Before the pandemic, before isolation, and before the suspension of all major sporting events, coaches were going through a reckoning. The increased empowerment of player associations, the use of social media as an accountability mechanism, and the changing expectations of what constitutes safe, fair treatment of athletes have all illuminated systemic problems in sport. Many widely accepted standards and expectations of yesterday just no longer apply. And this shift has been felt sharply in professional hockey.

In late 2019, Bill Peters of the Calgary Flames, Mike Babcock of the Toronto Maple Leafs, and Marc Crawford of the Chicago Blackhawks were all relieved of their coaching duties or publicly reprimanded, dogged by allegations of bullying, physical abuse, or personal misconduct. And in November, Don Cherry, the Jack Adams Award–winning coach and long-time, outspoken fixture of Hockey Night in Canada, was fired for making controversial on‑air comments about immigrants. While these stories are not unique, they signal a pivotal moment, when politically incorrect commentary or behaviour that may once have been chalked up to tough love is now deemed offensive. We have long admired coaches in spite of harsh, antagonistic behaviour, sometimes even crediting their success to it. So who and what are coaches supposed to be, now that such conduct has been called into question? Are we to continue celebrating them as chief motivators and builders of good character rolled into one? Indeed, certain sporting clichés appear increasingly outmoded.

It’s within this context that Ken Dryden’s Scotty: A Hockey Life like No Other offers an alternative perspective on coaching. Scotty describes Scotty Bowman’s five-decade journey through the NHL, with nine Stanley Cups and a league-leading 1,244 NHL regulation wins along the way. As coach after coach is punished for behaviour that may have been acceptable yesterday, Bowman’s character remains largely unchallenged, even unknown. Dryden squares Bowman’s longevity and success with the fact that he never had the biggest personality in the room. What he did have was the most advanced vision of the game — of where it was going and how to adapt.

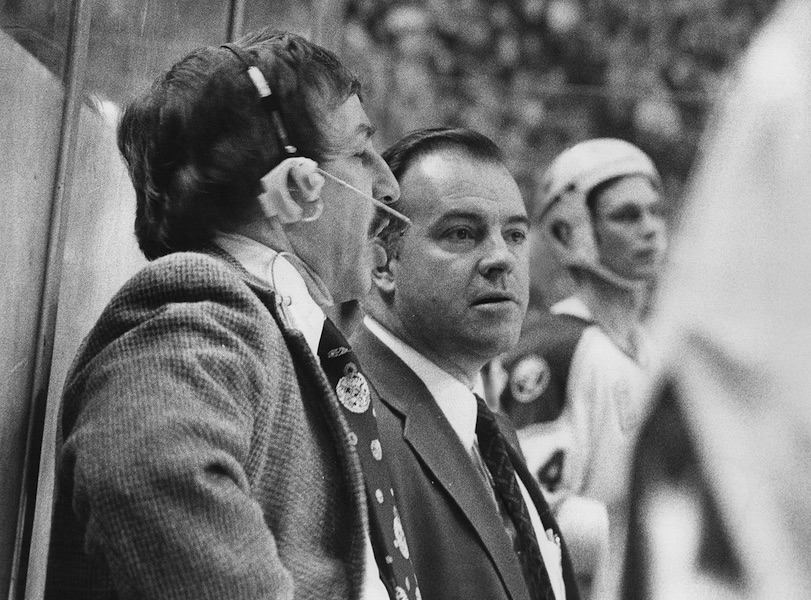

At the centre of things, a hockey great who blends in.

Frank Lennon, 1979; Toronto Star Archive; Toronto Public Library

Bowman, now eighty-six, was never gregarious as a coach; his strength was not in his personality or his ability to spin a yarn. There was no driving ideology or type of play that defined his style; he paid attention to larger developments and to the smaller details of individual games. “Scotty doesn’t pronounce,” Dryden, the former goaltender, writes. “Pronouncing would mean knowing something now and forever, and he doesn’t know anything forever, and doesn’t want to. He knows there are no timeless strategies.” If there were, he asks, “what would be the point of watching?”

Bowman’s defining strength — his quiet flexibility — limited his public profile relative to that of other accomplished peers. “Unlike Vince Lombardi and his growl, Red Auerbach and his cigar, Phil Jackson and his ‘guru’ persona,” Dryden explains, “Scotty blends in.”

Nearly forty years ago, when he wrote his first book, The Game, Dryden asked Bowman to describe a coach’s most important role. “To get the right players on the ice,” Bowman replied. To enthusiasts, then and now, this may sound like a tepid response, but it speaks directly to his approach: focus on the ice, adapt to your players, see where things are going rather than where they may have been.

