Though he loomed large in my life, my father was difficult to know. He kept to himself, and he liked it that way. He was solitary and solemn. A storer of secrets.

One story he did share was that of his high school friendship with Mordecai Richler. The claim of their closeness always intrigued me. My father, Marvin, was not the least bit literary, and surely being an ally of Richler’s — even before he was known to the wider world as Quebec’s most opinionated and controversial writer — required an appreciation for the written word? At least that’s what I thought when my own interest in literature was developing. That interest, and my father’s past connection, led me to Richler’s work.

For a Jewish adolescent growing up in suburban Montreal, Richler, who had transformed the rough neighbourhood around St. Urbain Street into a vital and authentic setting for fiction, was a natural choice. His novels transported me to a past that had also belonged to my father and a setting that had shaped his world. Like his buddy Mordy, my father had known the hardscrabble day-to-day life of the Main, as St. Lawrence Boulevard was known. Unlike Mordy, who was president of his graduating class at Baron Byng High School, my father wasn’t book smart. What he did have was a head for business, and he put it to use. It was his ticket out of poverty and the unsightly walk-ups and cramped cold-water flats of his childhood. At eighteen, he entered the clothing import business, where he made enough money to leave the Main and eventually purchase a home in a new subdivision — a place of his own in uncharted terrain.

In 1960, my parents moved out of their small apartment in Snowdon and purchased an affordable bungalow in Chomedey, a bedroom community with a growing Jewish population located eighteen kilometres north of Montreal on the island of Laval. So when I say I’m from Montreal — which I do whenever someone asks about my roots — I’m lying, but just a little.

Throughout my childhood, Chomedey was a bleak place that offered few amenities. Along Labelle Boulevard, the main thoroughfare, were a number of eateries: the Dragon Room for Chinese food, Mama Bear’s for fried chicken, a local pizzeria, and a Dairy Queen. There were two supermarkets: Steinberg’s, where my mother shopped weekly, and Dominion. The one strip mall had a Woolworth’s, where shoplifting was effortless. I may have been a reader, but I was also daring.

For fun, we had La Récréathèque, which opened in 1968, at the otherwise desolate intersection of Labelle and Notre Dame. The Rec, as it was called, housed billiard tables, bowling alleys, and indoor tennis courts, but its main attraction was indoor roller skating. Adjacent to the Rec was a McDonald’s, where I lounged for hours with my closest friend, Audrey, and mastered the art of drinking coffee, however unlikely that may seem in today’s highbrow espresso culture. On Elizabeth Street, Kennedy Park had a small-scale castle; it was designed for children but became a popular site for adolescent trysts.

