Canadian soldiers in the Great War, huddled in mud-filled trenches along the Western Front, had multiple words or euphemisms for death. A dead comrade may have “gone under,” “copped a packet,” or been “knocked out” or “buzzed.” Others may have been “napooed” or “kicked‑in.” In a macabre superstitious twist, touching a body part of a dead soldier, whose limbs might be protruding from the crater walls, could be a stroke of good luck. To carry money into battle could be asking for trouble. In a frightfully brutal world, where death was common, random, and everywhere, it is not surprising that infantrymen found their own ways to rationalize and describe the indescribable. Tim Cook’s The Secret History of Soldiers: How Canadians Survived the Great War is a study of their endurance and resilience.

Already established as one of the most popular historians working in Canada today, Cook blends rigorous academic research with an ability to tell a story well. And this is a story that he has been working on for years: How did soldiers survive months and months of trench warfare, in conditions that most sane people today would find unbearable? Why did they continue to fight for a cause that most people today find unfathomable? Why didn’t they just break down?

Cook takes issue with the categorization of Canadian soldiers as “victims” who suffered at the hands of bad generals, unthinking governments, malevolent economic forces, and imperial ambition. He instead portrays them as active agents in their own histories. He argues that they believed in the fight and coped with the extremes of trench warfare through the construction of a new kind of “culture.” Canadians, he writes, “met one another, served together, and relied on each other for survival. And, as part of their service, the soldiers had created a new and vibrant society.”

Living in close proximity in dangerous and unreal conditions, but isolated from everyone else, soldiers produced their own slang — a mixture of profanity-laced military jargon, euphemisms, and rude jokes, doggerel, and songs — which became “one of the building blocks to unit morale.” Through swearing, criticizing their superiors, and trivializing death, they fashioned a coping mechanism and a way of asserting a degree of control over their environment. It was also a way of bonding that helped improve the odds of group survival.

A unique trench culture helped differentiate Canadians from other military forces, especially the Brits.