Scotty Bowman didn’t need to be larger than life throughout his career, because the game already was. So why cooperate with an authorized biography? In 1998, the freelance sportswriter Douglas Hunter published Scotty Bowman: A Life in Hockey, which described a coach who played mind games and treated players harshly. Bowman declined to be interviewed for that one. Even with The Game, published in 1982, Dryden had trouble understanding Bowman the man: “I’m afraid that knowing him better, and having him know me better, things might change.” Even after countless hours of more recent interviews with Bowman, Dryden has not gotten much further on the personal level. Rather than fight Bowman’s introversion, he embraces his subject’s strengths, paying minimal attention to his life off the ice or his personal interactions with key players. (He does mention one conflict from the time he played for Bowman’s Canadiens, when Bowman confronted him about acting out after allowing goals, but relationships generally take a back seat.)

Instead of asking Bowman to philosophize on the game’s culture, Dryden assigns him a straightforward coach’s task. Together, the two hockey minds agree on the eight greatest teams of all time: the 1951–52 Detroit Red Wings, the 1955–56 Montreal Canadiens, the 1962–63 Toronto Maple Leafs, the 1976–77 Canadiens, the 1981–82 New York Islanders, the 1983–84 Edmonton Oilers, the 2001–02 Red Wings, and the 2014–15 Chicago Blackhawks. Bowman analyzes the picks and Dryden adds colour, connecting the dots between various players, franchises, and communities. Stretching from 1951 to 2015, the teams span sixty-four years of the sport — with Bowman having coached, advised, or closely followed each of them. The final chapters end with Bowman matching them in a fictional playoff series, ultimately picking Dryden’s own 1976–77 Canadiens as the greatest of all time. This offers a satisfying conclusion for the reader — and certainly for the author — as well as illuminating insight into what has changed about the game and what hasn’t.

Bowman is no storyteller, but Dryden thrives in that role, exploring the context in which the sport continually reinvents itself. The league’s expansion in 1967, its move to an open-entry draft, the rise and fall of the World Hockey Association, the shift to a more open and offensive game in the 1980s, and the emergence of European players — these have fundamentally helped shape the game. We see these developments against a backdrop of broader cultural and political change. The escalation and thawing of the Cold War, the emergence of Quebec separatism, and the expansion of air travel all materially impacted the league and the teams that Bowman coached. His durability through these changes was his greatest achievement and most compelling attribute.

Resilience in the face of change required thorough preparation, and Dryden depicts the most studious analyst of the game, always learning, assessing, and adjusting in real time. The league’s more recent changes include elimination of the two-line pass rule, a move to shorter shifts, and the use of advanced stats to assess value and predict future output. Bowman may have lacked the tools that statisticians employ today, but he’s curious enough about these increasingly sophisticated metrics and how they too will continue to evolve: “If one coach decides to do things this way, by eight o’clock the next night, 15 more will be doing the same.”

The NFL great Vince Lombardi famously treated all of his athletes the same — like dogs. Bowman, by contrast, looked for the best in each man. He and his teams had little choice but to adapt. His first NHL coaching job, for example, with the St. Louis Blues, followed the league’s 1967 expansion draft. He inherited a squad of role players, fringe minor-leaguers, and veterans left for dead. The roster included two future Hall of Famers, but also idiosyncratic athletes in their late thirties. Bowman accepted and accommodated their quirks with surprising success — perhaps best exemplified by the goaltending tandem of Glenn Hall and Jacques Plante. “You coach what you’ve got,” Dryden observes. And during the 1968 Stanley Cup semi-finals, what he had included a goaltender, Hall, complaining of vision problems. Players were told not to score on Hall during practice — and his complaints quickly dissipated. He went on to stop forty-four shots in a single night.

Toward the end of his coaching career, Bowman helped shift perceptions of European players, who were seen as indifferent to the Stanley Cup. By that point a coach with the Red Wings, he saw something else: unique qualities and winning results. He put five Russians on the ice — a novel move at the time — and they delivered. “They were the Detroit Red Wings,” Dryden writes, “not the Harlem Globetrotters.”

Bowman was equally committed to transforming his captain and star centre, Steve Yzerman, who had five seasons with more than fifty goals under his belt. Few coaches would have had the foresight or credibility to demand that such a successful offensive player reimagine his game, but Yzerman’s knee problems and the team’s changing composition made a blunt conversation necessary. Following the Red Wings’ 1994 playoff loss, Bowman met with Yzerman and demanded that he redefine his style of play. The conversation sparked a deeper commitment to winning from Yzerman. He killed penalties, won faceoffs, and set the tone for a team that would value two-way play more than individual results. While his scoring declined significantly, he would win three Stanley Cups, in 1997, 1998, and 2002.

Bowman forged success through evolution and adaptation. It’s his qualities as a leader, thinker, and coach that Dryden celebrates in this vivid collaboration between one of the game’s most cerebral players and its most successful coach. Dryden offers a fitting analysis of a man who never set out to create sound bites, who didn’t claim to shape the characters of men, who kept his head down and focused on where the game was moving. As we see several of today’s coaches clinging unsuccessfully to yesterday’s sensibilities, hockey fans could not be faulted for seeking more of the Bowman approach. He blended in, but he also excelled. And for a half century, he lived a hockey life like no other.

Jeff Costen worked for three cabinet ministers in Ontario’s most recent Liberal government.

Related Letters and Responses

@DaveRonald13 via Twitter