We live in a fretful age. Truth is custom-made. Cynicism swells. Tribalism scorches the middle ground. Institutions languish in disrepute, and so do facts. Authority figures are suspect, unless they are demagogues with a base.

At the same time, we covet knowledge and certainty. We wield our smartphones and GoPros like swords of vengeance, posting images of wrongdoing on public evidence boards such as Facebook and Twitter. The world’s great libraries of books and maps and artifacts and genealogy are easily searchable online — thousands of years of cultural wisdom at our fingertips. The latest scientific findings are just a swipe away.

This appetite for the incontrovertible lies uneasily with our taste for the fringe. Conspiracies thrive. Quackery is rife. Fantasy-driven gossip and unreal reality TV become narcotic entertainment. It is into this societal morass that Renée Pellerin launches an investigative tour de force about breast screening, Conspiracy of Hope.

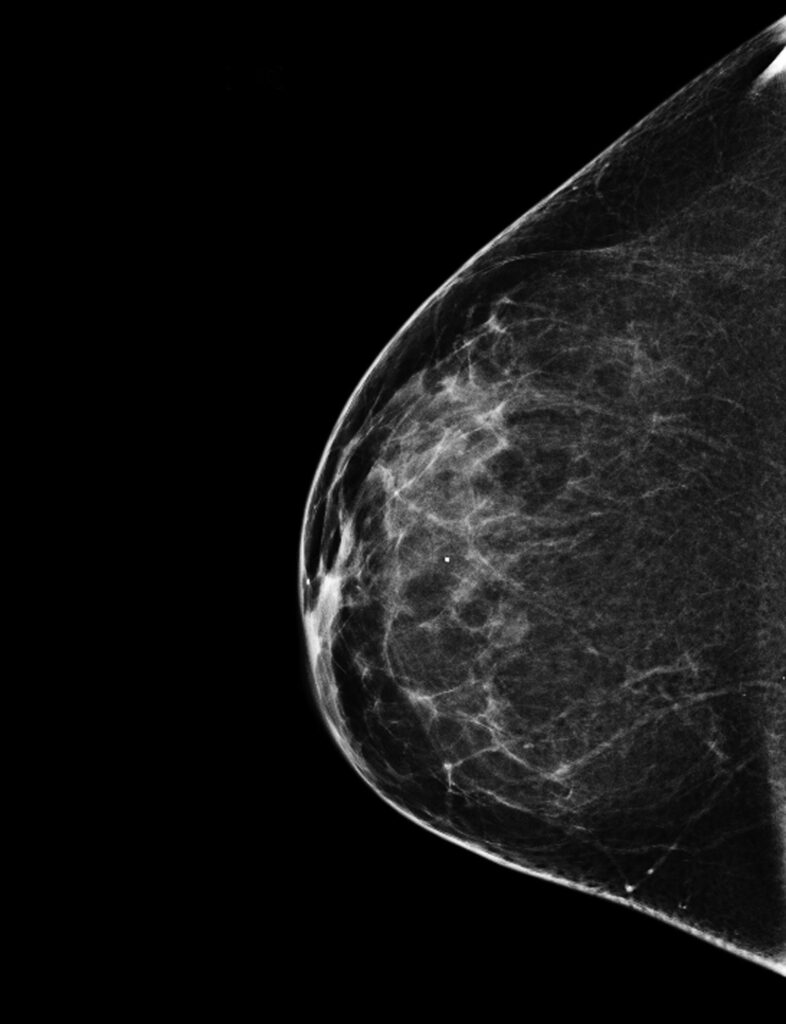

Breast screening began as a simple story: Starting in their forties or fifties, women show up every year or two for an X‑ray that peers deep inside the tissue of their breasts and finds any rogue cancer cells. Treatment follows. Lives are saved. Great success, and all because of a harmless ten-minute scan.

Far from a simple X-ray, breast cancer screening is knotted up with unsettled concepts of risk and reward.

National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health

But now this simple story has become confusing and opaque. Do mammograms actually reduce a woman’s risk of dying from breast cancer? If so, at what age should a woman begin the routine in order to maximize her benefit? It ought to be possible to weigh the evidence over time and come to a conclusion to these and other questions. But there’s the rub: consensus has turned out to be elusive. Instead, Pellerin writes, “no medical practice is as controversial or political as breast screening.”

Much like rebellions over childhood vaccinations, the topic of breast cancer screening is knotted up with unsettled concepts of risk and reward. How do we measure one set of risks against another? What is reasonable risk? Are we willing to settle for any level of risk at all? Must we have evidence of reward or only hopeful prospects of it? Where do we turn for that evidence in the first place?

Pellerin’s book becomes an exemplar of today’s impassioned conversations about the rights of patients, the rights of women to control their own bodies, and our faith (or lack thereof) in science and technology. All of it is nestled into such operatic themes as greed, hubris, revenge, manipulation, and triumph.

Mostly, though, what emerges is a story about old-fashioned fear and self-interest. That’s because routine screening is tightly wrapped in an unyielding mythology of cancer that doesn’t mesh with the reality of improved scientific understanding and treatment techniques. For example, even though 3 percent of women will die of breast cancer in Canada and elsewhere, the disease feels ubiquitous, loosed on an innocent population like a plague. I can attest.

