Alison Loat and Michael MacMillan, like many Canadians, see a problem with our political system. In 2009, with MacMillan’s life experiences and financial means (he was co-founder of Atlantis Films and CEO of Alliance Atlantis), and with Loat’s talent and promise, they founded the charity Samara, “a think tank,” as they put it, “dedicated to raising the level of political participation in Canada.”

With colleagues, they began interviewing recently defeated or retired members of Parliament. “Conventional wisdom,” they reasoned, “holds that the best ideas for improving an organization reside in the minds and experiences of those closest to it.” Talking to MPs “would illuminate how Canada’s democracy works, right at its front line.” Each interview lasted two to three hours. They did 80 in all. The result is Tragedy in the Commons: Former Members of Parliament Speak Out about Canada’s Failing Democracy.

The former MPs gave them an earful.

The book is organized in the rough chronological order of an MP’s life, beginning with his or her nomination as a candidate. A riding nomination is democracy at its most grassroots level. Virtually anyone over the age of 18 can throw a hat in the ring. Virtually anyone in a riding can vote. It is a chance to get involved in the process, feel the excitement of a campaign, believe in something and someone. Feel Canadian. Monte Solberg, former Reform and Conservative MP, and Conservative Cabinet minister, tells the authors about that night in Medicine Hat. Solberg was manager of the radio station in Brooks, population 10,000, about one sixth that of Medicine Hat, an hour away. He had little chance to win. His supporters came by chartered school buses. The day went on and on. First ballot results were announced at 10 p.m. No candidate received a majority. There was another ballot. People began to straggle out. Except that Solberg’s supporters, having come by bus, could not leave. Solberg won on the third ballot by two votes.

Shantala Robinson

Imagine if all ridings were like that, Loat and MacMillan speculate. Politics would feel so close and real to so many people. It would be fun. They would want to take part. Instead, the parties get in the way (a recurring theme in the book). The parties want an open process, they say, but only as long as it produces the candidate they want. So they “encourage” a candidate—word gets around—and discourage all the others. For most people in a riding then—candidate, campaign worker or voter—why get involved? Why charter buses? Why feel anything but cynical about politics?

Loat and MacMillan are right. Politics would be better if party nominations were open. (In York Centre, Art Eggleton retired about a week before the writ was dropped for the 2004 election. At that moment, I presented myself as a candidate. There was no open riding election; I was appointed at the direction of the prime minister, Paul Martin).

The authors write about the experience members of Parliament have when they are newly elected. The MPs arrive in Ottawa full of excitement. They stand for what their party stood for in the election; they stand for what they promised their fellow citizens and neighbours in the riding. Almost without exception, they have no idea what they are getting into. They do not know the life. They do not know its impact on their families. They do not know how things work. (They do not even know that when they stand to ask or answer a question during Question Period, they have 35 seconds to do it—the standing, the applause from party-mates, the speaking, all in. I got cut off about halfway through my carefully written, thoroughly rehearsed maiden-answer).

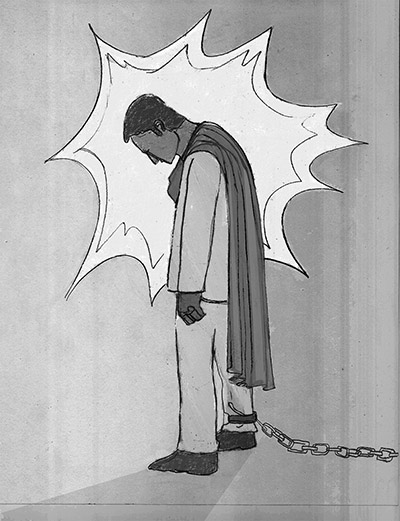

They come from backgrounds more varied than the authors assumed. Many are teachers, more are from business, some worked in the public sector, for non-profits or unions. Not many, to their surprise, are political “lifers.” But no matter their calling, almost all are known and respected in their field, often in their community. They are used to being seen and treated as special. They are not used to being told what to do. Now they belong to a party. A party that stands for this, and never for that. A party that has no chance ahead of time to decide whether it stands for hundreds of other things that life, and political life, throws up. How many of us, as accountants or car dealers, know much about free trade with Colombia or mandatory sentences? Private sector companies with a roster of 160 (the number of seats the Conservative government now holds), or 99 (the NDP) or 35 (the Liberals) have a core business. Their employees may disagree internally about what that is, but then they decide. Those who do not agree leave, or work with others to achieve those goals and present a united front publicly. MPs seem not able to accept this. Yes, it is hard to support a position you do not believe in. Yes, it is embarrassing in front of neighbours and friends. Those used to calling their own shots do not like it when they have to decide with others on what those shots are, or when others call those shots for them. On questions like gun laws or same-sex marriage, MPs as citizens may have held strong vocal opinions for much of their lives. If their party decides a different way, do they go with the party, or as is said on Parliament Hill, do they “swallow themselves whole”? Loat and MacMillan seem sympathetic. The party, again, is the bogeyman.

