In the spring of 2008 an academic colleague bemoaned to me the absence of materials on Canada-China relations that she could use in her teaching. There were a handful of books on the history of the relationship, occasional academic essays and think tank reports (mainly by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada), and a steady flow of media and other punditry, but dry the desert was.

What a change in five years. Academic books, mainly in the form of edited collections, are flowing: we have memoirs by Canadians, including Paul Lin and Brian Evans, on the front line of Sino-Canadian relations; virtually every major think tank across the country (the Canadian International Council, the Canada West Foundation, the Conference Board of Canada, the Fraser Institute, to name just a few) has published one or more reports focused on China’s rise and its implications for Canada with a heavy concentration on economics and trade. Opinion pieces about China and Canada-China relations are ubiquitous, with economics, democracy and human rights as their principal concerns. Even Norman Bethune has made a comeback, compliments of a biography by a former governor general.

How much of this outpouring has literary merit is questionable. But measured by bulk alone China is very much on Canadian minds.

And why not? In the past decade China has gone global in the blink of a geopolitical eye. The factoids are dizzying. China now is the world’s second largest economy and on a likely path to be the largest within a decade. It is the world’s largest trader and the largest trading partner of Japan, Korea, India and virtually every other country in Asia. It is the second largest trading partner of both Canada and the United States, and is on pace soon to surpass Canada’s two-way trade with the United States. Over the past eight years it has been Canada’s fastest rising trade partner, growing ten times faster than Canadian trade with the rest of the world. China is the largest consumer of steel and the largest producer of carbon dioxide emissions. It holds more than $3 trillion in foreign reserves and is the biggest owner of U.S. treasuries. China remains the largest destination for foreign direct investment and is moving into the top ranks of outward investors. One of its state-owned companies recently purchased Calgary-based Nexen for $15.1 billion, the biggest single investment ever made by a Chinese firm. China was one of the last into and first out of the financial crash of 2008, now accounting for about 40 percent of world growth.

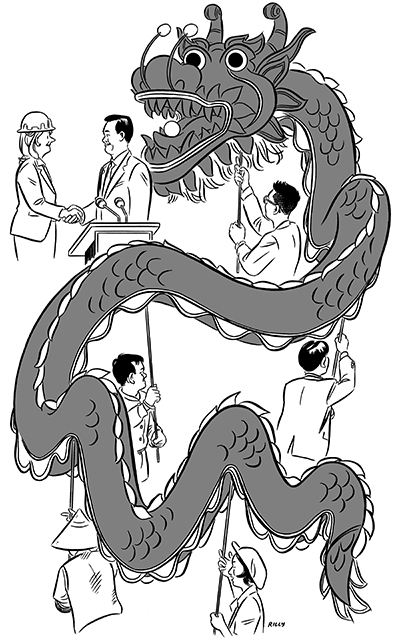

Ethan Rilly

In diplomatic terms, China has emerged as a serious player in virtually every major international institution, sometimes a leader. It is difficult to think of a global issue ranging from global warming and communicable diseases to trans-boundary water management, cyber security and non-proliferation where the road to a solution does not now run through Beijing.

The outpouring of words about global China is not unique to Canada. In most countries China is top of mind for politicians, publics and authors. For Canadians, China is no longer “over there”; it is right here on our doorsteps. We feel and see it when we walk the streets of our major cities, visit a shopping mall, think about our jobs and economic future, or take out a mortgage. The choices of the Chinese government, Chinese business leaders and Chinese consumers have impacts virtually everywhere. When I was a child in the 1950s, our dinner table discussion was about eating everything on our plate while remembering starving children in China, as if this would make a real difference to them. Thirty years earlier Pierre Trudeau’s first memory of China was putting nickels into a collection plate to save the souls of little Chinese children being supported by the St. Enfance movement. Today that dinner table discussion is about the competitive pressures and opportunities that China opens for our children’s future.

Despite vast differences in size, language, culture, tradition, civilization, history, and political, social and economic institutions, China has had special purchase on the Canadian imaginary from the time of Confederation. The biggest and most important dimension has been the human flows that started with the labourers coming to Canada to work on the railroad, the Canadian missionaries who flooded to China between the late 1870s and the late 1940s, the immigrants to Canada from greater China starting in the 1980s, the huge student flow to Canada (some 68,000 are now registered in Canadian post-secondary institutions) and the occasional reverse flow of Canadian citizens to China and its periphery with our young people in small but increasing numbers studying in China or, in larger numbers, teaching English in China and around East Asia. There is a pantheon of Canadian heroes in the relationship—Bethune and Dashan (aka Mark Rowswell, the television personality who has become Canada’s cultural ambassador to China) among them—with significant fan clubs among sinophiles in Canada and far larger ones in China.

