Instinctively, we all know what’s funny. If we’re not laughing, it isn’t funny. The same thing goes if someone else is laughing and we’re not. It still isn’t funny. Funny is as incontrovertibly subjective as a quirk of sexual attraction or the taste for boiled cabbage. It is all in the response: our response. My response. As far as funny goes, the only laughter that really counts is mine.

In The 100 Greatest Silent Comedians, an exhaustive, piercingly observant and mercifully often really funny book about who did and did not make James Roots laugh over the course of a half century in thrall to a period (roughly 1910 to 1925) and style—which the author interchangeably calls both “slapstick” and “silent comedy”—the matter of funny is both implied and embedded in the ranking. “Funny” is the uppermost of the six numerical categories he applies for a possible total score of—reasonably enough—100, followed by “Creativity,” “Teamwork,” “Timelessness,” “Appeal” and “Intangibles.” While the more clench–bottomed among us may quibble with that qualitative system on the basis that it is pretty much across-the-board subjective—and, ergo, intangible—these reservations will matter only to those who are expecting a book about anything other than what has had James Roots in stitches for 50 years and why he thinks it did. Once divested of such expectations, the reader is freed to enjoy one of the finest books on this defining but woefully fading moment in 20th-century pop cultural history ever written.

That Roots cares enough about silent comedians to rank 100 of them in an exhaustive volume justifying and clarifying that ranking has both cultural and personal motivations. Created in a -competitive industrial moment, the silent comedies were (and are) always watched in another competitive moment—where we are either engaged and delighted or distracted and bored—and it is in the impression of this moment that Roots’s own best work thrives. The author is deaf, and he discovered in the silent comedies broadcast on his family TV a form of entertainment that allowed not only “full accessibility” (to employ a term Roots, executive director of the Canadian Association of the Deaf, uses in his practice as an advocate for the rights of hearing impaired). It ultimately matters less than the fact that the condition made him more intensely and immediately susceptible to something the rest of the world was letting slip by.

As acutely aware as Roots is of the criminally myopic nature of history in general and pop cultural history in particular—where the bruised value of endurance must always go bare fisted against the shiny muscularity of the new—his relationship with silent comedy is not about restoration as much as it is about revitalization. Roots’s silent comedies, the ones that still make him laugh anyway, are very much living organisms, and his book is less a museum display for their secure internment than a wildlife preserve for ongoing study, appreciation and argument against extinction. He writes about these near century-old movies with excitement and immediacy, as though every entry—even those on people he practically condemns for perpetrating near criminal acts of heinous unfunniness—was knocked out fresh, his home entertainment system still warm from this morning’s test of the funny principle. Charley Chase (number 4, 93 points)? Still funny as ever. Douglas MacLean (number 83, 32 points)? Still about as funny as a nocturnal leg cramp.

Gabriel Baribeau

Roots’s conviction is that the funniest of the silent comics—the top six are Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton (tied for first place), Laurel and Hardy, Charley Chase and Harold Lloyd—are as funny now as they ever were, which is to say that the best silent comedy is timeless. But in this book that statement is stripped of its customary careworn presumption. The fact is, nobody watches silent comedies (or any silent movies, for that matter) much anymore, and the statement that the best of them are timeless has not helped in the cultural currency department. If most history is lazy to the point of leaning passively toward mythology—what history becomes when it is ossified, stripped of context and complication, and accepted at face value like a park statue—pop cultural history is even lazier. When everybody accepts that the Beatles were the best pop group ever, Citizen Kane the greatest talkie achievement, Marlon Brando the finest screen actor or even The Wire the finest TV program, the presumed consensus has a hermetic effect. We are delivered of the obligation to actually watch or listen anymore because the matter is decided, the case closed and sealed shut. And the so-called “timeless” object might as well be dead.

Even wading into the most well charted of silent comedy waters, the place where the only remaining discussion is whether Chaplin’s or Keaton’s monument is taller, Roots gleefully splashes around, looking at the films, reacting to their performance, questioning how and why they work as they do. By way of elucidation, not to mention slam-dunk confirmation of why Keaton has prevailed as the more-likely-to-make-you-laugh silent comedian today, Roots offers this about him:

How good is he? No one can get laughs out of a flicker of the eyes the way Keaton can. A perfect example: watch his eyes throughout the scene in Steamboat Bill Jr. when his father takes him to a haberdashery to replace his silly college beanie with a real hat. The way he shifts his glance, without moving his head, tells us everything about his hopes; his glum expectation of being overruled; his thought that perhaps a taking-Dad’s-acceptance-for-granted attitude will be sufficient bluff to get his own way; his slow realization that his father is going to be a very difficult man to please in every way; his self-consciousness and plummeting confidence as he grasps the fact that his big-city sophistication doesn’t work in this small town; and even his thoughts distractingly drifting away from the topic of hats to the topic of that pretty girl. And he does it all funny (and tops it off by emerging from the shop with a compromise hat on his head that the wind immediately blows away). No silent comedian, and certainly no talkie comedian, and not even Chaplin, could match Keaton’s consistent and unflagging wit in ocularly conveying his character’s unspoken mental machinery.

