I have been able to discover from back then occurred in 1972. At the eleventh hour, Angela Davis, the Black radical and former UCLA professor, decided not to appear on The Dick Cavett Show as scheduled, arguing that ABC’s requirement that she be paired with a conservative guest (the network wanted Buckley) would be inimical to the free expression of her views. Davis, a student of Adorno and advocate of the Frankfurt School’s critique of the liberal media’s soft tyranny, chose to opt out of the spectacle altogether, which might be taken as a harbinger of the post-liberal position on free speech adopted by some on the left today.

The most famous of all chat-show contretemps, though, was the encounter between Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal that took place on Cavett’s show the year before. Mailer and Vidal were long-time frenemies from the New York literary world, with a running beef about Vidal’s critique of Mailer’s response to women’s liberation in The Prisoner of Sex. They also had almost mythically antagonistic personalities: Vidal the dapper cosmopolitan wit; Mailer the brutish existentialist. In the course of their conversation, Vidal took exception to Mailer’s celebration of male violence as a source of spiritual truth: “What I detest in you [is] your violence, your love of murder.” Mailer, for his part, claimed that Vidal’s views were merely conventional: “It’s beneath us as Americans to think in thick, frozen terms of intellectual pollution.” Both engaged in a running game of double entendre that circled around Vidal’s homosexuality and Mailer’s phallic potency. Meanwhile, Janet Flanner, the author of the New Yorker column “Letter from Paris” and the evening’s “very, very bored” third guest, offered arch commentary from the sidelines: “You act as if you were the only people here.”

Things threatened to boil over, but fortunately the hour came to a close before any actual blows were traded. Legend has it that when Mailer and Vidal later met at a party, Mailer strode across the room and, without so much as an opening insult, punched Vidal in the jaw. Sprawled on the floor, Vidal uttered the immortal reply: “Norman, once again words have failed you.” If any single episode from the vast archive of old chat-show footage can be said to have attained the status of a classic, the one that preceded this exchange is it. Wit, excitement, and a pair of literary superstars slugging it out in front of an audience of millions. The days of giants have long since passed, dear reader.

Modern communication has become a kind of religion. If only we could communicate more clearly, more honestly, with greater empathy, via ever more refined technologies, then our social divisions and psychic wounds would be healed. “Only connect,” E. M. Forster told us. “It’s good to talk,” said the British Telecom adverts when I was a kid. Sigmund Freud devised a “talking cure” for our sexual neuroses. The United Nations enshrines intergovernmental dialogue as the solution to global strife.

In the words of the historian of ideas John Durham Peters, “ ‘Communication’ is a registry of modern longings.” Peters has also pointed out that, in the current high-tech media age, our ideas about the sharing of information can oscillate between utopian and dystopian fantasies. There is a tendency to see effective communication as a kind of fusing of selves, the perfect transfer of thoughts and feelings from inside me to inside you. We see this vision most clearly in the post-’60s focus on conversational authenticity and confession, the sense that if we find the right words, rid our minds of subterranean biases, open our hearts to the authentic flow of pure feelings, then we will all be “seen,” our inner essences rendered transparent to others. It was precisely this ideal that Yoko Ono espoused when she and John Lennon spoke with Cavett in 1971: “We can never have peace unless the whole world will have total communication.”

But at the same time, modern culture displays a dystopian preoccupation with communication failure. In the works of Kafka, Beckett, Ionesco, and Pinter — not to mention the Dadaists, the surrealists, and the deconstructionists — we find a distillation of the fear of never really saying what we mean and never really connecting with others. This is a nightmarish vision that edges toward solipsism, the predicament of the isolated ego locked in the prison house of language. When Godard joined Cavett in 1980, their conversation almost ground to a halt with his long silences and meaningful pauses. “It’s difficult to talk to people,” he almost whispered. “The trouble with interviews [is that] we feel obliged to speak. There is no silence.”

In our fragmented, bad-tempered, dumbed-down, always-on, globally networked, politically correct, informationally saturated, overly self-aware, dopamine-addicted, attention-deficient, post-liberal, angry populist, Marvel Cinematic Universe of a digital culture, we seem to oscillate faster than ever between the pathos of connection and the despair of isolation. We have the solipsism of the filter bubble and the confirmation bias of partisan media; we also have the humanist entreaty to reach across the divide and empathize with the other. As so many of us know from bitter experience, this duality was at its most acute during the pandemic lockdowns. Stuck at home, cut off from our kith and kin, we turned, in our isolation, to the internet, that vast and sprawling connection machine, which in bridging the gap between ourselves and our distant others only really served to emphasize the chasm between us.

In that 1967 CBC interview, Marshall McLuhan was asked why he sometimes disagreed with even his own pronouncements. His response might have seemed outlandish to viewers in the ’60s, when there were only a handful of TV channels and most people got their daily news from print, but as a prophetic vision of splintered digital media in 2023, it seems spot-on. “I have no point of view,” he said, still spinning in his chair and pointing to the flashing studio lights. “A point of view means a static, fixed position, and you can’t have a static fixed position in the electric age. . . . You’ve got to be everywhere at once, whether you like it or not. You have to be participating in everything going on at the same time. And that is not a point of view.”

There is a more modest understanding of communication that exists somewhere in the marshy middle ground between these utopian and dystopian extremes, however. This is the idea that communication is a learned art, indeed perhaps even a literary one. That it is neither a purely technological process nor a quasi-spiritual quest for perfect connection between self and other. This art has been honed over the long span of human history, adapted to new tools and media, reformed to meet the needs of changing circumstances. But it’s never been perfected. It is an art that everybody practises by instinct — most of us talk, write, gesture, and sign our way through our brief span of existence, usually without giving the process so much as a second thought — but some gifted individuals simply do it better than we do.

I suspect that it is this sense of conversation as an art form, conversation as a kind of non-purposive verbal play, that viewers like me find so appealing and instructive in the archive of classic talk shows — and so lacking in today’s media culture. At the time of their original broadcast, these programs were the epitome of disposable exchange, so much so, in fact, that NBC destroyed the tapes of the first ten years of The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson — erasing in the process what were surely priceless interviews with the likes of Peter Lorre, Count Basie, and Margaret Mead.

But the classic moments that have survived prove that, for all its ephemerality and evanescence, public conversation can achieve a kind of artfulness that makes it worth pursuing — and preserving. There are a handful of pure gems: Richard Burton sharing with Cavett stories about growing up in a Welsh mining community; Borges telling Buckley how Anglo-Saxon poetry compares with the street slang of Buenos Aires; Nina Simone sitting at a grand piano wearily explaining to Nicholson her desire to earn enough money to buy a home. Before the apocalypse comes, we ought to preserve such clips alongside the Botticellis and Picassos.

James Brooke-Smith is a literary critic and cultural historian at the University of Ottawa. His September 2019 piece for the magazine, “Meritocracy and Its Discontents,” was included in Best Canadian Essays 2020.