Commercially, the eternal lure of the Chinese market for Canadian commodities and products has now morphed into something bigger and more complex: integration with China into global supply chains, China as a major source of investment, tourists, labour, and technological innovation and exchange.

Diplomatically, China has rarely been a top priority, except during occasional moments of Canadian engagement in Asian wars, as a recurrent Cold War problem focused on recognition and China’s admission into the United Nations. Yet now, with the exception of Canada’s relations with the United States, no other relationship is as complex, pressing and multidimensional at the levels of policy and management as China. Global China affects Canada in virtually every policy domain ranging from security and diplomacy through to First Nations affairs, fisheries and the Arctic.

Few doubt that Canada’s livelihood and prosperity, role in global and regional institutions, and exercise of leadership in the world will increasingly depend on getting China and China policy right. What should be our strategic response to global China? Should China be approached as a friend, strategic partner, ally, competitor, adversary or enemy? Can China become a responsible stakeholder in the liberal international order of market capitalism, democratic institutions and human rights that Canadians hold dear and that they have expended so much blood and treasure to underwrite?

For almost all of the period since Pierre Trudeau established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China in 1970, the high-policy answer to these questions has been engagement. Its underpinnings have been a calculation that engagement is preferable to containment, isolation or confrontation; a belief that Canada has both an opportunity and a comparative advantage in bringing China into the international system; and a wager that opening China economically would eventually induce political liberalization.

The special burden placed on engagement is that it was not only expected to produce commercial advantages and diplomatic leverage, but also that it was part of a moral enterprise to change China, to make China “more normal,” as was once described to me by a woman in a Tim Hortons line. This was the aim of our missionary movement a century ago, and so it remains for many Canadians who view human rights and democracy as the embodiment of universal values and institutions to which China should aspire and adapt.

Pierre Trudeau casts a long shadow. He gave Canada the foundations of an engagement strategy for dealing with communist China that held sway with his Liberal and Progressive Conservative successors and became something of a Canadian brand. But he also gave Canadians a charter of rights and freedoms.

China policy was bound to be vexed.

Particularly since Tiananmen Square in June 1989, media debate has been obsessed with a distinction between pursuing commercial and diplomatic opportunities with China versus promoting human rights. Other western democracies have wrestled with a similar issue, but it is difficult to think of a country where the tradeoffs have been so starkly framed in teeter-totter–like fashion, where the debate has raged for so long and where it has produced more complications for diplomats and politicians entrusted with managing the relationship. And far from disappearing at a moment when China’s economic leverage is in a completely different league than Canada’s, when the prospect of economic sanctions or punishment of China through trade instruments is unimaginable without horrific costs, our domestic debate still rotates around whether we should be having economic relations with a country run by a communist party.

Stephen Harper’s Conservatives came to power in February 2006 with a very different approach to China in mind. In a period of “cool politics, warm economics,” the Harper government moved to expand commercial relations with China through keeping the door open to Chinese imports, encouraging Chinese investment and investing in the Asia Pacific Gateway project to boost transportation infrastructure capacity for trans-Pacific supply chains.

Cool politics came in several forms. Various Cabinet ministers and ministers of Parliament described China as “a godless totalitarian country with nuclear weapons aimed at us.” The government immediately announced a principled foreign policy in which freedom, democracy, human rights and the rule of law would be the guiding concepts. Advisors spoke openly of shifting priority from communist China to democratic India. It took months for Chinese diplomats to meet with ministers. The first comments about China by the new foreign minister focused on espionage. The prime minister became personally involved in the case of a Canadian citizen of Uighur descent who was imprisoned in China and openly criticized China for human rights violations. He received the Dalai Lama in his office in the Centre Block with a Tibetan flag prominently displayed on his desk.

The approach produced a near diplomatic disaster. Official Chinese responses varied from puzzlement to anger. While several human rights non-governmental organizations and anti-communist groups supported the new approach, business leaders, academics and officials were nearly unanimous in condemnation. At precisely the moment that governments around the world were ramping up their connections with the PRC at all levels, Canada was in a class of one in reversing an engagement policy and depleting a reservoir of goodwill in Beijing built up over 35 years.