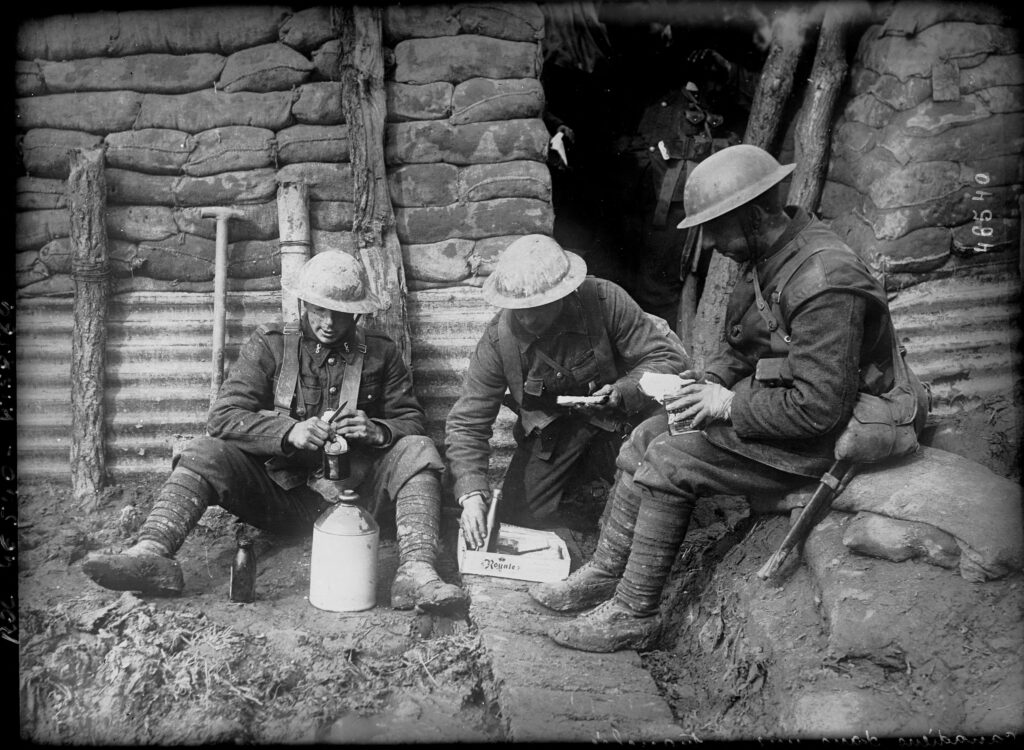

Bibliothèque nationale de France / Wikimedia Commons

Trench culture was experienced in multiple ways, and Cook delivers a series of chapters examining the poems and stories, gossip and rumours, songs and jokes, and more public expression in cartoons, graffiti, letters and diaries, trench newspapers, and theatre productions. Like slang, superstition was a common part of trench culture, and a great many soldiers put their lives in the hands of fate, premonitions, lucky charms, and other magical occurrences. Likewise, it was common for Canadian troops to rename their trenches after places back home and to collect souvenirs, including empty shells and enemy weapons. Collecting war mementoes seemed a peculiarly Canadian activity, and German prisoners reportedly commented, “The English fight for honour, the Australians for glory, and the Canadians for souvenirs.” (Our soldiers even had their own name for the practice —“souveneering”— though most souvenirs never made it back to Canada.)

Ted Glenn’s Riding into Battle: Canadian Cyclists in the Great War focuses on another group of front-line soldiers — ones who rarely found themselves in the trenches. Each division in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the CEF, had a small cyclist company attached to it, and in 1916 these companies were amalgamated into the Canadian Corps Cyclist Battalion. But with the Western Front mired in one long trench system, stretching from Switzerland to the North Sea, there were limitations on what a mobile force could do. As a result, the cyclist units didn’t actually spend much time riding bicycles, although they were there at Ypres in 1915, the Somme in 1916, and Vimy in 1917. Instead, they participated in other activities, ranging from traffic control to guarding enemy prisoners, carrying supplies, and burying the dead. At Vimy, they dug tunnels; sometimes they used their rifles like regular infantrymen.

The cyclists came into their own beginning with the Battle of Amiens, in August 1918, when the action left the trenches and became one of rapid movement and open warfare. The Hundred Days Campaign saw the heaviest Canadian fighting and the greatest number of casualties, and the Cyclist Battalion helped with advance patrols and reconnaissance; scouted roads, bridges, and other critical infrastructure (while sometimes securing and holding it); and communicated enemy positions back to headquarters. In the process, they faced snipers, enemy patrols, artillery, and machine gun nests as they cycled across muddy roads, abandoned trench systems, and devastated terrain.

Of the 1,138 men who served in cyclist units, 261, or 23 percent, were killed or wounded. Aptly, they nicknamed themselves the Suicide Squad. Recognized by Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie for their contribution, they were professional, well-trained, and experienced members of the CEF who worked alongside engineers, armoured cars, motorcycles, and cavalry units — all part of a new, professional Canadian military. Glenn’s book, a clear labour of love, preserves the memory of these relatively unknown soldiers who played a crucial role in the campaign that finally ended the war on November 11, 1918.

In September 1917, British Colonial Secretary Walter Long wrote to the governor general in Ottawa that King George V had hosted a group of Canadian soldiers for dinner, and had found their language “lurid.” According to papers in the U.K. National Archives, one soldier had said, “When we get back we will shoot Laurier and every d—d. French Canadian — cowards and traitors. We will have Civil War and exterminate the whole lot. Especially the R.C. Bishops and Priests.”

The king did not scold the Canadians for their explicit language or wicked intentions. Rather, he asked his government to “get some influence brought to bear on R.C. Church.” But the moment at Windsor Castle also revealed common aspects of trench culture: salty language and the soldiers’ general disdain for their fellow Canadians who had not experienced the war first-hand. King George’s guests, it seemed, reserved a special place in hell for those who refused to fight.

The First World War brought together a continent’s worth of classes, races, regions, languages, and religions, but for Cook and Glenn, differences were all but forgotten on the Western Front, where a new culture forged a single unbreakable bond between men. Trench culture “bound together this diverse force,” Cook writes. All the songs, slang, swearing, and jokes reinforced a mutual understanding of what it meant to be Canadian. “Never before had there been anything to bring together Canadians like the cauldron of war, and that terrible conflict forged a new Canadian nationalism.”