Renée Pellerin is a journalist, which means she is trained to ask the questions not everyone wants asked. In 2014, as a current affairs producer at CBC Television, she and her team covered a study that updated the findings of a twenty-five-year-old landmark Canadian investigation on the efficacy of mammography. (She has since retired.) The study found that screening doesn’t save lives. It also can harm women whose cancers are treated, by surgery or radiation or chemo or a combination of the above, when they don’t need to be.

Outrage followed, with anger directed at CBC and other news organizations that covered the study, as well as at Cornelia Baines, one of its key investigators. Pellerin was perplexed. And that led her to wonder how the mammogram had become such a hot potato in the first place.

The truth she untangles in Conspiracy of Hope upends everything we’ve been told for decades. The push for screening began with an early randomized study that showed small differences in mortality among U.S. women who had been screened — to the tune of 0.07 percentage points, or fifty-two deaths in 32,000 unscreened women, compared with thirty-nine deaths in 32,000 women who were screened. Among women in their forties, there was no difference in the death rate.

That was in the 1970s, at the start of U.S. president Richard Nixon’s war on cancer. The study’s modest findings liberated huge government sums for breast cancer technology and screening programs, accompanied by an almost evangelical belief that any cancer — if detected early enough — could be excised and cured. A mammography juggernaut was launched.

Along with a paralyzing fear of early death, this juggernaut was swathed in female guilt and emancipation. It was both a woman’s right and her duty to have an annual mammogram starting in her forties, the campaigns adjured. One American Cancer Society television ad opened with a nod to the famous stabbed-in-the-shower scene from Psycho, with breast cancer cast as the remorseless Norman Bates.

Over the years, though, studies consistently showed no benefits of routine X‑rays for women under fifty, and not all that many benefits for women over. And while the mainstream medical establishment — both male and female — was wholeheartedly promoting routine mammograms, a few doctors questioned their actual benefits. Among them, Pellerin recounts in marvellous detail, was Charles Wright, a Scottish breast surgeon practising in Saskatoon.

As Wright looked at screening research in the mid-1980s, he concluded that mammograms did more harm than good for most women, and that only women whose risks for breast cancer were high — such as having a family history — should get routine mammograms. When he presented his findings at an overwhelmingly pro-mammography conference in Baltimore, he was shunned. One elderly radiologist even collared him, jabbing his forefinger into Wright’s chest: “You don’t understand, boy; you’ve got your hand in our pockets.”

Mammograms were already big business in the 1980s — especially for radiologists. Decades later, radiologists in the U.S. make an average annual salary of $400,000, placing them among the top medical earners, according to a Medscape survey. Throughout Conspiracy of Hope, Pellerin describes this lucrative “mammogram industry,” which is today worth $8 billion south of the border and hundreds of millions more across the Western world.

But passions aren’t all about the money. Meticulously, Pellerin tells of well-intentioned, compassionate researchers who wanted to save lives. Somehow, faith in mammograms ran ahead of the facts, and far ahead of public discourse about their limitations and risks. That’s what is meant by the book’s title: hope fuelled a conspiracy. Pellerin quotes Baines, the Canadian researcher, who describes “people who have been brainwashed to be afraid of breast cancer and have been brainwashed to believe that mammography saves lives.”

What’s more, the early detection of cancer may not have the life-saving effects we once thought. Roughly a quarter of cancers found by mammogram are ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS. These are tiny cancers at an extremely early stage, confined to the milk ducts. Treatments vary: remove the lump, remove the lump plus radiation, remove the whole breast. No matter how DCIS is treated, though, the outcome is the same: about 96.7 percent of patients are alive twenty years later.

But now there are questions about whether most of these DCIS lumps need to be removed at all. Many never get bigger or spread. Some don’t spread to the breast but eventually metastasize to other parts of the body. Regardless, finding DCIS through mammogram and removing it has done nothing to alter the incidence of new invasive breast cancers.

“It appears evident that if screening delivered anything beyond what improved treatments have accomplished over the last three decades,” Pellerin writes, “it is minimal.” She catalogues context and evidence that should make it possible for vested interests to recuse themselves from the discussion, for the science to shine through, for policy to change as findings are refined. That’s not happening. Mammograms are still routine in some jurisdictions, even among women in their forties. Across the U.S., women in their eighties are routinely screened, even as they are dying from other diseases.

As leading radiologists search for new technologies to find breast cancers even earlier, epidemiologists and cancer review boards in several countries are working to curtail screening. Such efforts are met with furious critiques — within the medical community and among fervent media commentators and the public. This all reflects today’s peculiar zeitgeist: “The debate over the ‘facts’ is unlikely ever to be resolved,” Pellerin writes in her most telling line, “because it’s about belief, not science.”

Has truth really become irrelevant in these unsettled times? Shall social media tub-thumpers reign? Does it really fall to each citizen to decide for herself which mammogram camp she is in, rather than trusting the people and institutions uniquely trained to assess the evidence? Which what‑if do we err on the side of: risks from radiation and false positives and overtreatment, risks from untended rogue cells, or risks of not challenging the status quo in the first place? Philosophical anguish aside, should I keep my damn mammogram appointment or not?

I moderated a public event about Pellerin’s book a few months ago, and that very question came up. She was refreshingly agnostic, given the entrenched positions in the debate she tracks. Her answer went something like this: There is no one-size-fits-all solution, so arm yourself with knowledge. Ask your doctor the tough questions. Make the decision that’s right for you alone.

Alanna Mitchell is a journalist, author, and playwright who specializes in science.