When I run past Coal Harbour or drive along its Dunsmuir Viaduct, I experience the results of what’s arguably the most consequential policy choice in Vancouver’s history. In February 1973, the city’s eleven-member council voted overwhelmingly against constructing a freeway through the downtown core. The decision arose from powerful forces beyond municipal institutions: namely, local opposition that impelled the Pierre Trudeau government to withdraw federal support for the project. However, it also signalled a tidal shift within those institutions.

Public antipathy toward the highway proposal had helped fuel the election, in 1972, of a new, more progressive political party, The Electors’ Action Movement, known as TEAM, which routed the long-standing pro-development, pro-freeway Non-Partisan Association. The new mayor, Art Phillips, brought to city hall a keen attention to the daily experience of city life. In an era of intense highway construction across North America, he helped swerve Vancouver onto an unusual back road of urban development — one that prioritized urban serenity over the car as king. To this day, British Columbia’s largest city remains the continent’s only major urban centre without a freeway feeding its core.

Like Toronto’s partially elevated Gardiner Expressway, completed in 1966, Vancouver’s proposed freeway would have severed its downtown from its waterfront. (The proposal’s only visible remnants are sections built before the 1973 decision, the Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts, located in northeast False Creek, near BC Place.) Quashing construction was good for lively street life and lovely vistas, but it produced a new problem. Without a highway, how would people travel en masse from their homes to downtown? The daily commute is a prime consideration for planners everywhere, but in post-1973 Vancouver, it assumed special importance. At the time, and well into the 1980s, Vancouver was suburbanizing in the typical North American fashion. Its downtown, rather atypically, held the city’s largest concentration of workplaces. A new form of connecting home and work — indeed, a new form of urbanism — had to be imagined.

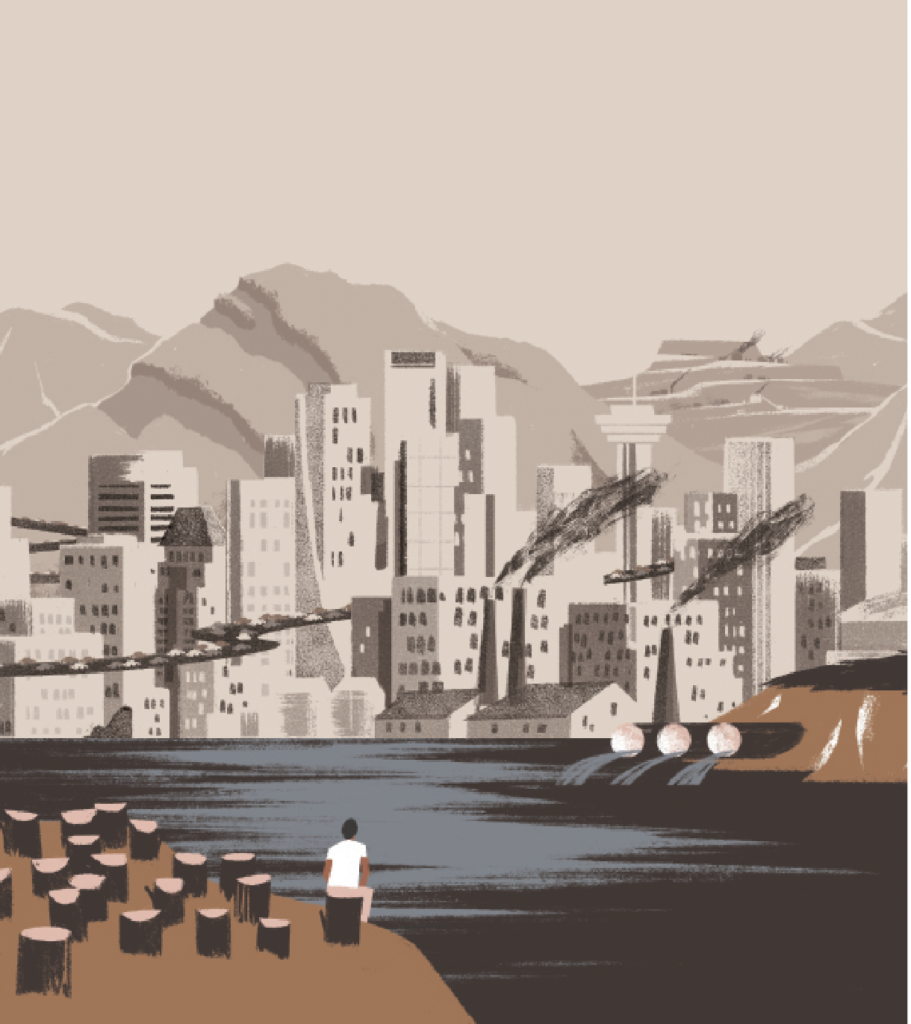

Vancouver could easily have become an unenticing place to live.