The bond between soldiers was strong, and it survived the war — with organizations such as the Great War Veterans Association and, later, the Canadian Legion. But is it too much to suggest that this mixing of classes, religions, regions, and languages sparked the creation of a new Canadian identity?

Among the young soldiers in these books: at least one governor general, two future prime ministers, provincial premiers, cabinet ministers, and other powerful politicians; influential journalists and businessmen; university professors; a famous Hollywood actor; and a range of other soon-to-be notable individuals who made up a surprisingly influential group that defined twentieth-century Canada. It is hard to imagine that war experiences failed to shape these men and their sense of identity (certainly many of them claimed that it did) or to impact the way they lived the rest of their lives.

Yet Cook is careful not to go too far. Trench culture reinforced the men and differentiated them from other military forces, especially the Brits. However, it was also a closed culture shared only by those on the inside. Even if you include everyone in the CEF, the 620,000 who served constituted a minority of the Canadian population. For every man who chose to enlist, there was another who declined. The war was a very different experience, one not especially synonymous with nation building, for many working-class Canadians, racialized minorities, conscientious objectors, and immigrants from enemy countries, as well as the majority of French Canadians.

If Cook and Glenn examine the ways soldiers coped in a dehumanizing war, Mark Osborne Humphries looks at those Canadian soldiers who could not cope and broke down. If there was anything that could undermine the bonds constructed by infantrymen, it was the soldier who refused to fight, or was seen as unreliable, unmanly, or cowardly on the front line. Men fought together and fought for each other; those who refused weakened critical ties, reduced the strength of the unit, and damaged morale.

With A Weary Road, Humphries deftly tackles the immensely complicated topic of shell shock: how it was understood and diagnosed, the divisions within the medical community, how treatment evolved over the course of the war, and how medical and military interests could collide (when thorough patient care was inconsistent with the military’s constant need for manpower). Into the mix are thrown cultural norms, class considerations, and the shifting understanding of masculinity and human nature.

Even today, shell shock — what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD — largely remains a mystery. A century ago, the military’s goal was to keep men fighting, so an invisible infirmity, whose diagnosis relied only on a soldier’s testimony, was perceived as a challenge by the military authorities. Solders, for their part, might see another’s claim of shell shock as a way to “moderate their participation in battle.” As a result, as the number of shell-shock victims increased, the military responded with policies focused on returning more and more soldiers to active duty.

By the later stages of the war, British authorities (the CEF medical services were part of the British army) banned the term “shell shock” altogether, and Humphries’s history becomes one of using other labels to diagnose and treat the same afflictions. There are few heroes or villains, however, and he demonstrates that authorities were not as oppressive as others have claimed. For the most part, this is a story of well-intentioned people working under extreme circumstances with limited resources — people who did their best to balance medical treatment with military demands.

It is impossible to know how many Canadians suffered from shell shock, given the variety of names under which it was classified and the various field ambulances, rest stations, and base hospitals where men might have reported or received treatment. Then there are all those men who suffered in silence. Regardless, it is clear that a relatively small number (about 16,000, or 4 percent of those who served overseas) were taken out of the line because of it, and it was never as important to the medical authorities as bullet or shrapnel wounds, or even diseases such as dysentery, influenza, and trench foot.

What is surprising, when reading these three books together, is not that some men broke down under fire — all were frightened and suffered from frayed nerves. Despite the camaraderie of trench culture, few soldiers could withstand a sustained heavy artillery barrage for very long. What’s surprising is how so many men continued to fight and carried on to the very end of the war. Part of the story was trust: Soldiers believed their comrades would fight on. They would have each other’s backs. They would be there to dig out and carry each other to safety if wounded. If a soldier trusted those around him, he could get through some of the worst trauma that war could inflict. Together, Cook, Glenn, and Humphries offer a fascinating glimpse into that defining process of coping, rationalizing, and enduring the ordeals of total war.

David MacKenzie is a history professor at Ryerson University. He edited Canada and the First World War and co-wrote, with LRC founding editor Patrice Dutil, Embattled Nation: Canada’s Wartime Election of 1917.