By early 2009 it was evident that the government was quietly and quickly reversing policy. The new line, remarkably similar to the approach of previous governments, was visible when Harper made his first trip to China in December of that year after a series of ministerial visits that the Chinese insisted were necessary to build confidence in the relationship. Ottawa took great pains to reiterate its “One China” policy. Harper raised human rights in his speeches but reverted to the established practice of dealing with individual cases in private. Words such as “friendship,” “engagement” and “strategic partnership,” banned from the official lexicon for three years, reappeared in the speeches of the prime minister and senior ministers. In perhaps the most symbolic move of all, the government provided significant funding for the upgrading of the Norman Bethune House in Gravenhurst, touting him as an exemplar of humanism and entrepreneurship.

The remarkable policy reversal has never been acknowledged, much less explained. Former officials have argued that this was less a reversal than a new course, part of a coherent strategy of rebuilding the relationship from the ground up through a series of bilateral agreements on trade offices, foreign investment promotion and protection, approved destination status and an economic complementarities study that have provided a new substructure to the relationship.

In many respects Canadian policy in 2013 is where we were in ambition and means at the time that Paul Martin and Chinese president Hu Jintao declared the strategic partnership between the two countries in September 2005. While the phrase is still used in Ottawa, the current version of the strategic partnership rests on different foundations. Some of the differences are particular to the Conservatives themselves. The ideology of anti-communism, universalist absolutism and the division of friends from enemies based on types of political system are deeply ingrained in the Reform/Alliance wing of the party. The philosophy of small government infuses a governmental interest in promoting transactions rather than building relationships. There have been no major investments in new programs for substantive policy dialogue, capacity building, or promotion of human rights and other Canadian values in China. The bilateral aid program for China is being phased out, with no government-sponsored successor focused on policy programs announced.

Reflecting the style of a prime minister with remarkable control over the making of policy, China policy is about individual activities, most of them commercial, rather than grand strategic plans or pronouncements. In the words of one advisor to the PM, “watch what we do rather than what we say and the pattern will become clear.” The strategic partnership is in fact an a-strategic partnership, very heavily focused on economic issues and without sustained attention to the major power shifts underway or the changing function and roles of regional and global institutions of which China is a part.

At the same time, wider public and intellectual support for the key premises of engagement is eroding. Polls conducted by the Asia Pacific Foundation and other organizations since 2008 reveal two main trends. First, Canadians think China is big, important and getting more so. Almost two thirds now believe that Chinese influence in the world will surpass American within a decade. They consistently overestimate existing trade with China and Asia, frequently by a factor of two or three. A little more than half now see it as an economic opportunity rather than an economic threat. Almost half favour a free trade agreement with China.

Second, they are worried about what a rising China portends. The sense of opportunity is leavened by a blend of uncertainty, anxiety and fear. Twice as many Canadians now have a cold or unfavourable view of China as compared to a warm or favourable one. China is consistently seen by a significant number of Canadians as corrupt, authoritarian and threatening and less than half think the human rights situation is improving. Concern about China’s growing military power is rising, and fewer than one in five favour a state-controlled company from China buying a controlling stake in a major Canadian company.

The recent controversy over the sale of Nexen to the Chinese National Offshore Oil Company revealed just how much of an exposed raw nerve that relations with China have become. Some of the criticisms of the sale grew out of a free market ideology averse to state-owned enterprises combined with nationalist concerns about domestic control of natural resources. The majority, however, focused on negativity about China itself. Mainstream and social media across the country, as well as voices within the Conservative caucus and Cabinet, opposed the deal because of CNOOC’s alleged connections to Chinese intelligence, espionage and the military. Critics brought into play arguments about China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea, its policies toward Tibet and Falun Gong, the vagaries of the Chinese justice system, trafficking in animal parts, the environmental dangers of shark fin soup and the health hazards of Chinese products. A popular narrative unfolded that doing business with Chinese SOEs meant dealing with the Chinese state, that the Chinese state was controlled by the Chinese Communist Party and that the Chinese Communist Party oppressed its people and violated their basic human rights. The cumulative fear of a rising China risks becoming greater than the sum of individual concerns.

The approval of the sale by the Harper government on December 7, 2012, was a triumph of clever politics and tactical compromise. But it did not lay the foundation for the energy dimension of the next phase of the strategic partnership or directly address the growing negativity about China.