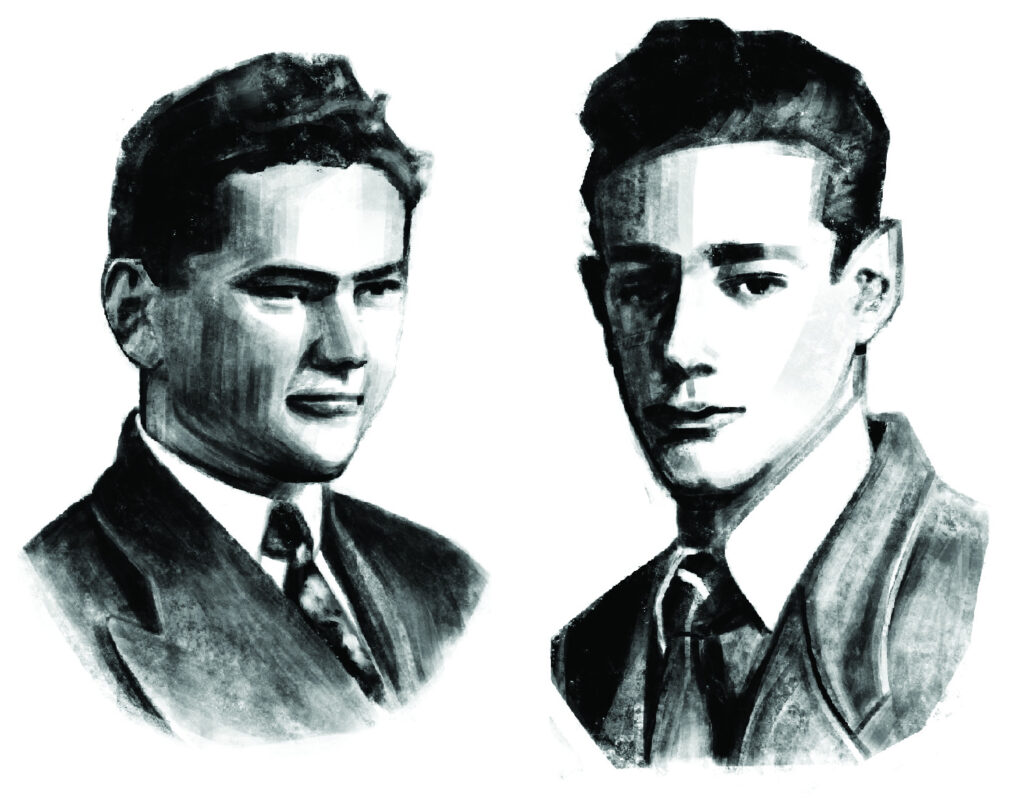

The young friend. The young writer.

Stefanie Wong

Public transportation didn’t exist. As a teenager, I would hitchhike over the Cartierville Bridge and onto the island of Montreal, heading for the amusement rides of Cartierville’s Belmont Park. Freedom, at last — that is, until I escaped a close call with one particularly grabby driver.

Earlier, however, I had found a much safer and more enticing escape through books. By chance, at my school library, I discovered Sydney Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind Family series and devoured each title. They were about a Jewish family, which included five school-aged girls living in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As the eldest of three daughters being raised in a Jewish household, though a far less observant one, I saw myself reflected in Taylor’s series. For a while, I was satisfied.

But my inheritance was St. Urbain and the Main, not New York, and as I moved into adolescence and began searching for a more faithful image of myself in literature, I turned to Richler. Perhaps he could provide what I was looking for: a more authentic depiction of my own family dynamics, which included disharmony and sibling discord, and of characters like me, a far less agreeable girl than any of the five pictured by Taylor.

My father, though an early riser, cannot start his day, will not get out of bed, without first lighting up. Upon waking, before even visiting the bathroom, he perches on the side of the bed and plants his feet on the carpeted floor. Facing the window and looking out at the mounds of filthy snow piled high and blocking our driveway, he reaches for his package of Export As. A strong brand, the cigarettes are always close at hand. He pulls one out and lights up. Deep inhale, another deep inhale, and slowly he leaves the dark dream world. To enter the day takes energy and decision, which he cannot muster without his morning cigarette — the first of a two-pack-a-day habit that will nearly kill him at age fifty. In hospital, recovering from his first heart attack, he makes the decision to quit, but that is in the future. For now, he knows his way forward and into the day: sit up, light up, and light out.

I could only ever guess what was in my father’s head. He spoke little and was uninvolved in day-to-day family life. Each morning, to avoid traffic, he left early for his office on St. Lawrence Boulevard. In the evenings, he listened to the news on CJAD and read the Montreal Star; when it folded in 1979, he turned grudgingly to the lesser Gazette. On weekends, it was the New York Times. Regularly, he sat glued to the television watching the Montreal Expos, cheering on Rusty Staub and shouting “Go, go, go!” at every home run. Baseball was his passion, and sometimes he and my mother would catch a game at Jarry Park. He worked a lot but appeared to dislike what he did, always coming home depleted and uninterested in the evening meal (despite my mother’s excellent cooking) or the lives of his daughters. When he did take notice of us, it was to show disapproval of our noisy chatter and our girlishness, which he scorned with a look of reproach that said, “You are frivolous.”

My bedroom in that late 1950s Chomedey bungalow was a refuge, small but jam-packed with white furnishings, trimmed in gold. It had flower power wallpaper — bold blooms in vibrant pink, red, and yellow — and a red floral bedspread topped with pink woolly throw pillows and the red shag carpet. I had chosen the decor myself, and my mother had gone along with my vision. It was there that I read first Nancy Drew and then Agatha Christie, crafted handmade books out of cardboard and construction paper, wrote in my diary about the trials of first love and devastating betrayal, listened to Cat Stevens. It was where I started writing poems, angst-ridden ballads, one of which, stirringly titled “The Doings of Dope,” I proudly published in the 1974 Chomedey Polyvalent yearbook.

It was also there, in my bedroom sanctuary, that I read Richler’s novel Son of a Smaller Hero, published in 1955. It came highly recommended by my high school English teacher, who grasped its relevance. She was right.

Son of a Smaller Hero showed me the grim streets of the city, my father’s Montreal. In tracing the geography of Richler’s childhood and youth, this early novel gave me a vivid sense of my father’s own formative environment, with its people, its culture, its grievances. Richler also revealed just how “caged” — a word he repeats in the novel for emphasis — both he and my father must have felt by the circumstances of their young lives. Here, I could enter my father’s unvoiced history.