Christy Lundy

Larry Beasley’s Vancouverism documents that imagining. Prefaced by an illuminating essay from the journalist Frances Bula, which surveys the city’s history until the mid-1980s, where Beasley picks up, the book charts a remarkable development: downtown Vancouver’s transformation from a zone beset by suburban flight to a space of densified — and largely convivial — community life. As Bula notes, Vancouver developed in ways that set it apart from such western cities as Calgary, Edmonton, Winnipeg, and Los Angeles. These places, unlike New York, Montreal, and other constrained eastern cities, sprawled from their earliest years across the west’s open spaces in ways still reflected in their urban forms. How, then, did Vancouver alone stem the suburban tide? Why did it turn out so differently?

Vancouver’s unique geography offers part of the answer. Hemmed in by mountains and water, its downtown sits on a peninsula that constrains growth. History matters too. Located on the peninsula, right between the central business district and the magnificent Stanley Park, the neighbourhood known as the West End set precedents in urban density and architectural style that fuelled the later developments throughout the downtown. Despite earning a reputation for seediness by the 1970s, the West End was in earlier decades a coveted home for affluent apartment dwellers, who sought proximity to both Stanley Park and their offices. The notion of a livable core studded with slender apartment towers has long existed in the city’s civic imagination.

But circumstances of geography and history do not fully explain Vancouver’s distinct urban form. Make no mistake: specific policy interventions were essential to its transformation from the 1980s onwards. Beasley, formerly Vancouver’s chief planner and now a professor at the University of British Columbia, played a central role in hatching these policies. Vancouverism, then, reads as part memoir of a remarkable career, part lucid primer on planning principles that work.

Today, “Vancouverism” is widely used by urbanists to describe that special brand of urban density, livability, and sustainability. The term has no known origin or fixed definition, however. Beasley’s definition is expansive, encompassing deliberate policy choices for producing efficient land use; a socially diverse population; and an inviting, elegant physical design for urban living. His conception also embraces a spirit of collaboration among private real estate developers and the general public, whose experience of the city interests Beasley the most.

In Beasley’s hands, Vancouverism’s seemingly disparate parts emerge as a cohesive whole. Take the quandary produced by the rejected freeway: How do you transport people from home to work? At first glance, this might appear an isolated issue of transportation policy. Probe more closely, though, and it encapsulates an entire ethos of city life. Lacking a freeway, planners were forced to devise a new strategy for expediting the daily commute. Their solution was not to find some alternative transportation artery. Instead — and ingeniously — they decided to move homes closer to workplaces, thereby dramatically reducing the need for car trips at all. Downtown, they decided, must be densified.

In an era when public consciousness remained enchanted by the dream of home ownership and large plots of land, an era when many Vancouverites yearned for the local analogue to Calgary tract housing or Mississauga bungalows, Beasley’s team decided to market a wildly different bill of goods. To sell Vancouverites on downtown living, they had to render it unprecedentedly enticing. This in turn required beautifying densely populated zones through high-end urban design and the deliberate nurturing of a rich community life. Very quickly, a question of mere transportation policy has become a web of wide-ranging policy considerations.

And all these varied considerations themselves required bureaucratic engineering. Vancouverites not trained as planners might be unaware of the extent to which their everyday experience is calibrated from on high. When you catch a glimpse of the North Shore mountains through the mass of downtown towers, you encounter a view corridor designed with the utmost deliberation at city hall. Even the towers themselves, viewed from afar, are a work of bureaucratic artistry. Following public complaints about the flatness of Vancouver’s downtown vista, Beasley’s team began to study its overall profile. The resulting skyline now contains sculpted modulations: strategically placed taller buildings enlivening the scene. According to Beasley, Vancouver is the only city to shape its skyline so deliberately.

