Halfway through Slipstream, her intense, poetic, and candid memoir of her father, Rachel Manley referred, very much in passing, to her own first marriage in 1971. “I was briefly married to someone I had known for only ten days,” she wrote back in 2000. “I would pay for this when I found myself alone, pregnant and destitute in London, too proud to ask either my English or my Jamaican family for help.” In her equally intimate memoir of a beloved grandmother, Horses in Her Hair, from 2008, Manley mentioned the marriage again, just as succinctly: “At Easter I flew down to Barbados, where I met and married my first husband, whom I hardly knew, in a matter of weeks. My family was exasperated with me, and really, when I think about it, that was my design — to gain my father’s attention.”

Two tantalizing allusions — not mentioning her husband’s name, not even when revealing that she called their child after him “in the English tradition.” It is at the insistence of that child, now in his fifties and a successful lawyer, that Manley has written her latest memoir, George the Last, to share the details of the short-lived marriage and to try to better understand George Albert Harley de Vere Drummond.

At first glance, they might have been made for each other. Manley comes from Jamaica’s “first” family, her father and grandfather both former prime ministers, her grandmother Edna, a sculptor, one of the country’s most cherished artists. The Drummonds are Scottish aristocrats, tracing their lineage back to Attila the Hun and, more recently, the founders of Drummonds Bank. When they met, George was twenty-eight, four years older than Rachel, “a charming and reckless playboy with a lot of cash which he spent quickly,” on such ventures as the pioneering pirate radio station Radio Caroline, a motor racing team, and a film production company. On Barbados, he drove fast cars, played backgammon, always went barefoot, and seemed governed by the same determined irresponsibility as his new wife. Manley admits she could behave in “juvenile and obnoxious” ways, but George was entirely non-judgmental, even amused by her antics, his love for her unconditional. The only cloud on the horizon was an upcoming trial that took him back to England —“traffic tickets” being his mumbled explanation. Pregnant and suffering from morning sickness, Rachel joined him there on the day he was found guilty of handling stolen traveller’s cheques and sentenced to four years in prison. When they were eventually reunited, she writes, “I felt I was married to a stranger.”

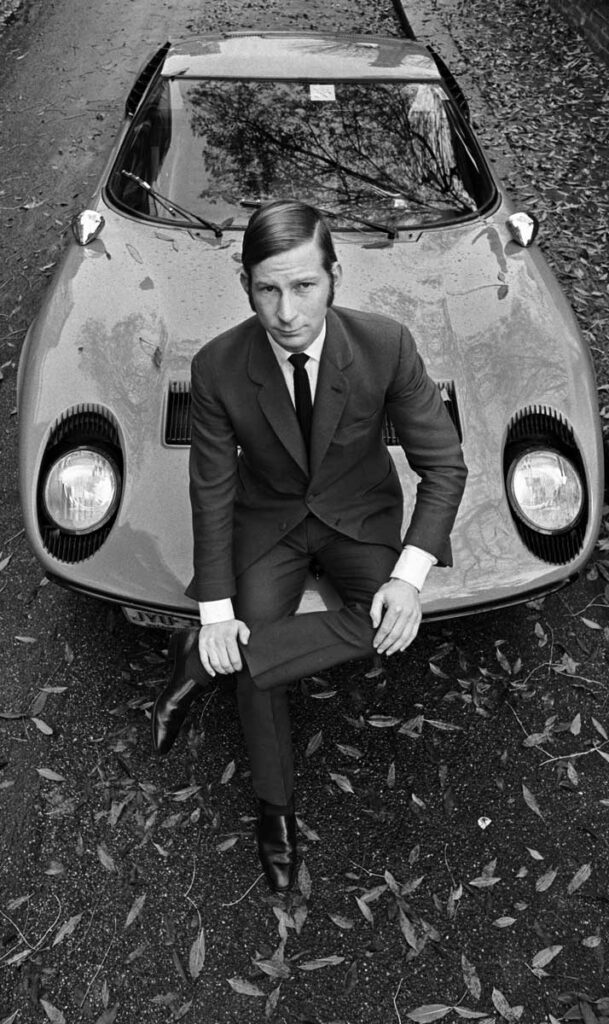

Drummond and his Lamborghini in 1967.

Lichfield Archive; Getty

Even halfway through the book, George is, to a large extent, also a stranger to the reader. In her earlier memoirs — especially Drumblair, which won a Governor General’s Award in 1997 — Manley brought her central characters to life through vivid conversations and deftly dramatized scenes shot through with her own astute analysis and emotional intelligence. Here, for more than a hundred pages, she barely lets us hear George, who spoke to his wife in soothing baby talk (“There, there, now Boos”) and muttered to his British friends “in the way British aristocrats do, snipping their words in two or three stuttered syllables and sounds.” But then Manley decides to let him have his say, through a series of the letters he wrote to her from prison and afterwards, reprinting them verbatim, without any comment or interjection. Sad and surprisingly eloquent, they show him coming to terms with the end of their marriage and accepting her new relationship with the man who would become her second husband.

After this epistolary interlude, the structure of the book changes again, with fluent narrative morphing into a collage of anecdotes, as generous, charming, diffident, and deeply unreliable George came and went in the lives of Manley and their son. He resumed his old ways on Barbados — more cars, girlfriends, nightclubs, and time spent with Tom Jones, Elton John, and other celebrities at the five-star Sandy Lane Hotel — and remained friends with Rachel. When her second marriage failed, he stepped up to help, renting a house where they could all live, together with his ex-wife’s new boyfriend. It seemed like paradise to Manley, but after two years they had to leave in a hurry: it turned out George hadn’t been paying the rent.

“It is easier to accept George as he is than to understand him,” Manley writes. “In George’s now long life he has managed to throw away or undo in one manner or another any gift or advantage life has given him by birth or thereafter by fortune, including those advantages he has created for himself.” And there Manley abruptly disappears from the book, at least for a while. We later learn that she remarried and moved to Canada, leaving her fifteen-year-old (known to all as Drum) to finish his school year on Barbados, under George’s watchful eye.

Drum then picks up the story, with unconnected episodes he calls “12 Tales of Life with My Dad.” These provide further examples of George’s eccentricity but not a great deal of insight into the man. As Drum puts it, “You seek him here; you seek him there. Everything remained a mystery. That was just who my dad was. You never really knew what actually happened with him. And that’s just how he wanted it.”

Thankfully, Manley realizes a little more explanation is needed. She returns to elaborate on earlier hints: that George was neglected as a child and learned solitary survival at boarding school; that his wealth, by allowing him to do exactly as he pleased, left him in “a state of free fall that deprived him not just of a sense of responsibility, but of purpose, of emotional investment.” His was a sort of “giant aloneness — even irrelevance — that made him not just unaccountable but uncounted — separate and emotionally disenfranchised.” As a summation, it is not entirely convincing. One longs to know more of what George has to say and what his own opinion of this mercurial, thoroughly entertaining book might be — for he is still alive, smiling rather shyly from a family photograph in the acknowledgements, in which Manley thanks him “for his love, generosity and tolerance . . . but most of all for allowing us to shine a light on him, attention he has never enjoyed.” Contradicting the last remark, she concludes, “George has asked us to encourage our readers to send him any new stories they may wish to share.” He even has her spell out his email address. The improbable aristocrat remains as unpredictable as ever.

James Chatto is a restaurant critic, author, and food and wine writer. His new book, Acquired Tastes: The Lives and Recipes of Eight Culinary Ambassadors, is due out in April.