In the penultimate chapter of My Indian Summer, the twelve-year-old protagonist, Hunter, is shocked to learn that his mother, a residential school survivor, once wanted to become a nurse. He hates Margarette, after all. Her drinking, her abuse, and all her other parental failures make it impossible for him to feel safe at home, let alone loved. Knowledge of her past complicates things, and although he senses “something new under his anger and fear,” he’s not ready to think about what that means. Hunter is in survival mode, and he must flee his mother and Red Rock, British Columbia, the small northern town in which Joseph Kakwinokanasum sets his debut novel.

The year is 1979, and Hunter has been preparing for his escape — a goal that drives the first two-thirds of the book. He collects and returns glass bottles for the deposits so he can “turn Margarette’s messes into his profits,” and he barters with the kokums, a group of “Indian ladies at the edge of town.” They don’t just give him money, though. They offer him food and sometimes groceries brought by another trader. “When we have an advantage,” one of the women says, “we share with our people. Help one another, you know.” This, the characters understand, is the Cree way. It is also the logic underlying the intimate, relational microeconomy Hunter comes to rely on for sustenance.

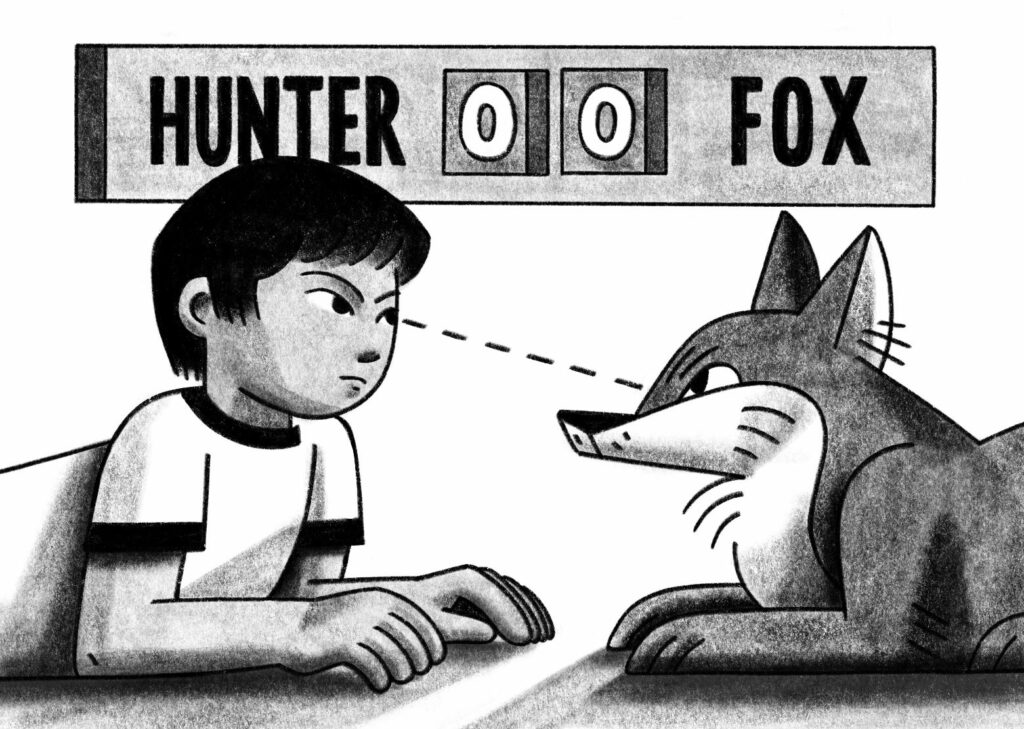

Kakwinokanasum frequently invokes customs and beliefs without further exposition, resulting in a narrative that fully immerses readers in the novel’s vibrant world. Mother Earth and Father Sky, for example, exhibit agency and even govern the lives of some characters, telling them “when it’s time to eat, sleep, shit, take a piss.” Animals, too, have their own agendas. While camping one night, Hunter finds himself in a staring contest with a fox who ends the standoff by saying, “I’ve got better things to do, you know. Meetings. Councils. Feasts. Important stuff.” The landscape and the creatures in it are more than just a mirror for the protagonist’s psyche. They live alongside him, and with him.

More than any other major character in the novel, the knowledge keeper Crow, another survivor of the residential school system, exists in harmony with his environment. Years ago, as a young man, he was arrested for possession of marijuana. While serving his sentence, he learned from a group of incarcerated elders “how to control the Black Wolf, how to nurture the White Wolf, how to smudge and pray.” Now he can give thanks to the Great Creator, watching the smoke from his hearth rise as he sees in the fading night sky a kind of “dance, a celebration of life before the dawn’s first breath.” He senses, too, “the rhythm of the land, the sky rhythms of the moon and stars, how it all connected to the rhythms of the animals, and plants.” He offers to teach Hunter how to make tinctures for various ailments and where to source the ingredients. A simple conversation can be “a quick lesson in the life of a Native living as close to the old ways as you could get.”

He encounters a fox with better things to do.

Gwendoline Le Cunff

If Crow illustrates one path for survival, then Troy Fernsby, a white nineteen-year-old, has set off on a very different, destructive one. When he was just fourteen, he stole money from his negligent parents and struck out for Vancouver, where he became a drug dealer — like his now deceased mother and father. He doesn’t blame the booze and pills for their failures; he blames their Cree customers. At the start of the novel, Troy decides to return to his hometown for Labour Day, because “in just one celebratory weekend, he could earn almost half his annual income.” Even though he despises the place, he sees it as a market to be exploited. The venture proves unprofitable, however, when he is arrested at a party. Troy manages to stash his supply by the river before being taken into custody, but Hunter and his friends discover, steal, and attempt to sell the drugs. When the dealer later encounters the protagonist, he says only, “I should’ve known it was a filthy half-breed and a bunch of savages that stole from me.”

Neither Crow nor Troy has a discernible character arc in the narrative. Instead, Kakwinokanasum depicts them as fully formed from the beginning — their actions determined by the decisions they made prior to the start of the story. Each of the men embodies a different way of life for Hunter to consider: one governed by idealism, the other by an insidious and irrational hatred. Crow seems to have embraced the flexibility required to live peacefully with others and the environment, whereas Troy comes across as an irredeemable bogeyman of colonial entitlement whose capacity for anything other than violence is limited to a few brief moments with his boss’s daughter, Charlize. In reality, of course, people who manifest this kind of hatred are multi-faceted and often capable of responses other than thinly veiled aggression. Racism is not simply a brutal aberration — a pattern of behaviour one sees in a few twisted reprobates. It thrives in far more quotidian, subtle acts of discrimination.

Despite the flattening, My Indian Summer is engaging, especially when we catch intimations of Hunter’s inner discord. Much of the plot and character development takes place only in the latter third of the book — leaving the narrative oddly paced — but Kakwinokanasum has a talent for depicting the protagonist’s and the community’s struggles to survive the effects of systemic oppression. Such stories are sorely needed, and this new author knows how to tell them.

Mobólúwajídìde D. Joseph is pursuing a master’s in geography at the University of Toronto.