In “The Ruin,” an Anglo-Saxon poem preserved in the tenth-century Exeter Book, the speaker surveys the crumbling Roman city of Bath, marvelling at walls that survived kingdom after kingdom only to succumb, finally, to time. The speaker is so far removed from the Romans — and the secrets of their stone construction — that the buildings seem to be the work of giants, their ruin mirroring the fate of those who once lived in the city. He imagines them frozen in a moment of triumph, flushed with wine and gleaming “gold-bright” in elaborate armour. Such nostalgia for the rack of a previous age was so regularly employed in Anglo-Saxon poetry that they even had a word for it: dustsceawung, or “contemplation of the dust.”

Clyde Fans, the latest book from the acclaimed Canadian cartoonist Seth (otherwise known as Gregory Gallant), seems to belong to this tradition. It tells the story of two brothers — one cerebral and reclusive, the other angry and too practical — and the small business they are forced to steward when their father suddenly runs out on the family. Over the course of five sections, spanning more than fifty years, it charts — through the rising and falling fortunes of the two brothers — the path of a now endangered species of Canadian industry represented by a small Toronto-based firm. Think of the local companies that once competed with much bigger American counterparts in building and selling the simple goods that rapidly became necessary for middle-class twentieth-century life: glassware, kitchen appliances, and, in this case, fans — themselves appropriately doomed to near-obsolescence with the invention of air conditioning.

The book is structured around an epiphany that the quieter of the two brothers, Simon, experiences in 1957, while on a failed sales trip to the fictional town of Dominion, Ontario. Simon suffers from anxiety so acute that he rarely leaves the apartment that he shares with his mother. Because he lives a life with little outside stimulus, Simon returns to the town — and the people he meets there — again and again in his dreams and imagination. While the people of Dominion might have long ago forgotten him, he ultimately realizes, they will forever hold a special place in his mind.

The graphic novel is particularly well suited for the themes of labour and loss.