What I found most thrilling, though, was Richler’s use of my surname. In the novel, Samuel Panofsky, an important character, owns a lunch counter and soda fountain modelled on the actual Wilensky’s. (Today, it thrives as Wilensky’s Light Lunch on Fairmount Avenue.) That Sam is a Communist — like the true founder Moe Wilensky — makes him no relation to my father, but the description of his “big pleading eyes,” which are “grey” and “melancholy,” could not have been more apt.

Sam Panofsky is a soft touch, supportive of his sons, Aaron and Karl. He is also especially kind to Noah Adler, the novel’s protagonist, for whom Panofsky becomes a surrogate father figure. As Noah tells him, “There is not one boy in the neighbourhood who doesn’t remember you, Mr. Panofsky. Whenever we were in trouble we came to you.” When Noah is in need, Panofsky lends him money and a listening ear. Unlike Noah’s parents, Panofsky believes that Noah will find his way in life, even as he rejects his Jewish upbringing. At the funeral for the patriarch Melech Adler, Noah’s stern and stony-hearted grandfather, Sam’s younger son, Karl, is a pallbearer.

The father I knew was nothing like Richler’s character. Aside from his eyes, Sam bears no resemblance to the actual Panofsky whose surname he shares. But if my father himself was not brought to life by Son of a Smaller Hero, the world in which he was born and raised and experienced the trials of adolescence certainly was illuminated. I perceived the pathways, both public and private, of his early years. Moreover, Noah’s realization, at the end of the novel, that Sam Panofsky will “never quit” his post on City Hall Street affirmed the bond between Richler and my father, who grew up on that very street.

Richler’s borrowing of the surname Panofsky was evidence of my father’s avowal of friendship. And even as I resisted asking my father if the novel rang true to his experience, I knew that I was hooked.

MacKinnon sneers that Monday morning when, as a student, my father asks about his grade on the previous week’s math exam. “Panowski, can I give you less than zero?” What arrogance, what condescension, and what humiliation. The student turns his back on the teacher and regains his desk in the back row of Room 41, a plan slowly forming in his mind.

He sits through the algebra lesson, but he’s not listening. In the farthest reaches of the classroom, he’s preoccupied with something far more important. He knows he needs help, and he needs it fast.

Finally, the students disperse for lunch. Freed from the constraints of his desk, facing a teacher who loves his subject but loathes his students, he springs into action. Quickly, he summons Stan, Phil, and Hymie. Mordy has already raced to his side, sensing his buddy’s rising excitement.

The boys case the halls: Anyone in sight? No, the coast is clear. All the teachers have slipped away. Over lunch, in the privacy of Baron Byng’s staff room, they bemoan the failings of their Jewish students, their impudence and odious ways. They don’t know the half of it.

The rusted window of the 1920s classroom — heavy and challenging — is hoisted open. It’s not as weighty, however, as the teacher’s mammoth-sized desk. That’s a job for five young men incited by hatred and a need for vengeance. They rise to the task, urgently propping, lifting, and finally catapulting the desk out the window, where it falls two storeys onto the concrete and shatters, with a resounding crash that feeds the souls of impoverished boys. They are all on fire, but none more than Marv and Mordy, “cronies and . . . chips off the same block,” as Richler styles them at the time, in a story fragment written when he was still a student.

I escaped the way middle-class white kids usually do, by going to university out of town. My parents and their friends could not understand my decision. Why choose to leave home when you could so easily attend McGill or Concordia, they reasoned. But I yearned to quit Chomedey in the same way my father had needed to flee the Main. I could no longer bear the isolated, insular, suffocating place. I needed a way out and found one in Carleton.

For all of university’s excitement, it was also a time of sadness. Having finally abandoned the desolate suburbs, a place I professed to despise, I felt unmoored. Instead of release, I experienced an acute, though unexplainable, sense of loss.

In second year, I read The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, published in 1959 to great acclaim. Even as an undergraduate, I could see that this was a much stronger and more mature novel than Son of a Smaller Hero. I loved it for its intimate and daring depiction of Jewish Montreal. I also recognized Duddy and his abrasive arrogance — the brashness that led him to mistreat Yvette and Virgil, two Gentile characters who fall under his spell and whom he exploits for the services they offer. In greedy, grasping Duddy Kravitz, I found a fully realized character no longer burdened, as Noah Adler had been, by the author’s own anxieties.