Perhaps the most astonishingly granular interventions occur at the level of individual buildings. Planners work with developers and designers to ensure daylight reaches every window of a new structure, and they see to it that the windows themselves are distanced from or angled to those of nearby buildings. They consider the acoustic effects of open space. Where possible, the primary living space in new residential units is distanced from public walkways. Beasley even muses that statelier sidewalk design will encourage more pedestrian trips.

Vancouver’s strictly regulated, deliberately planned downtown possesses an understated beauty that belies criticisms of glassy uniformity. Yet anyone familiar with Vancouver knows that the city is not without blemishes — some severe. For one thing, the Downtown Eastside exposes Vancouverism’s failure to produce meaningful social and economic equity. Skyrocketing housing costs, meanwhile, degrade quality of life for all but the wealthy.

To his credit, Beasley addresses these failures head‑on, grasping at solutions. On the issue of affordability, he is especially imaginative, proposing solutions not often heard in mainstream housing debates. Most discussions are fixated on an either/or: either buy property or rent it. But perhaps alternatives exist. Might co-housing and space-sharing concepts developed in Nordic countries, for example, work here? How about alternative forms of financing and development? Could buyers purchase a home without having access to capital gains, so that they build equity while starting from a lower price? Could the finance industry support new forms of shared ownership? Prompted by Beasley, we can begin to imagine an affordability program far more expansive than anything on offer from mainstream politicians.

Peculiarly, however, Beasley skirts a major theme in Vancouver’s housing debate, one given prominence by much recent research, including from Simon Fraser University’s City Program director Andy Yan, and by reporting by the real estate journalist Kerry Gold and others. That theme is the effects of foreign investment. Of course, Beasley need not endorse or rebut the widespread claim that foreign speculation has profoundly altered Vancouver’s housing market. Some prominent figures — especially those in the real estate and development industries — contest it. However, by not meaningfully engaging the claim at all, his discussion of housing remains incomplete.

What Vancouverism evokes is the trajectories the city could have followed but didn’t: possible but bygone futures latent in the Vancouver of the 1970s and ’80s. The Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts, seedlings of an unbuilt highway that are now slated for demolition, stand as monuments to such futures past. Indeed, the detailed techniques of urban engineering that Beasley describes allow us to imagine a city less consciously designed and regulated. This alternative Vancouver is one in which mid-century trends of suburbanization go unchecked and development proceeds helter-skelter, producing a fearsomely different experience — and one unenticing as a place for living.

Yet even more spectacularly worrying alternative futures existed than those Vancouverism implies. Can you imagine a Vancouver whose West End has, through breakneck development, become a West Coast Manhattan, complete with overcrowded sidewalks, shadowy canyons, and scant nature? What about one whose skyline is framed not by today’s verdant North Shore mountains but by clear-cut peaks or sprawling, Aspen-style ski resorts? This alternative Vancouver — Manhattanized and set against denuded, treeless mountains — would have a densely populated suburb, complete with row houses and a rapid-ferry commute, on nearby Bowen Island. Gambier Island, meanwhile, would be not the idyllic place it is today but the site of a mining operation worth billions.

These scenarios are not just revisionist fantasy. J. I. Little’s At the Wilderness Edge: The Rise of the Antidevelopment Movement on Canada’s West Coast shows developers and financiers advancing these visions for the city’s future, with varying degrees of plausibility, from the 1930s through the 1980s. Each vision faced stern resistance from Little’s main subject: a series of local and largely unconnected anti-development campaigns that bear an uncanny resemblance to contemporary environmental movements — reminiscent, but not quite identical. From Squamish to Gambier Island, from Bowen Island to Hollyburn Ridge, and even in downtown Vancouver, natural spaces slated for residential and industrial development galvanized protesters whose identities and motivations defy stereotypes we often associate with ’60s and ’70s environmentalism.