Drawn and Quarterly

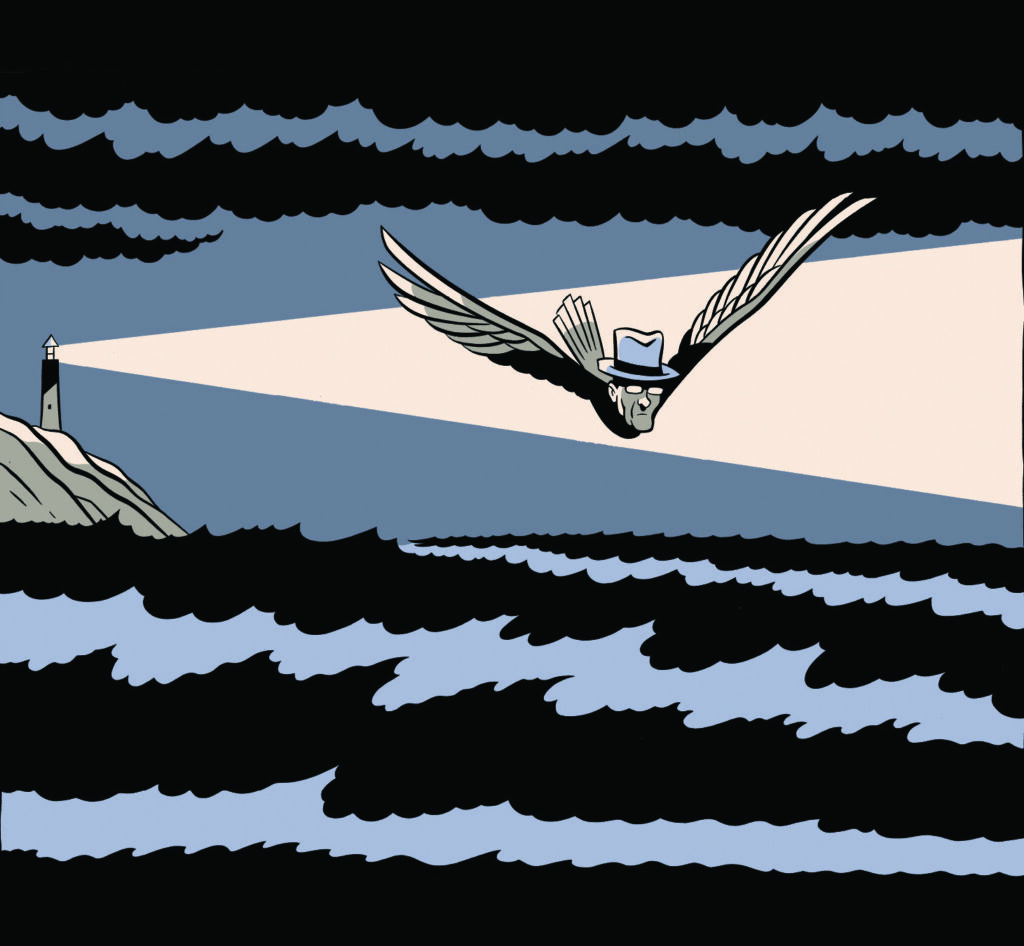

Simon’s fascination with the past and his unsuccessful attempts to freeze it in place also emerge in his obsession with novelty postcards from the turn of the twentieth century — the kind that feature larger-than-life produce and livestock, accompanied by homespun, understated slogans like “How We Grow ’Em.” What is important about these cards isn’t so much their novelty as their crystallized evocation of what appears to be a simpler, and perhaps more manageable, time. During his epiphany, Simon finds himself leaving his body to float through spaces that belong, undoubtedly, to the past: an abandoned factory, a wrecked and rotting home, a long-neglected orchard. Presenting the story in a kind of visual essay, without the interruption of human figure or dialogue, Seth takes the reader on the same journey as Simon. This vision offers a sombre counterpart to the cheerful postcards, reminding the reader that nothing ever really stands still.

Eventually, we come to understand that Dominion is also significant for Simon’s brother, Abe, because it is where he had a life-altering affair with a married woman whom he still believes he loves. Rendered in a drab mid-century style resembling the look of many northern Ontario manufacturing communities, the small town becomes a symbol of everything the brothers have lost through their relentless focus on the declining Clyde Fans business (and Simon’s trivial busywork). Labour — and what it can and cannot provide to the self in the face of human decay — is a major theme in the novel. Simon expresses a desire to “live forever in a single frozen moment” and worries constantly about the degradation of his mental and physical faculties, wondering decades later if he remains the same person as the Simon who experienced his consolatory epiphany. (It must also be said that Simon resembles a slightly older, more pensive version of Seth himself, especially as illustrated in his breakout mock-autobiographical graphic novel, It’s a Good Life, If You Don’t Weaken). These thematic concerns are brought into even greater relief as we witness Abe, following Simon’s death, wandering through the ephemera of Simon’s crumbling apartment, sliding into a suddenly contemplative life perusing only his memories and his brother’s old postcards and books.

How can we hold on to people and places that we are fated to lose? Clyde Fans is an ambitious work that doubles down on this problem, finding focus in the moments of stillness and reverie that each brother finds himself drawn to. With the exception of poetry, there are few genres as well suited to the task as the graphic novel. Intriguingly, the moments of reverie start to resemble the comic panels themselves, in a medium that produces only the illusion of movement, freezing the scene one image at a time. They also resemble the “real” Dominion, which has attained corporeal form via a meticulously constructed papercraft city that Seth has exhibited in various galleries since 2005. Surveyed from above, as it so often is when represented in the book, the town appears as a place of refuge for a lost way of life. Ultimately, Clyde Fans achieves the rare combination of confronting human mortality while simultaneously offering comfort: it provides a necessary antidote to human enterprise, doomed always to collapse into dust.

André Babyn studies medieval literature at the University of Toronto. His debut novel, Evie of the Deepthorn, comes out next year.