I also noted then that Richler struggled to draw female characters, who were so much less convincing and more vulnerable to stereotype than any of his many male figures. Richler’s view of women — much like my father’s — was “very old-fashioned,” as the writer conceded publicly in fall 1990, in conversation with his son Daniel, then host of TVO’s long-running book show, Imprint. No matter. Richler provided so much of what I had been hoping to find in literature — my past, my place, and, increasingly, my parent — that I willingly overlooked the perceived weakness.

So I did regret the meagre showing of the surname Panofsky in Duddy Kravitz. Having been treated to three characters named Panofsky in Son of a Smaller Hero, one of whom is an ally to the protagonist and central to the novel’s action, I found in Duddy only a single stark line: “‘White men,’ Panofsky said sourly.” Imagine my frustration. That the gruff comment was true to my father’s darker side as a steely businessman did not make up for the disappointment I felt. Here I was, hoping for more of Panofsky, but I could locate no more than two words uttered by an embittered cameo part.

It has taken time and reflection, but I no longer feel let down by Duddy Kravitz. Today, I am grateful for that one line, which I take as further evidence that Richler was attached enough to my father that he was compelled to drop Panofsky into a scene and simply leave him there, undeveloped. And whenever I teach this most popular of Richler’s novels to my own undergraduate students, I never miss a chance to point out my last name in the text. It’s my claim to fame, I always joke, and together we laugh.

Twice a year, for six weeks at a time, my father travels to Asia on business. As a clothing wholesaler, he purchases inexpensive children’s apparel produced in Hong Kong, Korea, and Japan and ships it to Montreal for national distribution. Following each trip, when the containers finally arrive, he patrols the city’s port, worried about vandals and thieves.

Alone in Chomedey, my mother dwells more on the distractions on offer in Japan, especially the alluring geisha. She knows a lot can happen in six weeks, yet my father always returns to us and brings cherished gifts: black-lacquered jewellery boxes inlaid with mother-of-pearl, gold ID bracelets engraved with each daughter’s name, sapphire pendants and rings for my mother. He doesn’t explain what he does when he is away — and, truthfully, I don’t really mark his absence — but I am happy at every homecoming. And my mother’s relief is palpable.

When I next came across the surname, in The Incomparable Atuk, from 1963, I was amused. In Richler’s black comedy, a key character known only as Panofsky is described as a “tubby, middle-aged” father to his daughter Goldie and sons Leo and Rory, the latter successful enough to have anglicized his surname to Peel. Pro-American and virulently anti-Gentile, Panofsky is a graduate student in sociology whose thesis focuses “on heredity and environment in Protestant society.” He hypothesizes that white Anglo-Saxon Protestants share the same facial features — a “no‑face” with “turned-up nose and . . . pasty complexion” — and are indistinguishable from one another. As part of his research, and to prove his absurdist point, he and Leo go so far as to surreptitiously switch ID bracelets on babies in the maternity ward of the fictitious Protestant Temperance Hospital. Panofsky believes that the crime will go unnoticed by parents, and he is right.

That the father-and-son duo are never brought to justice could be construed as their creator’s backhanded endorsement of an inane view and hare-brained scheme. Here, however, I must insist that tubbiness is the only true-to-life attribute in this particular characterization of Panofsky.

My grade 5 teacher writes home: “Ruth cannot read the blackboard. Please have her eyesight checked.” Although I have mentioned my weakening vision, my parents have brushed off these complaints. “No one in the family,” my mother says, “wore glasses at your age.”

But the note from my teacher prompts my father to act. He decides I should see Shulem Friedman, a former Baron Byng classmate who is now an ophthalmologist. Dr. Friedman examines my eyes and concludes that I do, indeed, require glasses. I am relieved, but also concerned that they might not be seen as fashionable among the preteen set. “Don’t worry,” he reassures me, “when you’re sixteen, your father is going to buy you contact lenses.”

I am startled and grateful for this show of kindness, so unfamiliar.

One Friday, my father visits me in Ottawa. He has business in the city, and we arrange to have lunch. It is a strange and alarming thing to contemplate, me being alone with my father. We have never spent time together over a meal in a restaurant, conversing, just the two us. What will we talk about, I wonder. That we both know devotion, he to baseball and me to books?