Like British Columbians who protest against the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion today, these mid-century groups fought to save nature from despoliation. However, their motives for environmentalism appear quaintly anthropocentric today. Ecological concerns of wildlife habitat and biodiversity were peripheral in their minds. Rather, these groups sought to protect natural spaces as zones for leisure activities, such as fishing or skiing. In an era of rising affluence and greater leisure time, one that birthed the term “lifestyle,” nature’s value lay above all in its benefits to psychological well-being. These older campaigns for nature, then, sit at an oblique angle to those of today. Even so, they nourished an ecological awareness that gave rise to contemporary environmentalism.

Some cultural historians treat resistance as a terminus to analysis, rather than a spur to new questions: that Group X or Text Y resisted entrenched power is noteworthy in and of itself, irrespective of whether (and why) the resistance succeeded or failed to effect real-world change. Little is no such historian. He charts the why, how, and who of these movements. Somewhat surprisingly, mid-century anti-development protesters were largely middle-class and upper-middle-class professionals; what we think of as major environmental groups, such as Greenpeace (founded in Vancouver) and the Sierra Club, did not participate in their campaigns. Indeed, anti-development leaders were not inspired by or compelled to cooperate with the New Left countercultural activism that arose in the ’60s. And many of them were women — a notable fact given the limited opportunities for female political participation at the time.

They succeeded in part through appeals to technical-scientific reports on the effects of development, through vociferous protests at local town halls, and through legal challenges. Their campaigns, that is, occurred within and alongside the very bureaucratic institutions scorned by the era’s youth counterculture. Unlike earlier anti-development campaigners in the province, what these groups sought after the Second World War was not nature’s conservation, a concept associated with more efficient resource use, but its preservation. By identifying spaces of wilderness upon which development must not encroach, ordinary middle-class British Columbians asserted limits to growth and boundaries to city life. Their protests, as Little suggests, reveal how urban life to some extent depends upon the nearby presence of the non-urban — a space imagined by self-interested urbanites as revivifying.

The city that Beasley and his fellow planners designed, and that ordinary citizens fought to shape through political engagement, is a marvel of North American urbanism. Born and raised in Vancouver, I left for university and came to appreciate how rare it is to find my hometown’s combination of abundant greenery, natural beauty, densified living, and serene pace of life. With most of my family still there, I visit regularly and wonder why I ever left.

But then I check housing prices. In January, the urban policy consultancy Demographia ranked the housing market second among the world’s least affordable. When I encounter fellow displaced Vancouverites, our common talking points have changed from ten or fifteen years ago. Back then, we would perform the smugness for which our ilk is known, comparing wherever we were unfavourably with our cherished city. Now, the tone, affect, and subject matter have shifted. There’s a wistfulness for what Vancouver was before galloping price escalation, a resentment of its arrival, and a grudgingly implied acknowledgement of the city’s beauty, as if vocalizing it would expose our sadness at having left. Many of the more recently displaced Vancouverites I’ve encountered have claimed, channelling Jessica Barrett’s much-read 2017 essay in The Tyee, that the city has lost its soul.

A common refrain among politicians, developers, and boosters is that Vancouver has become a world-class city. And yet I wonder: Do most Vancouverites want to live in a world-class city? I think of friends and family who have stayed or moved back. One gave up a thriving business career in a financial hub for much less certain prospects, all because he missed the sailing, skiing, and hiking. Others embraced the area decades ago as a retreat from the unbridled urbanism of larger places; some of these people feel that the city that has grown around them is no longer what they sought in the first place.

Perhaps a better question, and one addressed only obliquely by these two books: What kind of classiness best suits Vancouver? Should Vancouver aspire to be world-class in the same way as London, Tokyo, and Manhattan? To me — and, I believe, many others — what distinguishes the city is the elements that can’t be fully captured by the imperatives of policy making (“grow the economy,” “drive innovation”). Rather, it’s the vibrant community life, natural beauty, multiculturalism, and lifestyle opportunities that Vancouver offers.

The phrase “world-class” is often applied generically and ubiquitously, its meaning unchanged from place to place. Can Vancouver wrest “world-class” from this unchanging definition, redefine it in the interests of its populace, submit the term’s meaning to democratic deliberation? Beasley’s book gives me hope that it can. Vancouver has, for decades, forged its own singular style of urbanism. Little’s book, meanwhile, reveals a deep-seated civic will to ensure the city comes out on top.

Spencer Morrison is a professor of American literature at the University of Tel Aviv.