Meanwhile Chaplin, as ossified a pop cultural monument as Mickey, Marilyn and Elvis, is restored to (celluloid) flesh but only on the condition that he earn his status all over again. As the Beatles did when they took to the London rooftops in 1969, Charlie’s got to audition. He passes, but with a catch: Roots nails what it was that made Chaplin so popular in his day, but also why that day has passed—why, in contrast to Keaton, Chaplin’s historical status might indeed trump his current utility in the funny department.

Keaton is the purer (not necessarily better) comedian. Being much less interested in exploring social problems and class distinction than Chaplin (the whole point of the Tramp character is that he is the lowest of the lower class, i.e., the homeless, jobless, and friendless misfit/outcast, whereas Keaton never explores the class implications of his own wealthy characters), Keaton focused all of his attention upon the mechanics of building gags, drawing loops of comedy, and constructing a rising tide of laughs.

What do these few sentences explain? First they tell us why the best of the best were the best: they understood the power of the moving picture medium as a means of conveying comedy as a systematic strategy for surviving a cruel and absurd world. These sentences also help reveal the fundamental difference between these two visual comedy gold standards: each comedian was inextricably rooted in a distinct relationship to the modern world, and their comedy was a matter of constructing a strategy for struggling against and getting on in that world. While Keaton was conceptual and contemporary, Chaplin was emotional and nostalgic—Keaton an architect, Chaplin more like a musician. But, like all the best comedy, the art of each was a matter of structure. In their respective ways, each understood that nothing was funnier than when it had its own internal organic relationship to a clearly delineated larger world: the world itself might be absurd, but the logic of functioning rationally within that absurdity—the strategy adopted by both of these guys—was where the comedy sweet spot resided. And so Charlie boiled, marinated, seasoned and ate a shoe, and Buster did not blink when the house he built collapsed into kindling. Both were simply acting reasonably under unreasonable circumstances. Finally, and not in any way inconsiderably, Roots helps us understand why so many contemporary viewers find Keaton funny and Chaplin not so much. Existentially, many of us are too distracted by our envelopment in the present to muster much longing for the past.

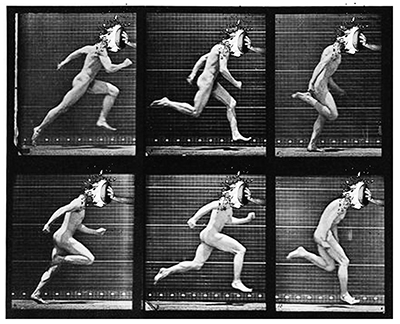

Silent comedies, made under Modern Times–like factory conditions to entertain (and make money from) early 20th-century audiences, were compelled by their limitations and industrial circumstances to levels of ingenuity, creativity and assertive artistic expression to generate sometimes astounding levels of comic achievement. Their timelessness, such as it was, was simply a byproduct of their hysterical competitiveness in the moment. For the best to become the very best, they had to stand out—be funnier, more brilliant and stick out—from a crowd that numbered in its peak literally thousands of titles and performers. Like so much popular culture, it was a matter of art emerging not only incidentally but therefore more spectacularly and indomitably. The best—the Chaplins, Keatons, Chases, Langdons, Arbuckles and Lloyds—were the best because they mastered the machinery, imposed distinctive visions upon their labour and fulfilled the fundamental task of making us laugh in the process, while the rest—which is to say the most—just got the job done. Timelessness was an accidental product of mastery in the moment.

Roots’s strategy of letting these movies live in the present, of unspooling before our eyes and imaginations through his, is his book’s most powerful argument for their continuing currency. The Keaton he loves—or the Langdon, Laurel and Hardy, or Charley Chase—is funny, right here and now, as much as he ever was. But is it a case that can hope for traction in the moment, when, more than ever, the films are likely to strike contemporary audiences as ancient, unfamiliar, irrelevant; when old must strain so mightily against the perpetual onslaught of the digital new; and when the false flattery of inhabiting the present moment has made ourselves (or, our selfies) the real subject of the movies our own lives have become?

The conditions for sustaining at least a certain vitality are there. There is, of course, the infinite capacity for digital reproduction and distribution: if any of the films Roots discusses exist in any form today, they are there to be seen on YouTube. This is no small development. As anyone who has spent sufficient time on the planet knows, there was a time—and not long ago—when one had to pursue archival pop cultural enthusiasms with the patience and diligence of an archeologist. Today I can test the response of an author’s funny bone with a matter of clicks. More significantly, I can do so in a world where, if anything, the conditions that inspired the best silent comedy—which is to say the act of spraying an individual tag on the monolithic walls of a mechanical and impersonal culture—can speak more loudly, even through their silence, than perhaps ever before. But if their struggles can still speak to us about our existential circumstances today, it is our response that is the ultimate sign of life. As long as we are laughing, no comedy is ever truly silent.

Geoff Pevere’s latest book is Gods of the Hammer: The Teenage Head Story (Coach House, 2014). He is the program director of the Rendezvous with Madness Film Festival in Toronto and is currently at work on a book about the mythology of rock music.