He drives in from Montreal, spends the morning in meetings, and then calls for me at my low-rent apartment on sketchy Bell Street. We make small talk en route to the ByWard Market. I so want to relax into easy dialogue, to connect with my father, but we have no past connection to draw on. And he intimidates me. Yet I see this as a chance that may not come again. And so, midway through lunch, I somehow muster my courage and dare suggest that he might open up more. He shakes his head, lowers his gaze. “Do you actually expect me to change now,” he asks, “when I’m nearing sixty?” “No, I guess not,” I answer sullenly. And it’s true, I don’t. I bite into my sandwich, swallowing regret and the last of my hope.

The name recedes from view. The 1969 short story collection The Street and the major novels St. Urbain’s Horseman (1971), Joshua Then and Now (1980), and Solomon Gursky Was Here (1989) do not feature characters named Panofsky. Richler still mines the past for his fiction but chooses other surnames for his protagonists: Hersh, Shapiro, Berger, Gursky. Though I am unsatisfied, I understand. After all, Richler and my father had shared a long-past adolescence, and their lives had since taken different paths. Perhaps Richler had lost his liking for the name Panofsky? Perhaps his friendship with my father had been relegated to memory? I could not have known that Richler would come through for me in the end, and with such vigour that never again would I question his link to my father.

My own life soon led me, like so many others, to Toronto, where I married, completed graduate school, had my first child. Richler, meanwhile, often lamented and lampooned this generational exodus in his fiction and journalism.

The birth of my son brought my father such joy that he could not help but express powerful feelings of happiness. His blue-grey eyes lost their sadness, and his face glowed as the two played together with plush toys, miniature trains and cars. Later, they walked hand in hand to the playground, lured by the swings. It had always been my father’s wish to have a boy, a desire conveyed less through words than by a poignant sense of having missed out on what is most important in life. I was pleased to be his redeemer in a sense, the deliverer of so enrapturing a grandson. But my father’s immediate and fervent attachment to my son brought home the truth: it would have been so much easier had I been born a boy.

It’s mid-December, and we’re together as a family, navigating Interstate 95 through Georgia, with its live oak trees that appear haunted by ghosts, whose wispy limbs reach down toward the ground. Three girls cram into the back seat of my father’s blue Buick LeSabre. This year, we’re even joined by my long-widowed grandfather. My father is the only driver for three straight days. (Only years later will he reluctantly teach my mother how to drive.)

It’s the final morning of a gruelling trip to Florida, where we always spend two weeks during the annual Christmas break. We’ve just crossed the state border: “Welcome to Florida — The Sunshine State,” a sign proclaims. We clamber out and enter the visitor centre. We all need to pee but aim first for the complimentary glass of freshly squeezed orange juice. We gulp it down, then spy the succulent grapefruit on display. We bring the tantalizing orbs up to our noses, breath in the crisp citrusy scent.

As soon as we cross into Florida, the gloom that never fails to descend by the end of our first day on the road invariably lifts. We still have one full day’s drive south, down to Fort Lauderdale or Miami, wherever my parents have secured reasonably priced hotel rooms. But as we return to the car and my tone-deaf father puts the key into the ignition, he breaks out into song: “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary.” He’s off-key, of course, but it doesn’t matter. Whenever he sings his favourite First World War tune, I see my father as he once was: a young man, who knew camaraderie and rejoiced in freedom.

I come to accept the long hiatus in Richler’s use of Panofsky and relish each new novel for its distinctive narrative voice, which seems to deepen and grow richer over time. Richler becomes my go-to author. I turn to him whenever I need a jolt, a literary return to a Jewish sensibility informed by a love for Montreal as a vital, beautiful city where Jews and Gentiles, English and French live side by side in persistent but familiar conflict, at once comforting and irreconcilable. His work lifts me out of the busyness of life — teaching, writing, raising a family. A homecoming, it offers me unmatched authenticity. I trust Richler.

Eventually, my trust pays off. In September 1997, Richler publishes Barney’s Version. It appears just before my father dies in December of a second heart attack at age sixty-six. It is to be Richler’s closing novel, for he also dies too soon, just four years after launching his grand triumph.

I like to think that Richler had purposely reserved the name Panofsky, sensing he might need it for a protagonist whose personality would emerge as more complex and emotionally nuanced than any other in his impressive oeuvre. And, indeed, Barney Panofsky, the force at the heart of Barney’s Version, is Richler’s consummate character. On first reading the novel, I am stunned that Richler has given Barney my father’s surname, but I am also charmed. Barney, I see immediately, is poised to become one of literature’s great figures. My gratitude to Richler for having created the voice of Barney Panofsky is profound.

