When an adult moves permanently to a second language, writes the French psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva in Strangers to Ourselves, their younger self becomes a nocturnal memory of the new body: a separate entity, an inner handicapped child languishing unused. If all of our psychic development has taken place in one language — the parental and societal prohibitions, the original mapping of one’s body, the nursery rhymes, the early desires, all that we have been before we transferred to a different language, in which we competently and elaborately live today — there will be disturbance. This awkwardness in the psyche, Kristeva argues, can turn into symptoms if ignored, and it’s recommended that bilingual adults find a way to translate the old self into the present. Writing, like art, is one way to do it; undergoing psychoanalysis in the new language is another.

It seems to me that Aleksandar Hemon, the prolific, award-winning Bosnian American writer who switched to English in his twenties, decided that his new book was going to be such a translation. My Parents / This Does Not Belong to You is two books in one, independent yet covering much of the same ground, to be read in any order. This Does Not Belong to You, in particular, seems to be doing the job of that kind of translation: a collection of memories, in which brevity and blank spaces (and the odd didactic intrusion) interrupt the swelling of emotion at just the right places. In This Does Not Belong to You, Hemon the narrator makes himself vulnerable in a new way. This is the work’s greatest thrill.

Hemon’s first book, The Question of Bruno, published in 2001, brims with intertextuality and historical and pseudohistorical referencing. His 2002 novel, Nowhere Man, tells of the travails of his somewhat alter ego, Pronek, in a fairly traditional, robust American storytelling way. The Lazarus Project is fiction and autofiction on multiple tracks — history and personal history — and it’s a deeply felt book with enormous, Dostoevskian pity toward an eighteen-year-old Jewish immigrant murdered by the Chicago police, in 1908; but the prose is still very butch, often angry, as it is in Love and Obstacles, another collection of short fiction. Males dominate most of those stories — women in Hemon’s fiction, when they appear, are minor characters, not infrequently of sexual interest — but the narratives shine a questioning light on men’s behaviour, their delusions and self-mythologizing, and man-to-man violence.

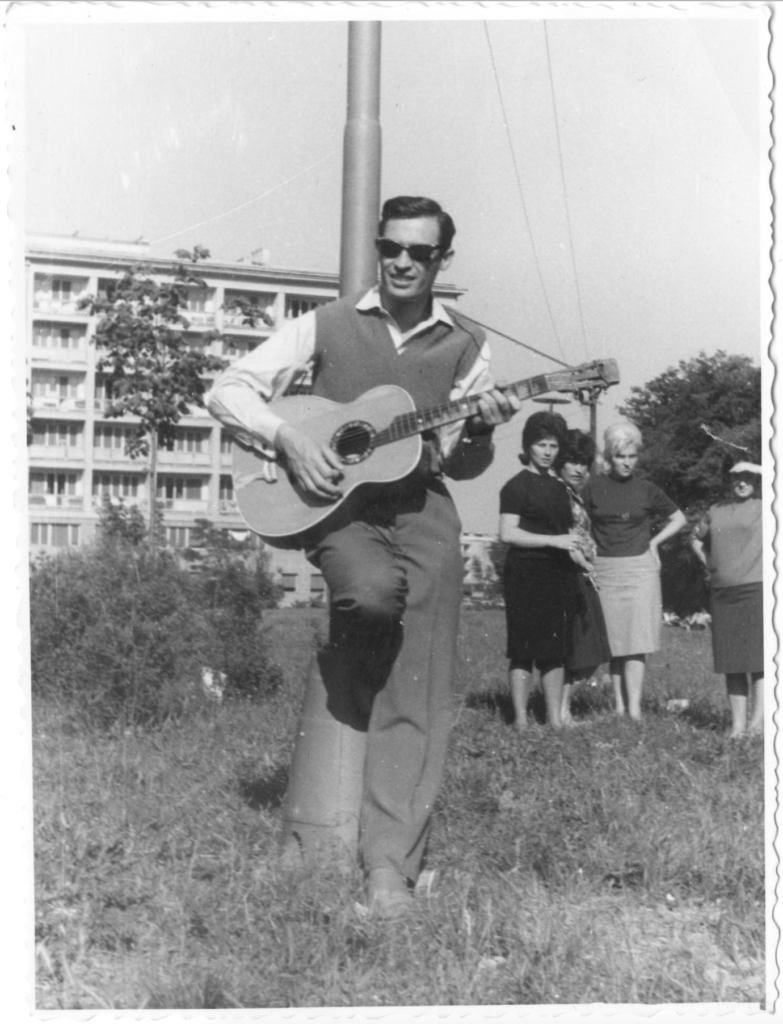

Distant, gently comic glimpses of one’s own parents.

Aleksandar Hemon

With The Book of My Lives, an essay collection from 2013, one finds the stomping grounds of another recognizable Hemonian persona: the preternaturally cool narrator who’s a devoted Americanophile by adolescence, listening to all the right bands and refusing to buy into Yugoslav socialism’s grey earnestness. Many of the entries, like much of Hemon, are admirably well written and have the smoothness and easy page-turning of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet, but Hemon the essayist is inexact and unsubtle on detail and context on anything that’s not either Bosnia or the United States. (For a much better analysis of Njegoš and Montenegrin cultures than Hemon’s, see, for example, Mark Thompson’s biography of Danilo Kiš, Birth Certificate.)