To feel themselves more than just cogs in a large machine, MPs “freelance,” seeking out niches on issues they can make their own—in their own mind, and in the minds of their colleagues and constituents. The price of gas, ATM charges, the Armenian genocide. They sponsor private members’ bills that will never pass, that they know will never pass; but when it is hard to explain what they are doing to a constituent, or to themselves, such actions can be made to seem achievements.

Loat and MacMillan also relate MPs’ stories about House of Commons committees. Committees provide a chance for MPs to call expert witnesses, to ask them questions, to get into big issues deeply. Some MPs tell of their work that changed legislation or government direction. More tell of how, no matter how deep they delved, nothing changed. The government did what it wanted to do.

Loat and MacMillan are right. It would be good if newly elected MPs underwent a political “boot camp” to help them be more effective sooner at their new life. MPs’ skills can be better utilized. Committees can be more effective. They are also right that while Question Period arguably makes a government more accountable, inarguably it makes MPs look unserious, inane and worthy of disrespect.

The authors are wrong, however, about a point they make early, and often. “Ask people who work at demanding, stressful occupations,” they argue, “and many will say they could never do anything else. Doing what they do was a lifelong goal.” “Not the MPs we interviewed,” they say. These MPs planned on being teachers or business people or community workers. Not politicians. Even after they were elected most do not identify themselves as politicians. This must be because the public holds politicians in such low regard, the authors surmise (the only occupation held lower: internet bloggers in one poll they cite, psychics in another). These MPs insist on seeing themselves as “outsiders” to politics even as they are fully engaged in politics. This is “ludicrous,” say Loat and MacMillan. MPs need to change “the narratives they use to describe themselves.” If they do not believe in what they are doing, why should anybody believe in them?

It does not seem to occur to Loat and MacMillan that this is not simple deflection or escape from embarrassment. It does not occur to them that for all but a few years of their lives these MPs were teachers and business people, not politicians. That for most of them, it was in trying to make the school system or economic system better that they realized they needed to move outside the classroom and office, to have bigger, broader influence. To go into politics. Politics was a tool, not a life. Not an identity. Indeed, the authors themselves note that most who pursue politics for politics’ sake do not win election. They have too slight a record of achievement. The public sees through them. Would things be better if politicians were preoccupied through their adolescent and young adult lives with politics, not teaching or business? If they were “lifers”?

This is but one example of the problem of the methodology the authors employ. They interviewed a lot of people, but they did not talk to them long enough to know them well. The authors believe our political system is not working. They are embarrassed by much of what MPs do, or are asked to do. So they assume.

They also begin their book with one other large misunderstanding. They cite respected surveys of democracies around the world that rank Canada consistently near the top, and comment that “these rankings are increasingly difficult to square” with our voting trends. Fewer Canadians are voting election after election. “Canadians are checking out of their democracy in droves,” they write. But, of course, Canadians who are checking out of political life are checking in to innumerable other ways of engagement, from participation in community groups to the internet. Politics, voting trends, are not the only measure of our democracy. Indeed, evidence of its strength is that it is doing as well as it is without our politics.

There is no doubt that much of what the authors suggest, if implemented, would make the life and role of the MP, and the functioning of Parliament, better. Of course, the key words are “if implemented.” Identifying problems is easy. Those who identify them assume that by making them visible change follows quickly. Of course, it does not. The problems exist for reasons that have to be overcome. But the book’s expressed purpose is not to examine the life and role of the MP and the functioning of Parliament. It is to raise the level of political participation in Canada. The question is what would be different, if all these changes were made. Would the level of political participation rise significantly? Not likely.

Political participation is about citizens and their lives. Exit interviews with MPs are about politicians and their lives. This book is looking in the wrong place. What is it that citizens are looking for? Very few want a regular dialogue with their MP. Who has the time? What would make them feel less isolated, disconnected from something they know matters, that affects their life? What is possible, and therefore to them seems right? Once national politics could only be conducted at a distance. The spaces were great. The technologies to connect us—buggies, trains, cars, planes, phones, computers—were absent or insufficient. We had to elect people to represent us because we could not represent ourselves. We created systems and structures appropriate to what we had. What is possible now? To a citizen, therefore, what seems right? What systems and structures are appropriate now? By focusing on the past, the authors are missing the present, and future.

Alison Loat and Michael MacMillan are serious, capable people. It is likely that they, and Samara, will be an important political presence in the future. Sometimes we need to look in the apparently right, but wrong direction, to find the right one. They have much worthwhile work ahead of them.

Ken Dryden was a Liberal member of Parliament from 2004 to 2011. He played goal for the Montreal Canadiens during the 1970s. He is also the author of six books, including The Game and, most recently, The Class: A Memoir of a Place, a Time, and Us. He now teaches at McGill University and the University of Calgary.