Some may dispute my claim, but I believe Barney and my father clearly resemble one another. First, their given names: Barney, Marvin — the syllabic echo is unmistakable. Second, their natures: a tough demeanour obscuring a softer interior kept well hidden from view. Third, their livelihoods. Barney describes himself as “an exporter,” a euphemism for his various undertakings. He exports French cheeses, Italian Vespas, and bolts of Scottish cloth. He traffics in stolen ancient Egyptian artifacts. He produces schlocky Canadian television. My father is in the shmatte trade, selling ready-to-wear clothing to Woolco and Zellers. As Barney’s first wife, Clara, insists, “Panofsky. Sounds like . . . the owner of a clothing store. Everything wholesale.”

Fourth, their tastes. Both are brand devotees — Barney to Montecristo cigars, my father to Export A cigarettes. Both enjoy the same heimish foods — “smoked meat, salami, chopped liver, potato salad, sour pickles, bagels, and sliced kimmel bread.” And when my father drinks, only on Passover, he prefers whisky, like Barney.

And, finally, their offspring. Both have three children who depart Montreal, one of whom is a writer. For my father, I am the writer. For Barney, the writer is his son Saul, whose name has real-life resonance. Saul is my father’s kid brother and only sibling, ten years his junior. It is my beloved Uncle Saul, in fact, who is the bookish one in the family. An avid reader, he helps cultivates my own taste in books and introduces me to E. Nesbit, Rudyard Kipling, C. S. Lewis, and David Walker, whose novel Geordie, from 1950, becomes a favourite. Later, he shares his vast library with me.

I finished reading Barney’s Version for the first time and knew instantly that I had to review it. And I had already written the last line, if only in my head. I contacted the books editor at the Toronto Star and explained the importance of my surname to the novel. Happily, he agreed to let me review it, and I was thankful for the chance to publicly proclaim my father’s ties to the famous novelist, whose work I had long admired.

The half-page review was published on my birthday, which I regarded as auspicious. Today, its opening reads as if to portend this very essay:

My father insists that he and Mordecai Richler were high school chums. Although I secretly doubt the closeness of their friendship, I use their connection to my advantage, especially when teaching The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz.

Thankfully, I was able to share the review with my father, who died soon after he saw it in print. I also sent Richler a copy via his publisher. I did not expect a response, even though I had concluded the review — rather comically, I thought — by thanking him for giving his lead character my father’s surname, which I hoped never to have to awkwardly spell out again: it’s p as in Peter, n as in Norman, f as in Frank, and so on.

But Richler did write back, thanking me for the review and confirming that my father “was indeed a high school pal of mine and I last saw him at a Baron Byng High School reunion.” Proof at last!

Richler reinforced the connection when we finally met in person in November 1999. At the time, he was living in Toronto and was a distinguished visiting associate at Trinity College. As I made my way across the University of Toronto campus to Massey College, where he had an office, I knew that Richler was willing to meet with me — to generously carve out time and put aside his writing — only because of his link to my father. That was reason enough for me.

I was embarking on a book about Adele Wiseman’s literary career at the time. Richler had known her in London, where both novelists lived in the 1950s. We chatted, first about Wiseman. He offered his memories of her, and then asked pointedly if I thought my book would have a market — momentarily revealing his legendary crustiness. Eventually, Richler asked about my father; I had hesitated to raise the subject of their friendship myself. He absorbed the details I offered, impossible though it was to provide a full picture of the man my father had become after leaving the Main. A decade later, I would learn through Charles Foran’s biography that Richler’s next novel, which existed in outline at the time of his death, was conceived with a character named Marv.

I had brought along my copy of Barney’s Version to Massey College, and before we parted, I asked Richler if he would inscribe it for me. “For Ruth Panofsky,” he wrote tersely but kindly, “with all best wishes, Mordecai Richler.” At last, the joining of names, in Richler’s own hand.

A new clarity came from that meeting. What I had been searching for‚ a key to my elusive and distant father, I could not find in Richler’s novels. But Richler had given me access to my dad’s world, a world bequeathed to me. That, I could see with sudden sharpness, was my personal legacy.

Meeting Richler also boosted my pride in being a Panofsky, a surname so fertile for the writer that he used it often and made it his own, in the end turning it less into fiction than into poetry. For as Barney himself proclaims, in reference to his own dad, the much-loved and irreverently loquacious Detective-Inspector Izzy, “Poetry comes naturally to the Panofskys.”

Ruth Panofsky teaches English literature at Toronto Metropolitan University. She recently received the Royal Society of Canada’s Lorne Pierce Medal.