Hemon’s most recent novel, The Making of Zombie Wars, is the only one of his books I’ve abandoned. There is just too much knowingness in it, with its exacerbated mimeticism of genre and winking. My Parents / This Does Not Belong to You could not be more different — and it delicately changes the lighting on Hemon’s entire opus.

The part titled My Parents, the biography of a couple, is a thing apart from the open vulnerability of the other half, This Does Not Belong to You, a memoir. Though we have met the characters of Dad (Tata) and Mom (Mama) in some of Hemon’s earlier works, My Parents is wholly their territory. It follows the couple’s childhoods, youth, and married and working lives until the fall of Yugoslavia and the start of the Bosnian War; it continues with their immigration to Canada and efforts to rebuild their lives in Hamilton and the Greater Toronto Area. (Hemon himself visited Chicago in 1992 and got stranded after the siege of Sarajevo started. He stayed and became a U.S. citizen.) The trajectory of the older Hemons has been fairly lucky, as refugee trajectories go: in Hamilton, they live in a house that they own, and they have a critical mass of the paternal side of the Hemon family around them, while they also keep ties with Bosnia and return to their Sarajevo apartment annually. Yet this trajectory has also been hard: emigrating in your teens or twenties is very different from emigrating in your fifties and sixties, and losing a country as a young person is unlike losing one later in life. From their new home in Ontario’s steel town, and with very little English between them, the Hemons have had to reimagine themselves as Canadians.

My Parents documents how the Hemons managed to grow enough new roots in this cold land to make for a good life. It also shows where their adjustments have failed (Hemon does this astutely in sections about anxieties and habits around food). Overall, it is a tribute that documents a step-by-step progression toward making a home — filling one’s life with meaningful activities, then filling it again when displaced across the ocean. Hemon’s father, in particular, has found a way to live a busy, productive life, filled with beekeeping, vegetable gardening, and DIY projects (he is good at making things and has built his own shed). There is much less about Hemon’s mother, and in the last third of My Parents, while describing the gendered division of labour in his parents’ marriage, Hemon spends some time analyzing why this is the case. In Yugoslavia, both parents worked outside the home, but Tata was free to roam the world and create stories, while Mama, the writer argues, was always closer to home and taking care of the children. This narrative asymmetry continues in Canada, where the paternal side, with its family gatherings and singing, takes over completely.

The tone of My Parents is slightly distant, pseudodocumentaristic, and, on occasion, gently comic, with the cool Hemon narrator popping in here and there (“I was a natural, cacophonous anarchist, my ideological guidelines provided by the guitars of the Clash and the Jam and Gang of Four”). But as you flip the book around and start reading This Does Not Belong to You, you find yourself on an altogether different plane. A peculiar world emerges from those snapshots in prose, familiar but heightened: a Balkan childhood where violence is an accepted currency, especially among boys and their gaggles, but also from adult men toward children in need of disciplining, from boys to girls, girls to girls (I can attest to this, if Hemon couldn’t), boys to small animals, boys to breakable objects. And the narrator, looking back at it all from 2019 and putting it under the light of the English language, is retelling this normalization of cruelty in a quiet and succinct way, which makes it all the more devastating.

“Ako smo pali bili smo padu skloni” (If we fell, we were inclined to fall) was one of the most quoted verses in Yugoslav cultural conversations after it first appeared in a 1957 collection by the prominent Yugoslav modernist poet Branko Miljković. Looking back on the fate of Yugoslavia, some of us keep wondering if we worked toward our own doom, unknowingly, in the years preceding war. How did we let this happen to us, what actions built this up? How did we make ourselves so prone to falling? This Does Not Belong to You is agnostic on the possible connection between the naturalized violence in Balkan male childhoods and the ease with which violence took over the Yugoslav public sphere and tore the country apart. But the questions linger. Here the episode in which private violence and historical violence rub shoulders most closely is when Hemon, as a boy, throws a rock and cracks the glass on a shop window, just because he could get away with it undetected. “Many years later,” the narrator comments, “during the siege, the building across the street was subject to a rocket attack, in the course of which all of its windows, including Špedicija’s, were blown out.”

This Does Not Belong to You documents the stellar moments, too: first dates, first kisses, first successful impersonations of Jerry Lewis, first life-changing LPs. All of that past life is gone for the American Hemon, however; the people who populate the stories are either dead or in an inner or actual exile.

The two texts sit uneasily next to each other as one book, with no synthesis to bridge them. But My Parents could serve as an excellent rejoinder to parts of its companion text. “It occurred to me just yesterday that I’d been wrong about everything,” Hemon writes in one of the melancholy fragments of This Does Not Belong to You, “entirely wrong from the very beginning, though I can’t tell what the actual beginning might have been, and of what. . . . At some indeterminate moment deeply buried in my nebulous past, I deemed a false proposition as true and made the incorrect decision.” This I am familiar with: it’s the adult immigrant’s version of “Once in a Lifetime” by the Talking Heads: “You may ask yourself, Well, how did I get here?” Why this alternative life and not any number of others?

There is at least one certainty, however, that the author should enjoy: with this book, even in a different language, he has done right by his mother and father. Though Hemon and his parents ended up in different countries, he has remained present in their lives, keeps them involved in his, and honours them through his work. It’s more than a lot of us immigrants to this far continent manage to do. Hemon should be proud; and we who never managed to put in order our relationship with our parents before they were gone will enjoy this feat vicariously.

Lydia Perovic moved from Montenegro to Canada in 1999. Her novella, All That Sang, is about a French orchestra conductor.