Behind the negativity is a growing fear that a rising China poses a profound challenge to values and institutions that Canadians hold dear. Preston Manning framed the sale as part of a “deadly serious political competition with China” that “pits the well-developed Chinese Communist ideology of state-controlled capitalism and state-directed ‘democracy’ against the older Western ideology of market-driven capitalism and citizen-directed democracy. This competition is especially keen in developing countries where the West and China compete for resources.” The West, he added, “appears to be losing the competition.”

A few months earlier, Michael Ignatieff spoke in Riga about the “decisive encounter” of liberal democracies with post-communist oligarchies in Russia and China “that have no ideology other than enrichment and are recalcitrant to global order,” that are “predatory on their own societies” and that are “attempting to demonstrate a novel proposition: that economic freedoms can be severed from political and civil freedom, and that freedom is divisible.” As “Mao continues to glower down over Tiananmen Square,” commerce and capitalism, contracts and economic relationships have not dented China’s political system. He called for a “defiant stance toward the new tyrannies in China and Russia,” and approaching them as “the chief strategic threat to the moral and political commitments of liberal democracies.” But rather than seeing conflict as inevitable and eternal, he advocated responding with both curiosity and tolerance, avoiding the fixed categories of “us” and “them,” “[learning] from beliefs we cannot share,” and treating China as an opponent, not an enemy while practising politics, not war or religion.

Neither Manning’s nor Ignatieff’s approach closes the door on an engagement strategy, but both place limits and frame the encounter as an epic competition rather than an opportunity for deep collaboration.

Most of the recent writing by our China specialists is rather more upbeat. Study after study talk about the growing importance and influence of China in a full panoply of areas. They emphasize the pace and scale of change inside China, the prospects for collaboration in fields ranging from environmental management to rules for limiting the weaponization of space, and the possibility of convergence on rules and institutions based on shared and common interests. A trip to the Central Party School is more like a visit to an executive MBA program than a Marxist indoctrination centre. In many areas, including property rights, laws have been rewritten, judiciaries and legal systems improved, and in some instances rights respected in Chinese law upheld and enforced. China’s integration into the global economy is leading it, step by step, into “playing our game.”

The hard nut remains the system of government. Even as the Party transforms itself and the domain of personal freedoms expands, fundamental transformation of the political system through electoral mechanisms has stalled. China may no longer be totalitarian, but it remains authoritarian and is unlikely soon to evolve in the direction of western-style multi-party democracy.

Our missionary impulse to change China continues to run deep. It now encounters a China that is more wealthy, more powerful, more open and more outward looking than could have been imagined in 1970. Paradoxically, current expectations are much greater and more exacting than they were in the Mao period. For democratic fundamentalists, China is not a legitimate form of government, whatever the views of the majority of Chinese citizens.

The intellectual issue ahead of us is how to understand China’s response to the encyclopedia of acute domestic problems it is facing and its evolving global role. The great strategic issue of our times is not just China’s rising power but whether its world view and applied theory will reproduce, converge with or take a separate path from the world order and ideas produced in the era of trans-Atlantic dominance.

This calls for a 21st-century reprise of Canada’s middle power role. The policy challenge, beyond managing a myriad of pressing bilateral issues, is to facilitate a great power transition and foster rules, norms and institutions that allow an ascending China and an established America to traverse a diagonal rather than enter into direct confrontation. Earlier this involved getting China to as many tables as possible. Now it means extensive dialogues at the official, track-two and academic levels and exchanges at as many levels as possible.

The political issue is how a Conservative government that is ideologically anti-communist and philosophically ill disposed to strong national leadership can ramp up a relationship that will need imagination, clear articulation of goals and new resources. China needs explaining and Conservative Ottawa needs to make a case for why and how the strategic engagement of China needs to be played on a field much larger than commercial interests.

It will take wisdom, knowledge and political courage to update the strategic partnership and recast the Canada-China narrative. It will mean eschewing absolutes and being cosmopolitan in opening values and institutions, including our own, to constant interrogation and the search for common ground in a messy multi-centric world order shifting before our very eyes.

Paul Evans is a professor of Asian and trans-Pacific international relations at the University of British Columbia. His first book was a biography of John Fairbank; his most recent, Engaging China: Myth, Aspiration and Strategy in Canadian Policy from Trudeau to Harper, was published by the University of Toronto Press last year.

Related Letters and Responses

Charles Burton St. Catharines, Ontario

Bernie Koenig London, Ontario